"Heriberto Yepez is one of the most active and protean writers of his generation."—

Review: Literature and Arts of the Americas

"A forceful antipoet, a technician of the boundaries."—

Los Angeles Review of Books

Famous for picking fights with a range of writers, both living and dead, Tijuana author Heriberto Yépez is in full provocateur-mode in this collection of work written in English over the last fifteen years. An explosive, genre-bending Molotov cocktail of poetic critique.

Yépez is at the forefront of a generation of writers who are questioning notions of fluidity and synthesis, a generation that has seen those same categories veil the advent of global neoliberalism…

Yépez is a forceful antipoet, a technician of the boundaries, a split-form borderzone nagualist

.- EDGAR GARCIA more herewickedly irreverent —

RODRIGO TOSCANOHis litanies of despair and the depths of human misery provide an ominous view of Tijuana at crisis point. —JASON WEISS

About Me: In EnglishI am possessed by the most powerful

Revolutionary force in the world today:

The Anti-American spirit.

But I am written and I write in English

I too sing America’s shit.

I am inhabited by imperial feelings

Which arise in my mind as images

Of pre-industrial rivers

Or take some technocratic screen-form.

My hopes are these wounds

Are also weapons. But they may be undead

Scholarly jargon.

I am colonized. I dream of decolonizing

Myself and others. The images of the dream

Do not match up. I am the body

And the archive.

A bomb is ticking in my old soul.

And the life of the bomb

Trembles in the hands of my new voice.

I am a professor in the Third World.

What do I know? Libraries in the North

Do not open their doors. I laugh at myself

Imagining what the newer books state.

Writing is counter

-insurgent. But the counter

-insurgency

Leaders want our body

Believing writing is freedom.

This is as far as my English goes.

![Image result for Heriberto Yépez, The Empire of Neomemory,]() Heriberto Yépez, The Empire of Neomemory, Trans. by Jen Hofer, Christian Nagler, and Brian Whitener, Chain Links, 2013.download it here

Heriberto Yépez, The Empire of Neomemory, Trans. by Jen Hofer, Christian Nagler, and Brian Whitener, Chain Links, 2013.download it hereIn 1951, Charles Olson set out to spend some time in Mexico. He was only there for five months and he didn't learn much, but this time in Mexico would come to define all the poetry he was yet to write. Yepez begins with Olson in Mexico, with the possibility that he might be writing a study of Olson, a study of Olson's Mexico-philia. But what he writes instead is a breathtaking investigation of the relation between USAmerican poetry and Empire that careens idiosyncratically through the great men of empire--not just Olson, but those many other men who also traveled to Mexico, such as William Burroughs, Antonin Artaud, D. H. Lawrence, Herman Melville, and Ray Bradbury. This work is a dismantling of Olson, and of empire, and yet it is also clearly an inside job, a book that could only be written by someone who had spent hours thinking with and through--and beyond--Olson.

excerpt:There are Laws: Taking Down the Pantopia

“There are laws,” begins Olson’s essay “Human Universe” written in Mexico. How does one create the illusion that there are general laws? The foundation of time reduced to space is, precisely, the supposition that there exist laws that function in the same way (homogeneously) across all (heterogeneous) times. If different times are united by the same laws, then, these times are not separated and thus form a single space.

This belief is the basis of totalitarian thought, in all its forms. Television fabricates images—and society fabricates images for television—and the spectacular relations between these fragments produce the fallacy of a commonly held reality: the space of a “nation,” a “territory,” an “epoch.” The takeover of the center of Oaxaca by striking teachers, the flooding in Ciudad Juarez, and civil resistance in Mexico City, in co-existence with the war between Libya and Israel, the state of maximum alert in the United States and England—these events are represented in discourse and the news as symptoms of the same phenomenon, as events related to each other. The pantopia has penetrated deeply into our semi-consciousness and is situated at the border between the unconscious and conscious, in such a way that it permeates, in both directions, human thought. It is thus the Interzone or semi-consciousness that has become the key site in our present-day psyche. Pantopia seems so “natural” to us that doubting that its events are related and even considering that each event might obey its own laws in the space-time in which it is realized, as distinct from other space-times, can only appear a strange or at least very unusual idea.

more here[NOTE. Over he last two decades Heriberto Yépez has emerged as a new & provocative voice in Mexican letters & as a thinker about writing, art & performance, & a range of literary, philosophical and social issues. Over that same span he has published in a wide variety of genres – fiction, poetry, essays, translation, criticism, & theory, & has proven to be a controversial literary artist & critic in Mexico, while the range of his critical interests covers both Latin American & North American issues, extending into works of experimental & political interest on both sides of the border & beyond. His innovative writing & his critical essays have won him – at latest count – some fourteen awards in Mexico, including four national literary awards over the last decade, & he has received increasing recognition among experimental & younger writers in the United States. With all of this in mind the distinguished Mexican critic Evodio Escalante has written that “there is no question that Heriberto Yépez is one of the most powerful literary intelligences now active in our country.”

