Jean Paulhan, Progress in Love on the Slow Side, Trans. by Christine Moneera Laennec and Michael Syrotinski, University of Nebraska Press, 1994.

read it at Google Books

Jean Paulhan (1884–1968) is renowned in France both for his unrivaled skill as an editor and for his own subtle yet incisive writings. Paulhan directed the Nouvelle RevueFrançaise for thirty years, helping to make it into the foremost literary journal of his generation. Many of the most celebrated French writers of the period—Artaud, Bataille, Blanchot, Caillois, Camus, Giono, and Ponge, to name only a few—owe their rise to literary prominence in large part to Paulhan's rare vision, insightful criticism, and unfailing support.Although best known for his theoretical writings of the 1940s and 1950s, Paulhan established his reputation as a writer with his short fictional tales, or récits, composed during or just after World War I. Many of them have the war as their backdrop and are autobiographical in origin, evoking Paulhan's time in Madagascar, his brush with death while suffering from pneumonia, and his awkward love life. More than the subject matter, it is the precise, restrained lyricism of the prose, and Paulhan's attentiveness to the quirks and subtle twists of language, that make these stories so remarkable for their time. This book contains a selection of five of the best-known récits: Progress in Love on the Slow Side, The Severe Recovery, The Crossed Bridge, Aytre Gets Out of the Habit, and Lalie. Maurice Blanchot's tribute to Paulhan, "The Ease of Dying," is also included.

In 1945 Paulhan received the Grand Prix de Litterature and in 1951 the Grand Prix de la Ville de Paris; he was elected to the Academie Française in 1965.

This slight but remarkable volume contains five short stories written by Paulhan (1884-1968), a celebrated French critic and essayist, between 1910 and 1917; a lucid introduction by Syrotinski; and a concluding essay by the proto-deconstructionist critic Blanchot that's so heavy-handed that Syrotinski feels compelled to prick at it: ``The reader might wonder, in following Blanchot's labyrinthine path through Paulhan's thought, whether he doesn't end up burdening the recits with a kind of philosophical gravity.'' That would be a shame, for these mostly autobiographical tales are so dreamy and fragile that any extraneous weight could cause them to crumble. The title story involves a young soldier away from home and the arduous process by which he courts three French women-the title being no exaggeration. ``The Severe Recovery'' is a disorienting firsthand account of the delirium of a young man who, like his wife and mistress, shares his name with a character in the first story-leading to the confused aura projected by the tale. ``The Crossed Bridge,'' the vaguest story in this highly elliptical collection, is about a man's dreams on three consecutive nights. Without exception, Paulhan's narrative stance is reserved and observant, even to the point of distortion. His language, brilliantly translated, is painstakingly precise, with the narrators often retracing their linguistic steps in order to clarify the exact nuances of their descriptions. The result is that the things and images being described are rendered nearly inane. Paulhan, judging from these astonishing tales, was decades ahead of his time: a fully formed postmodernist writing during the overtures of modernism. - Publishers Weekly

In 1945 Paulhan received the Grand Prix de Litterature and in 1951 the Grand Prix de la Ville de Paris; he was elected to the Academie Française in 1965.

This slight but remarkable volume contains five short stories written by Paulhan (1884-1968), a celebrated French critic and essayist, between 1910 and 1917; a lucid introduction by Syrotinski; and a concluding essay by the proto-deconstructionist critic Blanchot that's so heavy-handed that Syrotinski feels compelled to prick at it: ``The reader might wonder, in following Blanchot's labyrinthine path through Paulhan's thought, whether he doesn't end up burdening the recits with a kind of philosophical gravity.'' That would be a shame, for these mostly autobiographical tales are so dreamy and fragile that any extraneous weight could cause them to crumble. The title story involves a young soldier away from home and the arduous process by which he courts three French women-the title being no exaggeration. ``The Severe Recovery'' is a disorienting firsthand account of the delirium of a young man who, like his wife and mistress, shares his name with a character in the first story-leading to the confused aura projected by the tale. ``The Crossed Bridge,'' the vaguest story in this highly elliptical collection, is about a man's dreams on three consecutive nights. Without exception, Paulhan's narrative stance is reserved and observant, even to the point of distortion. His language, brilliantly translated, is painstakingly precise, with the narrators often retracing their linguistic steps in order to clarify the exact nuances of their descriptions. The result is that the things and images being described are rendered nearly inane. Paulhan, judging from these astonishing tales, was decades ahead of his time: a fully formed postmodernist writing during the overtures of modernism. - Publishers Weekly

