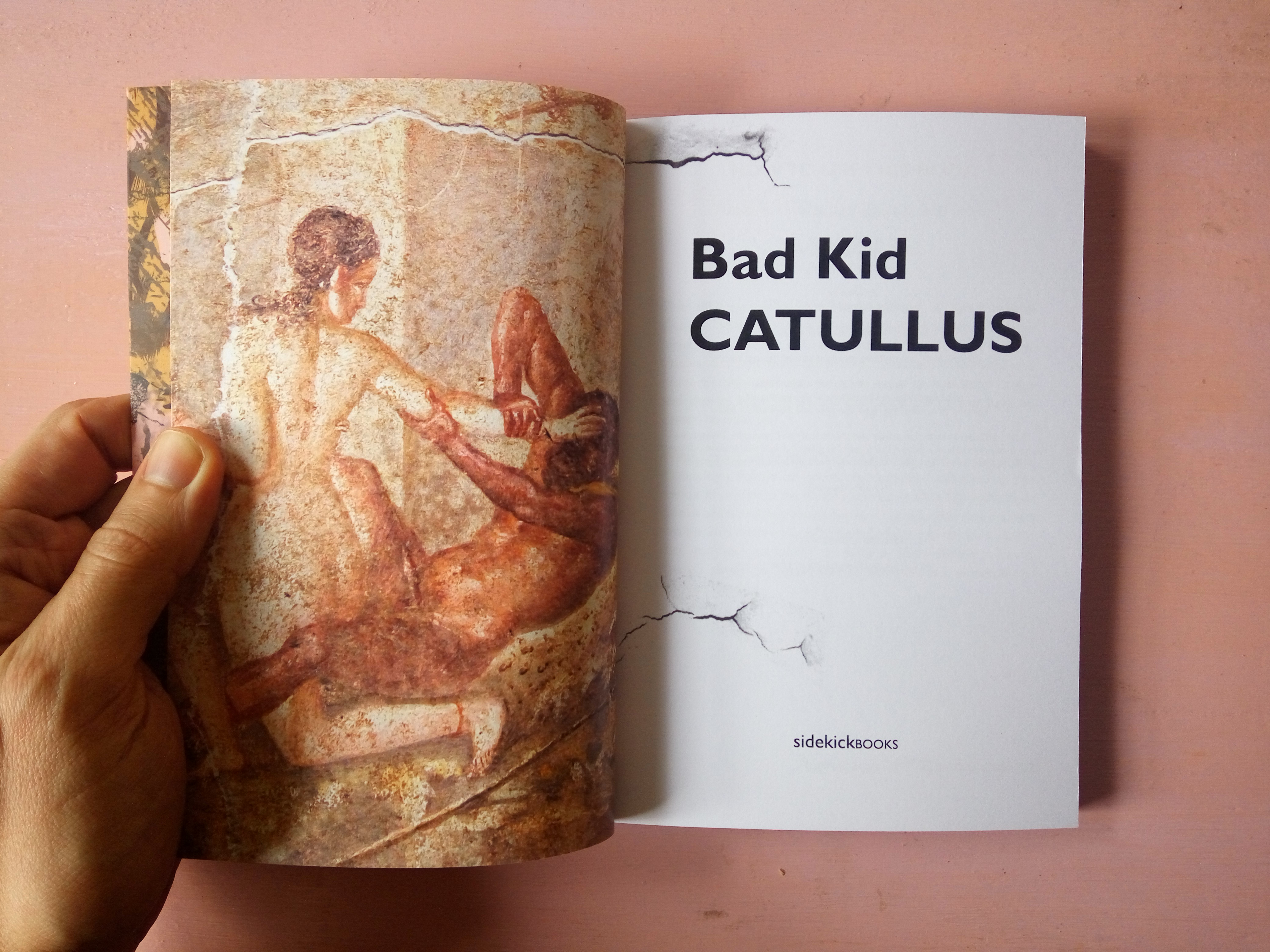

![Image result for Nathanaël, Feder, Night Boat,]() Nathanaël, Feder, Night Boat, 2016.

Nathanaël, Feder, Night Boat, 2016.