The Empire of Neomemory begins as a sometimes harsh critique of Olson’s experience of Mexico but expands into what the Chain editors describe as “a breathtaking investigation of the relation between USAmerican poetry and Empire that careens idiosyncratically through the great men of empire—not just Olson, but those many other men who also traveled to Mexico, such as William Burroughs, Antonin Artaud, D. H. Lawrence, Herman Melville, and Ray Bradbury.” Writes Yépez himself in summary: “Olson is part of the American dream, the dream of expansionism in all its variants. It is with the purpose of understanding this empire that I have written this book. Olson in and of himself does not interest me; I am interested in his character as a microanalogy for decoding the psychopoetics of Empire. Philosophy tries to comprehend reality through a discussion of abstract concepts produced by floating masculine heads (decapitalisms); in contrast, what I want to understand is the present via concrete bodies, historical microanalysis via the hunt for biosymbols. Using the text, I want to see through it to glimpse the substructure and the superstructure.” And the

Chain editors again: “This work is a dismantling of Olson, and of empire, and yet it is also clearly an inside job, a book that could only be written by someone who had spent hours thinking with and through—and beyond—Olson.” (J.R.)] -

jacket2.org/commentary/heriberto-y%C3%A9pez-empire-neomemoryThere's an interesting back-and-forth going on at

Jacket2 at the moment regarding Heriberto Yépez's ChainLinks book,

The Empire of Neomemory, published in Spanish in 2007 and recently translated by by

Jen Hofer, Christian Nagler, and Brian Whitener for this edition. Yépez--called "one of the best writers and chroniclers of contemporary Mexico and one of the two most important literary minds writing in Mexico right now"--set out originally to investigate

Charles Olson's time in Mexico, but eventually wrote of his project: "Olson in and of himself does not interest me; I am interested in his character as a microanalogy for decoding the psychopoetics of Empire."

In the spring,

Jerome Rothenberg posted excerpts from the book on his

Jacket2 Commentary page, which drew attention from a member of Il Gruppo, Benjamin Hollander, who now responds to Yépez's suggestion (as Hollander puts it) that "Olson and his poetry and prose reflect the impulses of a totalitarian and imperialist servant of empire." Hollander writes: "But now, inexplicably, fantastically, [Olson] has been morphed into the imperialist emissary of empire. Why has this happened?" More:

Members of Il Gruppo (Amiri Baraka, Jack Hirschman, Ammiel Alcalay, Carlos b. Carlos Suarès, Benjamin Hollander, and others) intend to respond in a place and form where such a debate — usually sublimated into one or another mode of theoretical double-speak, political correctness, or “fair and balanced” flattening of positions — might actually be forced out into the open. We will point to commentaries diametrically opposed to Yépez’s claims about Olson. For example, we would point to Diane di Prima’s lecture on Olson in which she recalls asking Olson

“When did America go bad? Was it after Jefferson? Was it late as Andrew Jackson and the stuff with a national bank?” Charles answered me instantly. Conspiratorially. Leaning close to my ear, he half-whispered in that gruff voice he used when he particularly wanted to underscore what he was saying: Rotten from the very beginning. Constitution written by a bunch of gangsters to exploit a continent.

Or we would point to comments by Olson’s Japanese translator, Yorio Hirano, who writes that Olson’s

Maximus Poems is a book of quest. Maximus, who wishes to find innocence in the beginning of America, finds the fact that the beginning has already been contaminated by the filth of commercialism and nascent capitalism brought there by Pilgrim Fathers.

As with any response to a revisionist historian’s subject, it is not so much the subject — in this case, Olson — which needs to be defended: his poetry and the facts of his life will do just fine in speaking for themselves. This is why it is difficult for Il Gruppo to buy into defending Olson as if we were presenting just another perspective in order to have a fair and balanced counter to Yépez’s so-called history. This move would mock the facts of Olson’s life. Are astronomers in the name of “fairness and balance” asked to present “the other side” to those who believe the moon is made of green cheese?

Rather, Il Gruppo intends to directly address Yépez’s claims, most importantly why they are being made, why and by whom they are seriously being entertained, their purported basis, and how they fall into a pattern of attacks on Olson. The space and form where such issues will be forced into the open is still under discussion.

We're looking for more information on Il Gruppo in general, and are keen to see them really wrestle with this work and literary history. Rumors circulate that they're looking to publish a small book on the matter. We'll keep you posted. -

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet/2013/09/il-gruppo-surfaces-to-respond-to-heriberto-yepezs-complicated-book-on-charles-olsons-time-in-mexicoUp until a few years ago, I’d only read bits of

Charles Olson’s writing, but I’d never really fallen for him. He’d always been one of those dead white men who I knew was important, a classic with whom I thought I

should spend time. Since I first fell in love with James Baldwin as a teen or Gloria Anzaldúa as a college student, something about these older, straight, white male writers just didn’t register for me. I couldn’t get access to them, and they felt removed, irrevocably of the past. And yet in the last few years, I’ve come back around to a number of them, now including Olson. To spend time with him, and his lifelong projective poetic project based in and around Gloucester, Massachusetts.