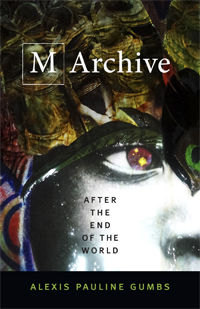

Jean Paulhan, U Catullus, Badlands Unlimited, 2011.

U are Catullus, a young poet who loves Lesbia and hates Cicero. Being who U are, U also enjoy drinking, going to parties, and cursing at the gods. This is the simple premise behind "U Catullus," Jean Paaulhan’s ingenious e-book. Based on the work of the scandalous Roman poet Catullus (87 B.C. - 57 B.C.), the reader is called upon to make decisions within the epic poem that lead to different storylines and outcomes. In lyrical poetic form, "U Catullus" unfolds like an ancient Roman version of TMZ, or a libertine novella for our interconnected age.

Jean Paulhan, The Flowers of Tarbes: or, Terror in Literature, Trans. by Michael Syrotinski,University of Illinois Press, 2006.

read it at Google Books

Les Fleurs de Tarbes, ou la terreur dans les lettres, first published as a single volume in 1941, was considered by Jean Paulhan to be the furthest-reaching expression of his thinking about literature and language. It is now recognized as a landmark text in the history of twentieth century literary criticism and in the emergence of contemporary literary theory. This is the first time it has been translated into English.

The playful tone and quirky, casual style of Paulhan's writing mask a theoretical intent and seriousness of purpose that are extraordinarily prescient. In The Flowers of Tarbes Paulhan probes the relationship between language, meaning, context, intention and action with unremitting tenacity, and in so doing produces a major treatise on the nature of the literary act, and a meditation on what we might now call the responsibility or ethical imperative of literature itself.

—

Uncanny how the stacks of books pile up, and I am swept around the point by tides and fail to beach at my intentions. Why is it that a note in Camus’s American Journals seems suddenly pertinent: “Naturally a man should fight. ‘But if he loves only that, what’s the use of fighting.’” (Accompany’d by vague sense—in tangled weekend revery—of fighting, gang-swift, echoing boots against cobblestones.) (How related to the noisy and wild hammer-swinging required to re-hang the gutter?) (And why the sudden inkling—just now—astride the bicycle, shooting through the empty intersection, that one ought to dump the daily half-ass’d squibs, and write only when compelled?) (“The compulsion is, precisely, the graphomania of the “daily half-ass’d squibs.”)

Trying to re-construct the reading of late (the littlest reading, sleep-interrupt’d, precanned, un-expanding). I keep pulling (as at a tap) at Robert Baldick’s Pages from the Goncourt Journal: how I love (for my sense of its terrible accuracy, for how it ought be apply’d to some of “our” notables, (“our” notaries, “our” notorious) criticules who make marvelous exceptions for any chair et os cohort, whilst remaining utterly blindfold’d by pre-disposed scurrility to some lumpen imaginary other, label’d for easy dismissal): “Sainte-Beuve is the Sainte-Beuve he has always been, a man forever influenced in his criticism by tiny trivialities, minor considerations, personal matters, and the pressure of opinion around him: a critic who has never delivered an independent, personal judgement on a single book.” Recall: it is Proust who writes Contre Sainte-Beuve, a man whose name sounds like the noise a cow makes. (Addendum: Paulhan, too, notes that “Sainte-Beuve attempted to classify writers’ minds; their works seemed inconsequential to him.”)