A singularly adventurous contribution to the worlds of mystery fiction, philosophy, and photography

With an English as ebullient as it is macabre, Nathanaël’s novel plunges its reader into a filmic world redolent of unsolved crime and suspicion. Part noir, part philosophical investigation, part literary subterfuge, Feder tenders image over evidence as it exfoliates the inside-out life of its protagonist Feder, at once aloof and queerly omniscient, with a propulsive intimacy that all but breeds a sense of the narrator’s complicity in the narrative’s central travesty. In this reality, municipal sewer systems are brimming with bodies drifted in with the tides, the last century’s architectures have gone unpeopled, and a minor mishap on a tram can cause the sudden death of a stranger across a continent. Feder offers no simple set of problems and solutions, but the texture of an electric curiosity at play in language.

Somewhere between philosophical treatise and pastiche of a high-modern novella, Nathanaël’s Feder: A Scenario marks the author’s tenth volume with Nightboat Books. Beautifully designed, Feder follows its eponymous main character through his mundane life of steady bureaucratic labor in a highly regulated dystopian society, “a world of silence” not altogether dissimilar from the contemporary United States. The narrative, stylistically broken and spliced, follows Feder to the moment that this mundanity is broken through linguistic and temporal revelation. “Tomorrow is not a word that had occurred to Feder before. The whole mechanism grinds to a halt.” Unfortunately for Feder, these revelations have lethal consequences.The book is invested in the traditions of authors like Albert Camus, Anne Carson, Julio Cortazar, and Maggie Nelson with its intellectual rigor and theoretical underpinnings (sharing, with Nelson for instance, a great respect for Wittgenstein). Decidedly cerebral, Feder doesn’t just involve the mind, it takes place there; the associative, disembodied voice of a narrator is quite nearly pure intellect. So much of what we are allowed to see of this world, just in snatches, is architectural, the manipulation of light and space acting as a kind of structural inspiration for the narrative. What’s more, the philosophical mode has poetic qualities and both of these are dressed up in the façade of prose. This was a mode of many the philosophers in Feder’s pages: the fictional scenario to illustrate a point. While the prose is occasionally opaque in intention, the book finds its denouement in a remarkably beautiful lyric section entitled “Topography of a Bird.”

“The bubonic hour is reserved for everyone,” the Delphic narrator says in this final section. Perhaps “Topography of a Bird” appeals to the reader as a kind of rich foil for the relatively stark syntax of the rest of Feder. The section itself is concerned with a certain kind of revolution after the death of Feder, even if only a personal revolution in the thought processes of the two characters, Anders and Sterne, who reside in these lush sentences

Carson has her deft humor and Nelson a lively messiness, even Camus and Cortazar have the weight of sheer weirdness to balance out some of the denser portions of their texts. Nathanaël uses the immaculate structural intricacies of pretense and simulation as a counterweight for Feder’s density. There are so many gestures toward recognizable narrative and familiar structures. The art in these gestures lies in that fact that they rarely resolve, instead often getting purposefully obscured in technical jargon or minutiae. These gestures are laid atop one another until, to borrow an image from the book, like so many images on a single piece of film they lose all sense of immediacy, “a thick amassment of detail, so intricate as to be indiscernible. . . . The surface fallen from itself, as it were; a strange luminescence.”

So often these narrative structures imitate riddles, or games. “For a moment Feder believes he is being watched. It is a game he likes to play with himself.” This comes, again, from the philosophers’ scenario method of explanation: If we have someone named Feder with y and z qualities and we understand that the world in which he lives has a and b conditions and he is put in whatever situation, what happens? In this way revelations can be thought of as parallel to punchlines. The thing about this book is it never reaches a punchline or revelation, instead exploring scenarios via non sequitur and collaged narrative structure.

“We have made ourselves manifest. Now, there is no one left to see.” When Feder manifests himself as a temporal being, one with a past, present, and future (or put in a more classical context a beginning, middle, and end, therefore manifesting as a dramatic being, as well), he comes to his end. In much this way, the book itself defies understanding, glancing off direct appeals to meaning. Its genre is amorphous, its style at turns deeply engaging then coldly exclusive. Feder is a puzzle, a dramatized mental game, some rules of which readers might feel like they are missing. But, this reader is certainly ready to hear the riddle again; maybe next time I’ll catch on. - Trevor Ketner https://www.lambdaliterary.org/reviews/01/21/feder-a-scenario-by-nathanael/