El imperio de la neomemoria by Heriberto Yépez brought me back to Olson: first when it came out in 2007 in Spanish from Almadía, an indie press based in Oaxaca, México. Yépez—a writer from the border city of Tijuana—has a long list of books published in Spanish that includes poetry, fiction and critical prose, as well as a a few books of experimental poetry in English. I’ve read Yépez for years, but recently I’ve had the pleasure of (re)reading him in English, as

The Empire of Neomemory has been released in English from

ChainLinks: the result of a careful, painstaking translation by Jen Hofer, Christian Nagler, Brian Whitener (and partially by Yépez himself as a vital conversant for the translation project.)

![El Imperio de la neomemoria]()

Yépez’s book made me want to delve deeper into Olson’s

magnum opus, TheMaximus Poems; he made the book feel incredibly relevant. In his book, Yépez pulls Olson off his pedestal, making his poetics and his mission more human, no longer the project of some god on the literary hill. In

The Empire of Neomemory, Olson becomes a young, fallible striver, a man-boy who wants more and more and sometimes in a wheedling kind of way. He’s not powerful or mighty; he’s a bit base, a little prone to overstatement, needy and defensive. Yépez psychoanalyzes Olson, investigating his Oedipal complex and his relationship with his father, thus bringing him back down to earth. Like any complicated, prickly personality, his vulnerability made me want to get to know him better.

Yépez also concentrates much of his analysis on Olson’s travels in Mexico, his search for Mayan authenticity and Quetzalcóatl, the plumed serpant god of the Aztec. Yépez argues that, unlike Pound, Olson wants to let in “the indigenous and the oral contemporary.” It is an investigation into what Yépez calls variously the “co-Oxident” and “kinh time,” “pantopia” and “neomemory.” As a USAmerican* who has spent a lot of time in Mexico, I’m obsessed with the transnational relationships between our two countries; I’ve been fascinated with Yépez’s critique of Olson’s relationship with Mexico, stealing from the country while simultaneously rejecting and undervaluing it and its people, this complicated brew of rejection, prejudice and longing for the Other.

In all of Yépez’s writing, he is always contradictory and complicated, yet also wont to use grand, polemical statements. It’s a strange mix, often uncomfortable and frustrating, yet revelatory and stimulating at his best. As usual, Yépez delights in hyperbole in this book: “What Romanticism was for Modernity, the 50s will be for the North American Empire. And they will be its Middle Ages—its Middle Ages express,

fast food classics!” and “Fascism is remix.” He’s a master of the pointed turn of phrase.

In

The Empire of Neomemory (as opposed to some of his other, older critical work), Yépez achieves a writing that multiplicates and renegotiates its own relationship with itself. At every turn, it appears to be a critical text that doesn’t want to be

just criticism or critique, but something different, something bigger. This book starts off as a biographical exploration of Charles Olson, his life in Gloucester, his biography and his work, but it is also effort to grapple with imperialist logic itself. As Yépez says, “Olson in and of himself does not interest me; I am interested in his character as a microanalogy for decoding the psychopoetics of Empire.”

What Yépez posits is: an indictment of an imperial sense of time that converts itself into space, into landscape. An indictment of the self as the foundation for conceptions of that time. A series of postulations that desnap. Desnapping. An evisceration of the idea of remixing and appropriation and fragmentation as resistant poetics. Yépez wants us, as experimental readers and writers, to think more deeply about our own complicity and our incapacity to free ourselves from a damaging loop of colonialism and empire. He uses grand, polemical statements to force us to rethink the grand, polemical statement. Yépez (and experimental writing more generally) incarnates the very contradictions he sets out to untangle.

And for Yépez, the roots of these contradictions can be traced back to Olson, not as the foundational moment, but rather as a particularly transparent distillation of the links between imperialism and USAmerican avant-garde poetics. If we go back to Olson’s ideas on Projective Verse, perhaps his most well known poetic statement: “ONE PERCEPTION MUST IMMEDIATELY AND DIRECTLY LEAD TO A FURTHER PERCEPTION. It means exactly what it says, is a matter of, at all points (even, I should say, of our management of daily reality as of the daily work) get on with it, keep moving, keep in, speed, the nerves, their speed, the perceptions, theirs, the acts, the split second acts, the whole business, keep it moving as fast as you can, citizen. And if you also set up as a poet, USE USE USE the process at all points, in any given poem always, always one perception must must must MOVE, INSTANTER, ON ANOTHER!”