And, dabbling too, I approach Jean Paulhan’s 1941 The Flowers of Tarbes or, Terror in Literature (University of Illinois Press, 2006), translated by Michael Syrotinski. Isn’t it enough that he begins with an apparently made-up epigraph?

What Paulhan is concern’d with is the continual rut of language’s codification (he calls it Rhetoric). Opposed to that is “Terror,” a demand for continual novelty. Syrotinski:

(Again the need, reading Paulhan, to quote that thing out of Barthes’s Roland Barthes: “a Doxa (a popular opinion) is posited, intolerable; to free myself of it, I postulate a paradox; then this paradox turns bad, becomes a new concretion, itself becomes a new Doxa, and I must seek further for a new paradox . . .”) The only thing to do: keep the Janus-faced god that is literature turning (at high enough speed, the two faces merge into one). (That’s a kind of barmy mystical soft-shoe off the quibbling-stage, and resolves exactly nothing.) - isola-di-rifiuti.blogspot.com/2009/07/jean-paulhans-flowers-of-tarbes-or.html

![Image result for Jean Paulhan, Of Chaff and Wheat:]()

Jean Paulhan, Of Chaff and Wheat: Writers, War, and Treason, Trans. by Richard Rand, University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Reacting to widespread Nazi collaboration-both voluntary and otherwise-French patriotism surged in the wake of World War II. Resistance fighters were honored as heroes, collaborators were arrested, and the nation was bent on blurring its immediate past by expunging whatever was seen to have been pro-German. In this fevered context, a National Committee of Writers began to blacklist those who had saved their careers throughout the Nazi occupation. Jean Paulhan, who had supervised the literary arm of the French Resistance during the war and helped to found the National Committee of Writers, saw the dangers of its blacklist from the very outset: he denounced it in public, quit the Committee in protest, and then put his reputation on the line by printing the essays, anecdotes, and letters collected in this courageous book. Though perfectly able to conduct a polemic at white heat, Paulhan is chiefly concerned with putting a stop to the prosecution of writers, to restoring their critical freedom to write, publish, make mistakes, and to heal by moving forward honestly. He attacks friends, colleagues, and old associates who support the blacklist in the name of a patriotic democracy.

![Image result for Michael Syrotinski, Defying Gravity: Jean Paulhan's Interventions in]()

Michael Syrotinski, Defying Gravity: Jean Paulhan's Interventions in Twentieth-Century French Intellectual Historyread it at Google Books

“This book constitutes the first English-language book devoted to the work and influence of Jean Paulhan, and is written by someone who is remarkably familiar with his work. But, more importantly, it is the first one, no matter what language, to do full justice to the historical and intellectual implications of Paulhan’s work and to do it in light of contemporary Anglo-Saxon academic debates. One has been waiting for a major reassessment of the work of Paulhan. In this informative and intellectually challenging work, Syrotinski manages to promote this elusive, multifaceted, but central French literary figure as a key reference for deconstructionist and postcolonial debates.” ― Denis Hollier, Yale University

“This book is important as a study of one figure, Paulhan, whose texts have never been so brilliantly explored, and who was a central figure in French letters during an extremely interesting period of French history. It is also significant as a polemical contribution to current debates about the nature of literary studies: their relation to the study of history, to the encounter with non-Western cultures, to political and ethical issues, to gender questions.” ― Ann Smock, University of California, Berkeley

read it at Google Books

Les Fleurs de Tarbes, ou la terreur dans les lettres, first published as a single volume in 1941, was considered by Jean Paulhan to be the furthest-reaching expression of his thinking about literature and language. It is now recognized as a landmark text in the history of twentieth century literary criticism and in the emergence of contemporary literary theory. This is the first time it has been translated into English.

The playful tone and quirky, casual style of Paulhan's writing mask a theoretical intent and seriousness of purpose that are extraordinarily prescient. In The Flowers of Tarbes Paulhan probes the relationship between language, meaning, context, intention and action with unremitting tenacity, and in so doing produces a major treatise on the nature of the literary act, and a meditation on what we might now call the responsibility or ethical imperative of literature itself.