Writer and translator Nathanaël’s (The Middle Notebooks) latest is a slim, obscure “scenario” in which philosophical musings on architecture, the photographic image, and epistemology are layered atop a bare-bones narrative foundation. History, this elliptical book seems to imply, is too violent, chaotic, and vast to perceive in all its complexity; rather, the historical record is like a photograph left “to macerate too long in the developer... [a] thick amassment of detail, so intricate as to be indiscernible.” The enigmatic protagonist is Feder, “a man, who is no man, in a time, which is no time.” He is a creature of habit, marching up the same stairs to the same desk in a soulless architectural complex, where he works as a functionary assigned various vague tasks. Feder investigates an unidentified corpse languishing at the bottom of a stairwell, only to be eventually deemed guilty for some unspecified offense. The cipher-like Feder is at once vital to the smooth operation of the state mechanism and utterly replaceable, a body as expendable as the ones constantly washing ashore and onto the city streets. Thick, theory-heavy prose abounds—“The coincidence of reflectivity and transparency provokes an unresolvable somatic contradiction which is most apparent at a building’s flexion”—but Nathanaël’s idiosyncratic vision and patches of desert-dry absurdist humor add a pleasurable element to the reader’s book-length bafflement. - Publishers Weekly

There are some works in literature that attempt to express the ineffable. Kafka was one of the practitioners of this dark art. Joyce, Beckett. The Modernist canon contains some of these heroic attempts to make intelligible a sense of the absurd that has crept into the consciousness and conception of human history, of human existence itself. Some writers, like the existentialists of the mid-20th century, used almost conventional narrative devices to convey to the reader what is being attempted. I think of Camus’ “The Stranger” or “The Fall”, or Sartre’s “Nausea”.

Within this tradition of Modernity is an oft-neglected strain of narrative and writing that arises with the early 20th century avant-garde. Cubism, Futurism, Surrealism; spanning countries as diverse as Russia, Italy, and France, these three movements of the avant-garde brought (amongst other artistic accomplishments) written works like those of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Emilio Settimelli, Daniel Burliuk, Daniil Kharms, and Velimir Khlebnikov.

The tradition of the experimental novel has far from been abandoned. Some writers have even gone on to have some success (or at least a succès d’éstime) with mild experimentation (such as Donald Barthelme, William Gass, or Flann O’Brien among many others).

But what is experimental literature? An easy definition is that it is written work that emphasizes innovation and technique. If this is the case, most experimental literature fails to interest because it is not interested in deeper subjects or themes.

In “Feder”, the latest book by Nathanaël, experimental literature achieves a certain kind of apotheosis as technique is merged with a philosophical sensibility that creates a poetic vision of darkness that is both mesmerizing and aesthetically beautiful.

Nathanaël, author of over twenty books including translations of experimental writers, has been tracing an interesting path in literature that deserves to be followed. Her work is usually presented as essays, but they are more than that. I have seen where they are described as “intergenre”. And this, I believe is accurate. The limit of any definition is in our attempts to describe her work using conventional descriptors, not in the work itself.

“Feder” is a self-described “scenario”, but perhaps the word is used in English (where it exists with one meaning) but meant in French (where it exists but has a different meaning). Since Nathanaël is both a French and English writer, she uses the English language much like Nabakov, using certain words as in the above example, words that may have multiple meanings in either language, or words that may be neologisms but when read in context, they are immediately understood. This suppleness, this plasticity demonstrates an ability to view and use the English language in ways perhaps a unilingual English writer is not capable of.

This is not a novel, but it isn’t poetry, either. Indeed, to me it reads more like a “screenplay” of an imaginary movie that can never be made due to the impossibility of realizing mise-en-scenes that could not be reproduced on celluloid, oneiric imagery of the type found in one of the hermetically-packed paragraphs such as this: “The water was brought to a very high temperature according to custom and the people moved around on their knees. In moments when the structure was overturned, the people appeared to be suspended from a sky of concrete.”

![]()