In this quote, we see how Olson’s sense of speed (and time) becomes spatial. It’s interesting that he makes this poetic “call to arms” at this particular moment in 1950. 1950 being the year that the Cold War (and the nuclear arms race) begins to gather steam as Truman orders the development of the hydrogen bomb. Also the year that the Korean War begins as North Korean troops march South. Olson lauds a poetics based on the “projectile” and the “percussive” just as bombs begin to drop on the Korean peninsula. As Yépez points out, these terms and others like “prospective” are instantly and inherantly suspicious, linked to Cold War politics.

As I worked on this short essay, I listened to

recordings of Charles Olson and a

2010 Poem Talk on

Pennsound with Charles Bernstein, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, and Bob Perelman. As the best of the Poem Talks do, this discussion helped me to think about how Olson is regarded within the world of contemporary, experimental USAmerican poetics. I love the coversation and I am happy it is online, yet it also reminded me why I have often kept my distance from poets like Charles Olson; each one of the interlocutors mentioned a field of references that often felt foreign or overly expansive; the depth of their knowledge made Olson seem unapproachable and difficult, the realm of those with advanced degrees and books already written on the subject. For example, Bernstein refers to his first books on Olson and his thinking

then as opposed to his thinking

now. There is a sense of the history of thinking about Olson, his importance within the field that makes me hesitate to opine.

And yet, the discussion was also helpful to think about how Yépez’s project is so necessary at this particular moment. Bob Perelman says, “I’d love to desacralize our heroes. Olson is a heroic figure. Sacralization is always a problem: a

lessoning as opposed to a

lesson.” Perelman helped me to understand one of the joys of Yépez’s project: he pulls Olson out of the stratosphere, he trounces him, psychoanalyzes him and sends him off on a sad, lonely trip to the Yucatán, putting him on a grimy, fallible level. Like the kids say, he becomes

relatable. Rachel Blau du Plessis talks about how Olson’s epistolary poems in

Maximus link zones: the body, the city, the world-historical, and she argues that there are no impediments to the linking of those zones. She notes that while Olson clearly pursues a mission connected to ideas of rootedness, place and geography, he also falls for the tropes of American exceptionalism and westward conquest, and yet she limits herself, saying: “I don’t want to be too reductive.” Yépez is not scared to be seen as reductive; polemicism is at the core of this project.

I also think Yépez undercuts analyses of Olson that would posit him as a counter-hegemonic hero. For example, in the Poem Talk, Al Filreas sees Olson as arguing against American mercantilism. Charles Bernstein sees Olson arguing that we are not beholden to the past and to tradition, that it does not define us entirely, though our words come from that past. Quoting Olson “I no longer am, yet am, / the slow westward motion.” Bernstein argues that we need Olson, that we need his assertion that: “An American / is a complex of occasions, / themselves a geometry / of spatial nature.” He sees this line as an argument against USAmerican fundamentalisms, a radical attack and critique on the idea of an American as one thing or an essential Americanness.

Yépez’s

Empire takes apart this counter-hegemonic grandeur, not only of Olson but of USAmerican literary experimentalism more generally. It forces us to recognize the Olson in all of “us,” even to question that very “us.” Olson pushes for a radical new poetics and at the same time embodies empire in a new appropriative, totalizing poetics of the new. As Yépez says, “[Olson’s] U.S. readers flagrantly ignore the relationship between USAmerican canonical writing and imperialism, a reflex typical of USAmerican hegemonical intellectuals, but in this case one that includes the USAmerican experimental literary left, in need of a radical re-reading of the ideological foundations of its current poetics.”

Yépez continues: “From the work of Olson to the parody (a la Woody Allen) that Charles Bernstein makes of “projective verse,” from the investigative poetry of Ed Sanders constructed with monads of information to the

cut ups of Burroughs that sampler of the body-of-reorgans, from the “plagiarisms” of Kathy Acker and her intense prose made of blocks to the techniques of the post-Language poets, USAmerican poetry, in its dream of a

symposium of the Whole, as in the “new sentence,” has been a critical poetry, a pantopic poetry, based in

displacement and parataxis, based in neomemory.” But this indictment is not just for the U.S. experimental poets, but it extends out to critique everyone, everyone whose culture is based on memory. All of us are conservative, Yépez argues, and he includes himself.

At the

end of the ChainLinks volume, there is a fascinating translators’ note written in the first-person plural, a “we” that includes the three translators and Yépez. The note does amazing work thinking through the perils of translation at this particular historical moment, delving into the complicated array of issues that emerge out of attempting to translate this resolutely anti-imperial book into the imperial tongue that it is rallying to undermine. The translators also remind the reader to continue to resist (and riot) and yet to also “allow the moment of complicity back in again and again” as

Empire of Neomemory does so often: “what I have said of Charles Olson is the method by which I recognize myself.”