—

Uncanny how the stacks of books pile up, and I am swept around the point by tides and fail to beach at my intentions. Why is it that a note in Camus’s American Journals seems suddenly pertinent: “Naturally a man should fight. ‘But if he loves only that, what’s the use of fighting.’” (Accompany’d by vague sense—in tangled weekend revery—of fighting, gang-swift, echoing boots against cobblestones.) (How related to the noisy and wild hammer-swinging required to re-hang the gutter?) (And why the sudden inkling—just now—astride the bicycle, shooting through the empty intersection, that one ought to dump the daily half-ass’d squibs, and write only when compelled?) (“The compulsion is, precisely, the graphomania of the “daily half-ass’d squibs.”)

Trying to re-construct the reading of late (the littlest reading, sleep-interrupt’d, precanned, un-expanding). I keep pulling (as at a tap) at Robert Baldick’s Pages from the Goncourt Journal: how I love (for my sense of its terrible accuracy, for how it ought be apply’d to some of “our” notables, (“our” notaries, “our” notorious) criticules who make marvelous exceptions for any chair et os cohort, whilst remaining utterly blindfold’d by pre-disposed scurrility to some lumpen imaginary other, label’d for easy dismissal): “Sainte-Beuve is the Sainte-Beuve he has always been, a man forever influenced in his criticism by tiny trivialities, minor considerations, personal matters, and the pressure of opinion around him: a critic who has never delivered an independent, personal judgement on a single book.” Recall: it is Proust who writes Contre Sainte-Beuve, a man whose name sounds like the noise a cow makes. (Addendum: Paulhan, too, notes that “Sainte-Beuve attempted to classify writers’ minds; their works seemed inconsequential to him.”)

And, dabbling too, I approach Jean Paulhan’s 1941 The Flowers of Tarbes or, Terror in Literature (University of Illinois Press, 2006), translated by Michael Syrotinski. Isn’t it enough that he begins with an apparently made-up epigraph?

As I was about the repeat the words that this kind native woman taught, me, she shouted out: “Stop! Each one can only be used once . . .”(The Père Botzarro, along with “Alerte”—“for whom poetry seems so serious that he has taken the decision to stop writing it”—and “Innocent Fèvre” and “Juvignet” and some others, likely due to Paulhan’s “propensity for playful invention.”) The book is full of lines like “Aragon calls literature a machine that turns people into morons, and calls men of letters crabs.” Or: “Gourmont adds that a personal work quickly becomes obscure if it is a failure, banal if it is a success, and discouraging in any event.” (So gutting the flopping fish one’s land’d. “The banality of success surrounds us”—what Creeley might’ve admitted, had he the wherewithal.) Or: “Just as there is no revelation that literature is not expected to provide, so there is no contempt it does not also seem to deserve. And every young writer is astonished that anyone can stand to be a writer. Almost the only way we can manage to talk about novels, style, literature, or art is by using ruses, or new words, which do not yet seem offensive. . . . If it is true that criticism is the counterpart to the literary arts, and in a sense their conscience, we have to admit that literature these days does not have a clear conscience.”

—Botzarro’s Travel Journal, XV

What Paulhan is concern’d with is the continual rut of language’s codification (he calls it Rhetoric). Opposed to that is “Terror,” a demand for continual novelty. Syrotinski:

Terror . . . stands for a decisive turning point in French history, and more specifically in French literary history. This is described by Paulhan as a shift from the rule-bound imperatives of rhetoric and genre to the gradual abandonment of these rules in Romanticism and its successors, with the consequent search for greater originality of expression. This opposing imperative is what Paulhan terms Terror. Terrorist writers are those who demand continual invention and renewal, and denounce rhetoric’s codification of language, it tendency to stultify the spirit and impoverish human experience.(Suddenly the figure of “Alerte” seems less a stand-in for Rimbaud, more akin to Laura (Riding) Jackson, particularly the (Riding) Jackson of Rational Meaning: A New Foundation for the Definition of Words.“If one used words as possessed of their meanings so thoroughly that they had no existence except as meaning what they meant, one would have to—in the use of them—mean what they meant, have in mind to express what they expressed. Otherwise, one would be, while seemingly at one with the sense of one’s words, perpetrating a pretence with them, or, at best, putting oneself through an exercise in self-frustration.” So saith Schuyler B. Jackson in the (1967) “Epigraph” to that book.) What the refreshingly suspicious Paulhan notes (“I’m simply suspicious of a revolt, or a dispossession, which comes along so opportunely to get us out of trouble”) is precisely how illusory the seeming difference between Terror and Rhetoric is, how both the drive toward endless originality and the longings for a stable language end up, as Syrotinski notes, “enslaved to language,” Terror “trying to bypass it” and Rhetoric stuck with the canned expressiveness of cliché. Paulhan:

For Terror is above all dependent upon language in a general sense, in that it condemns a writer to say only what a certain state of language leaves him free to express: He is restricted to those areas of feeling and thought where language has not yet been overused. That is not all: No writer is more preoccupied with words than the one who at every point sets out to get rid of them, to get away from them, or to reinvent them.Terror-writing is blind to its own rhetorical status, blind to its limits as (one is tempt’d by one’s inner graduate student to say) always already codify’d language. (See FlarfCo®’s extremely limit’d “palette.” Examine briefly—it won’t require lengthy study—exactly what it condemns a writer to “express.”)

(Again the need, reading Paulhan, to quote that thing out of Barthes’s Roland Barthes: “a Doxa (a popular opinion) is posited, intolerable; to free myself of it, I postulate a paradox; then this paradox turns bad, becomes a new concretion, itself becomes a new Doxa, and I must seek further for a new paradox . . .”) The only thing to do: keep the Janus-faced god that is literature turning (at high enough speed, the two faces merge into one). (That’s a kind of barmy mystical soft-shoe off the quibbling-stage, and resolves exactly nothing.) - isola-di-rifiuti.blogspot.com/2009/07/jean-paulhans-flowers-of-tarbes-or.html

Jean Paulhan, Of Chaff and Wheat: Writers, War, and Treason, Trans. by Richard Rand, University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Reacting to widespread Nazi collaboration-both voluntary and otherwise-French patriotism surged in the wake of World War II. Resistance fighters were honored as heroes, collaborators were arrested, and the nation was bent on blurring its immediate past by expunging whatever was seen to have been pro-German. In this fevered context, a National Committee of Writers began to blacklist those who had saved their careers throughout the Nazi occupation. Jean Paulhan, who had supervised the literary arm of the French Resistance during the war and helped to found the National Committee of Writers, saw the dangers of its blacklist from the very outset: he denounced it in public, quit the Committee in protest, and then put his reputation on the line by printing the essays, anecdotes, and letters collected in this courageous book. Though perfectly able to conduct a polemic at white heat, Paulhan is chiefly concerned with putting a stop to the prosecution of writers, to restoring their critical freedom to write, publish, make mistakes, and to heal by moving forward honestly. He attacks friends, colleagues, and old associates who support the blacklist in the name of a patriotic democracy.

Michael Syrotinski, Defying Gravity: Jean Paulhan's Interventions in Twentieth-Century French Intellectual Historyread it at Google Books

“This book constitutes the first English-language book devoted to the work and influence of Jean Paulhan, and is written by someone who is remarkably familiar with his work. But, more importantly, it is the first one, no matter what language, to do full justice to the historical and intellectual implications of Paulhan’s work and to do it in light of contemporary Anglo-Saxon academic debates. One has been waiting for a major reassessment of the work of Paulhan. In this informative and intellectually challenging work, Syrotinski manages to promote this elusive, multifaceted, but central French literary figure as a key reference for deconstructionist and postcolonial debates.” ― Denis Hollier, Yale University

“This book is important as a study of one figure, Paulhan, whose texts have never been so brilliantly explored, and who was a central figure in French letters during an extremely interesting period of French history. It is also significant as a polemical contribution to current debates about the nature of literary studies: their relation to the study of history, to the encounter with non-Western cultures, to political and ethical issues, to gender questions.” ― Ann Smock, University of California, Berkeley