As I think most experimental writers would, I found myself identifying and dis-identifying with Yépez’s critique of Charles Olson throughout the text. Moments where I felt my own work and my own aims as a writer were made manifest and then shred to pieces. Moments when Yépez seemed to be tearing into my own practice as a writer. And I think this is an incredible gift (if we want to talk about poetry or criticism as gift).

In the book, Yépez attacks the concept of the post-anything, positing it as another progress-oriented mistake that recreates a linear, spatial sense of time. As he says, “the idea of the

post attempts to persuade us that there has been a confrontation, a collision of forces, in which either a parricide or overcoming occurred, a moving beyond this conflict, a resolution or a passage to another site.”

The book is not saying that there is another world beyond this one, a better way of doing things (for which Yépez could become the master). Rather, it embodies the complicities and failures of experimental literature, while pushing the reader (especially the USAmerican reader) to recognize her own inextricability from these webs. Perhaps, the book signals, it is time to think about forgetting the grand, totalizing dream of neomemory.

* Thanks to Jen Hofer for working to popularize this term USAmerican, which so clearly resists the erroneous definition of America as the U.S. of A. -

John Pluecker http://outwardfromnothingness.com/how-could-we-forget-thinking-about-heriberto-yepezs-the-empire-of-neomemory/On September 16, 2014, “post-Mexican” writer, critic, psychotherapist, and literary provocateur Heriberto Yépez announced to the world that, after twenty years of work on his “writing project,” “it can be said that Heriberto Yépez’s oeuvre has concluded” and that the “young man” who was Heriberto Yépez has “gone” forever. Such a grand gesture may seem self-indulgent posturing if viewed from the US side of the

frontera, the borderlands between the US and Mexico, where Yépez’s work is not widely known. Yet

al otro lado, in his native Mexico—he was born in Tijuana in 1974—Yépez has established his reputation with an extensive and varied body of work that is impressive given his young age. Yépez has won several important national awards and, according to literary critic Evodio Escalante, he is one of “the two most powerful literary intellects” currently active in Mexico. The late celebrated poet and journalist Daniel Sada considered him “the most assured of [Sada’s] literary critics” and praised Yépez’s novel

Al Otro Lado for being “the best in that genre called ‘narco literature.’” Over the course of his two-decade long “writing project,” Yépez has employed his art to transgress the artificial boundaries erected by what he and his translators term the “USAmerican Empire” that imposes its own version of reality on those individuals who have had the misfortune to be living in the sphere of its American Dream, which, according to the writer, is “the dream of expansionism in all its variants.”

Like Tijuana, the border town that shaped his consciousness, Yépez—his work and identity—resists being pinned down, especially by USAmerican narratives about race, culture and language. His extensive bibliography embraces a wide range of genres and disciplines—from experimental novels and poetry to cultural and literary criticism and translations, written in both Spanish and English or a mixture of both. Yépez also frequently collaborates with scholars and writers in Mexico and the US, forging new connections that defy boundaries fixed by external authority. Independent multicultural collaborations like these can do much to subvert the myopic worldview that, when it comes to culture, Mexico is the poor stepchild to the US’s Big Daddy and the western tradition. As Yépez’s criticism of US cultural imperialism rightly reveals, any true appraisal of the record must account for, as Yépez puts it, the droning “homochrony” of the American Dream and its towering fortress of forgetting.

Yépez’s ambition to expose the fortress’s “substructure and superstructure” sounds laudable in theory. Yet when it comes down to reading Yépez in practice, one feels that, in trying to right the record, he has fallen prey to the very same fallacy of which he accuses USAmerica—reducing a complex relationship to that of unequals—which again fails to do justice to either nation’s cultural tradition or the historical record.

Yépez’s ambition to liberate Mexico from USAmerican imperialism is especially evident in the critical work

The Empire of Neomemory for which Yépez was awarded the prestigious Premio Nacional de Ensayo “Carlos Echánove Trujillo.” Ostensibly,

Neomemory serves as Yépez’s exploration of poet Charles Olson’s 1951 trip to Lerma, Mexico, and the significant impact this journey to Mexico had on Olson’s career. Yet the study, first published in 2007 and translated into English in 2013, serves less as conventional literary study and more as the chronicle of Yépez’s quest to rescue Mexico’s rich cultural heritage from agents of the “Oxident” (a neologism which, we are told by the volume’s translators, signifies “a combination of Occidental and oxidized”) who have hijacked it. According to Yépez, many of the great figures of the modern and postmodern Western literary traditions may be counted among their numbers. In fact, Yépez emphasizes that

Neomemory is not to be taken as a traditional critical study of Olson and Mexico within the context of American postmodernism, but as a “dismantling” of the poet and, by extension, the Empire he served. As Yépez writes, “Olson in and of himself does not interest me”; instead, he employs the book as a blade to cut the poet—who, at 6’8” was literally a giant of a man—down to size. To borrow Yépez’s own pun,

Neomemory is his

decapitalism of Empire’s “decapitalisms,” a 250-page beheading of Olson, one of the biggest “floating masculine heads” in the USAmerican literary pantheon. Whether Yépez’s guillotine is as sharp as his ambitions is another issue altogether.

There is no doubt that

Neomemory is a daring work on many levels; as Yépez, according to the editors, “careens idiosyncratically” through time and space, he showcases his erudition through dazzling flights of free association, neologisms and puns woven into the fabric of his criticism. He begins by “Going Postal,” the pop-culture term for “rampaging violently”: Yépez creates riffs on all things postal to frame his psychoanalytic investigation of Olson’s childhood in the house of Karl, Olson’s alcoholic postman father, and Mary, a religious Catholic. According to Yépez, Olson’s family life in Gloucester was marked by discord and distance. Olson grew up among “phantoms,” living in the shadow of his failed Big Daddy Karl Joseph who projected all his hopes and aspirations on his young son after he’d been fired from his position at the post office. Like a modern Bartleby, Olson refused to show up to work after his bosses vindictively canceled his leave to take Charles to the three-hundredth anniversary of the Pilgrims’ landing at Plymouth Rock because of the elder Olson’s efforts to organize his fellow postal workers; and in the “abyss” Mother Mary “sowed” by teaching her son to loathe his body and love only ideas. Cut off from the “co-body,” from feminine intimacy, Yépez’s Olson finds he can only connect to the world through letters, the artifacts of patriarchy, like “a wounded Hermes” whose existence boils down “to remittance and postal hope.” According to Yépez, Olson expresses and receives his “best ideas” through the mail (or, should I say

male, although the pun only works in English), making the poet the empire’s “desperate mailbox.” From this portrait, it’s no wonder that Olson felt more comfortable communing with dead Sumerians, Ancient Greeks, and Ancient Mayans, whose tongues had been metaphorically torn out by the zealous Catholic priest centuries past, than with living breathing humans.

And so, in

Neomemory, Yépez leads us from Olson’s Freudian nightmare of a childhood, through the critic’s encounters with Melville, Pound, Rimbaud, Borges, and the other dramatis personae of western modernism and postmodernism. Then he arrives at his destination, Lerma, Mexico, where Olson, the self-professed “archeologist of morning,” had journeyed on his private expedition to decode the Mayan hieroglyphs. Yet, according to Yépez, Olson was not, in fact, acting on his own accord; he casts Olson almost as if he were an antagonist in a Graham Greene novel, an agent in the service of USAmerica complicit in the Empire’s co-opting of Mexico’s cultural memory. This dark portrait also resonates with the handiwork of Friar Diego de Landa Calderón, bishop of the Yucatán, who had immolated the Mayan record after the Spanish conquest, leaving the world a record of fragments with incomprehensible glyphs.

Yet by the book’s end, it doesn’t really feel like Yépez has made new incursions across the border to conquer those he accuses of being conquerors. One major weakness is that for Yépez to succeed he must discredit Olson the man to elevate his own prestige as a critic. After all, Yépez frankly admits that

Neomemory isn’t about Olson at all; it’s about Yépez attempting to decapitate Olson, whom he considers to be, at least in the field of literature, USAmerica’s primary agent in the cultural co-opting of Mexico. However, for the final execution to work, Yépez must convince us that

Olson represents all of what there is in each one of us in the Co-Oxident, all of what is there and, at the same time, all of what cannot be in us of this Whole, which is in itself impossible. All of us are Olson. Each one of us constitutes an avatar of the United States.And “Olson’s tracks . . . lead us to the avatars of empire.” Everything in his analysis hinges on this inflated portrait of Olson, even when he himself admits that no man “can really represent an entire culture.” But Olson’s been dead since 1970. Just three years after his death, critic Marjorie Perloff, in her “Charles Olson and the Inferior Predecessors: ‘Projective Verse’ Revisited,” argued that for all Olson’s pretentions about originality, his acclaimed essay was “essentially a scissors-and-paste job, a clever but confused collage made up of bits and pieces of Pound, Fenollosa, Gaudier-Brzeska, Williams and Creeley.” Even during his lifetime, not everyone was on the Olson bandwagon. In his review of “Projective Verse,” poet Thom Gunn wrote that the writing in the essay “was the worst prose since Democratic Vistas.” Yépez’s portrait of Olson as some USAmerican conquistador rings hollow based on these inflated claims. It’s as if Yépez believes that if he blows enough theoretical hot air into Olson’s effigy, the long-dead writer will be grand enough to become the lead float in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade—a big target and, thus, easy to shoot down. But given too much air, the balloon will burst. Olson was a giant of a man, but his life in death reads like the dust on Ozymandias.

After reading

The Empire of Neomemory, sadly, I’m not sure I’ve learned much about Olson, the impact his trip to Mexico had on his development as a writer, or the contradictions inherent in the US’s appropriation of Mexico’s cultural heritage. And that’s a shame. I kept wanting more than all the abstract talk about bodies, time, space and imperial amnesia. Yépez’s neologisms, the lingua franca of his criticism—with hyphens and

cos,

neos,

metas,

bios,

geos and

posts tacked on in front—feel like the fossilized tropes of the Freudian and post-colonial lit crit of some thirty years ago. As a result, the reader often stumbles over the self-conscious prose, as is the case in one particularly impenetrable passage in “Moses of the Yucatán”:

Unfaithful, erotically split, divided, labyrinthized by his mythomania, fantasizing vacillating between his totemic petriotic loyalty of the United States and his compulsion toward a knowledge of the clandestine cultures of the world, ubiquitous, bifurcated, deformed out of pure interbelittled disfragments, polyphonic excisions, and Janusian self-throat-slittings, Olson desperately hunted down a principle that might unite it all.How to make it all cohere. How to build a co-here where everything existing is united. Olson’s “will to cohere” has only been understood in the dimension of coherence, of Apollonian integration: that is, of logic, of meta-recounting of atypical junctures, yet not in its dimension as a site, as pantopia as co-space, co-here or co-where.One might argue the fault lies with the translators, but they collaborated closely with Yépez and provide scrupulous evidence in the form of footnotes that they have remained as faithful as possible to his voice. Yet paradoxically, the fault does, essentially, lie in translation—that is, a portrait of Olson cherry-picked to suit the critic’s teleological purposes and his attempts at channeling Olson’s mercurial style. To carry out his analysis, Yépez must distance himself from the very thing that makes the late poet, in my view, so original, memorable and worth writing about: the flesh and blood human being, filled with contradictions, who searched for new means of expression in the post-war world where “man [had been] reduced to so much fat for soap, superphosphate for soil, fillings and shoes for sale.” Olson resisted the consumer world and its end-stopped poets. Still, Yépez is right. Olson was no archeologist; yet he wasn’t much of a conqueror either. After spending less than a year in Mexico, Olson threw in the shovel. The locals and the official archeologists annoyed him. They got in the way of his dream of finding the Mayan Rosetta Stone. Olson the archeologist, like Yépez the writer, had moved on. While Yépez vanishes into No-Man’s Land between frontiers, after Lerma, Olson returns to his native land. The prodigal son goes back to his roots: his post-office father, the sailors, Ishmael and Gloucester, the whaling village and the Sea that had so informed his artistic vision. For twenty years until his own death, Olson, the poet-sexton, worked feverishly excavating the dead in Dogtown’s graveyard, Maximus’s voice scrimshawing exquisite poems on their forgotten bones. Ironically, many of the joys in

Neomemory are in Yépez making us want to return to Olson and his genius, which are precisely what he would like us to forget. -

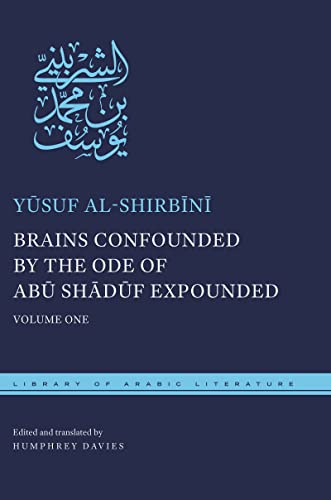

Deborah Garfinklehttps://www.kenyonreview.org/kr-online-issue/2015-fall/selections/the-empire-of-neomemory-by-heriberto-yepez-738439/The Empire Of Neomemory By Heriberto Yepez - Dark-devThe Empire Of Neomemory By Heriberto Yepez - Pardon-mamanJose-Luis Moctezuma on Heriberto Yepez - Chicago Review![Image result for Heriberto Yépez, Wars. Threesomes. Drafts. & Mothersm,]() Heriberto Yépez, Wars. Threesomes. Drafts. & Mothersm, Factory School, 2007.

Heriberto Yépez, Wars. Threesomes. Drafts. & Mothersm, Factory School, 2007. WARS. THREESOMES. DRAFTS. & MOTHERS, by Heriberto Yépez, plays with September 11th. It's a book on war. A book of hate toward the United States. A book of love toward ghosts. Several stories are triggered around the war against Iraq, among them the story of a couple of brothers involved in several love triangles. This is a love-drug-passion-esquizophrenic experiment that involves you till the end. This is a book made of orgasms and quotes. This is a book on writing in the age of Empire. This is a book on the deep meaning of 'United-States'.

Heriberto Yépez, a Tijuana writer and Gestalt psychotherapist who has been showing up in the US scene a lot during the last few years, writes so as to push buttons. I remember hearing him read a few years ago at a small liberal arts college. He read a piece that had a man fucking a pregnant woman and the fetus, his son, giving the man a blow job as he did it. I remember squirming as I listened with feminist anxiety to Yépez read this. At the end of the story, it became clear that the man is George Bush and the fetus is George W. Bush and I had that ah ha moment where I realized that my desire for gender decorum had me protecting all sorts of imperial male lineages. Or another story: at UCSC a few years ago Yépez gave a paper in which he claimed “I am Bush” and then, moving from “I” to “we,” he said “Bush is our way to hide we are Bush” (this talk is posted at

mexperimental.blogspot.com). If these examples are not enough to prove his provocations, then check out his video “Voice Exchange Rates” (available on youtube) where he has a cartoon image of Gertrude Stein with a swastika carved into her forehead Charles Manson style asking “why do Americans rule the world?”

The Bush as fetus reading really pointed out to me how distinctive Yépez’s work is. It manages to hide provocatively conceptual, decorum defying work behind the mask of conventional and well written realist fiction. His work often appears at first to be one thing (an off color story about fucking) and then he turns it into something else (a pointed story about political lineage). Reading his work I frequently realize that he has got me; he has played with my politesse and made a joke of it.

Wars. Threesomes. Drafts. & Mothers, Yépez’s first single author book in English (he has oodles in Spanish), is similarly provocative. In terms of genre, it is probably a short novel. It mainly has three characters: two twin brothers and a woman. And the story starts in Tijuana with an attempt by one of the twins and the woman to pickup a failed romance. But really, not much beyond conversation and self-reflection happens in the book and there is much talk about drugs (is the brother using or not?), sex and sexuality, jealousy, and parental abandonment. As the book proceeds, the frame keeps shifting and the narrative is interjected with things like writing exercises, something that might be authorial commentary (“This story I’m reading now was written for a reading.”), and Michael Palmer, Don De Lillo, and Reinaldo Arenas quotes. The novel comments frequently on how it is written in English.

But it isn’t just that Wars. Threesomes. Drafts. & Mothers is mainly a novel, it also seems to be a romance. But an exploded romance. It starts, as the romance usually does, with the couple meeting up again. And like many romances, which often feature lovers from opposite sides of border disputes, their union is used as a way to talk about relations between nations. At moments the couple represents the north and the south. At other moments it is the US and Iraq: “In every couple there’s a United States and there’s an Iraq. ‘United States’ is the so-called-victimizer. The master that ejects violence. The psy-ops, the war-words, the troops he sends (The Kids!). And then—on the other side—the so-called-victim. The so called poor-little-you. The one that doesn’t deserve the treatment you’re getting, your bad-bad luck, the you-know-who. ‘Iraq.’”

But because Yépez is primarily a provocateur, not a reconcileur, the romance plot keeps going astray and mutating into something that suggests there are no easy and conventional answers to the political questions of today. The woman, in addition to being a former girlfriend of one of the twins, is also part of a threesome in Toluca. The twins, at moments are twin brothers and at other moments the narrative voice suggests that they are an invention of the writer: “I felt like I was two different men, and I started to call that situation <

>.” At other moments it is suggested that the whole story, threesomes and all, has been fabricated by one of the twins so he might “have something else in life.” Or the twins really are twins and they, similar to father and son Bush, have sex in the womb and outside it also. In other words, Yépez refuses to restablish the couple, to end with the conventional marriages of the romance.

It might be stretching things a little to read Wars. Threesomes. Drafts. & Mothers as a romance. So perhaps another way to think of this book is as an equivalent to the “I am Bush” statement. I remember a friend angrily claiming that he was not Bush, that he had not started the war and neither had Yépez, after Yépez’s talk. But Yépez’s point was more subtle and multiple. It suggested that involvement in the oil wars extends beyond individuals and nations. It rejected lefty narratives of US exceptionalism (the sort of assumption that the US is so exceptional that it does horrible things all on its own; that other nations have no involvement) and first world passive guilt. It pointed to the ties between the US and Mexican government, the complicity of US and Mexican citizens. It rejected the idea that anyone could be innocent of anything. Wars. Threesomes. Drafts. & Mothers does similar work as it suggests that our personal romantic relationships carry wars in them. (This is a diversion but it is also striking how this book does not fit easily into US definitions of “border literature”; yes, Yépez, like many writers of the border, moves between Spanish and English but the book is fascinatingly devoid of “local” markers and descriptions, ethnic exceptionalism, nationalism, etc.)

Although part of me wants to keep returning to the romance genre because the book does end with a collapsing and exploding couple of sorts for Yépez ends with 9-11 and the twin towers: “The two planes not only announced the end of an era, but they also showed what was happening inside our lives. I read 9-11 as the crumbling of two people together, as the failure to stay next to each other, standing. And one tower was Emily, and I was the other tower, the first to fall. And then one tower was my brother and the other tower was me, and we both were destroyed by the world. And one tower was my father, and he became dust, and other tower, my mother, and she became a scream. And the two towers were love.” - jms http://swoonrocket.blogspot.hr/2007/07/forthcoming-poetry-project-newsletter.html