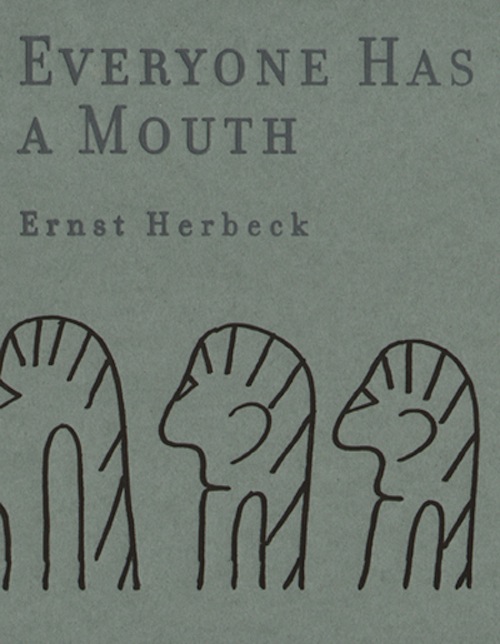

Nathanaël, The Horses That Come Out of Our Heads

Continuous movement coupled with the inability or unwillingness to settle down in one place or another is not exactly something that most people are accustomed to grasp without harsh judgment (acknowledged or not), especially when the subject of movement is perceived as a “woman” expected to embody domesticity, or more accurately, docility. On such adverse terms, experiencing an acute sense of displacement and alienation comes as no surprise, and eventually, the force of gravity inflicted by the reality might force one’s thoughts to materialize into words on paper, even if the paper might very well be shredded to pieces later.

Registering rituals of migration similar to the ones performed by non-humans while also trying to wipe out distances of various nature, Nathanaël’s The Horses That Come Out of Our Heads is forwarded as a chapbook that folds and unfolds according to its own invisible maps, in the same way non-humans (particularly birds) use landmarks to chart their territories and movement patterns, landmarks that are most likely to stay imperceptible to the human eyesight and logic. It is a sequence of arrivals and departures, all marked by the dreary feeling that there is actually no escape from constant surveillance, internal or external — in fact, all animals see to be living under a totalitarian regime of some sort and humans are no exception.

There are shelters along the way, spaces inhabited by silences and ambiguity that are safe as long as they preserve their anonymity. They are spaces that also function as places of passing and mourning. But the defensive, even murderous architecture, with structures and patterns that refuse comfort to the homeless while also erasing the brutality of colonial past and enslaved labor, is still here, a reminder that “natural” flows have been interfered with and manipulated by humans in a narcissistic endeavor to reflect their own image. One might choose to look at such buildings in awe, but this would also mean that the gaze has been tamed as well — to naturalize murder by erasing any evidence of it.

The French, as much as the Americans, are more or less dissimulated arms dealers; even though it is said that hunting grounds are better managed in the United States — but this relativism is already suspect to me — I question this word management which is nothing more than a permission to kill, which cloaks itself, then, in the force of the law in order to exonerate itself both of its malicious intent, and its wile.

The admiration that a cathedral or some ancient construction can incite should at least be mitigated by just as vast a sentiment of horror as to what its construction entailed in slavery, and brought about as mortality (murder).

More often than not, voyages stand for mere escapism — immersing oneself in trendy scenery but without really listening or paying attention to the newly emerging contexts. These are also the kind of voyages that one takes without leaving preconceived ideas behind and which do little more than reaffirming the human expansion at the expense of everything else while compassion gets directed only at oneself, leaving no room for empathy towards other persons and getting replaced by narcissism in no time.

But with its sketches of blurred geographies and doses of memories and writing that collide against instances of biting loneliness and self doubt, The Horses That Come Out of Our Heads does more than simply defying conventional genres, particularly the linear, chronological storytelling avowed by the memoir genre. It also refuses any kind of closure or nostalgia despite being assembled from memories that might stand for a subtle attempt at surviving banalities and disturbing realities without using journeys as an easy way out. One’s body might find rest in self-imposed solitude and the spaces between things without limiting them, either by defining them in human terms or perceiving them exclusively through normative lens only to modify them later. Writing attempts that are not committed to recalling anything can even obscure this body, but not its desires.

The most atrocious orgasm is the one that arises in sleep. The wound of what sleeps, and sleeping, breaks against the body, the very rock of the capsized, all drowned, off the shore of that unhabituated desire.

I sleep and I come. You are waiting for me there as ever you have awaited me, younger, alive. There are no ghosts, only the extension of a cruelty which belongs to oblivion. You come out of oblivion and you say: You love me. More than anything and anyone.

Nathanaël,The Middle Notebookes, Nightboat Books, 2015.

Winner of the Publishing Triangle Award for Trans and Gender Variant Literature

Nathanaël’s philosophical notebooks propose a poetics of intimate engagement with mortality. The Middle Notebookes began in French, as three carnets, written in keeping with three stages of an illness: an onset and remission, a recurrence and further recurrence, a death and the after of that death. But the narrative only became evident subsequently; the malady identified by these texts was foremost a literary one, fastened to a body whose concealment had become, not only untenable, but perhaps, in a sense, murderous. It is possible, then, that more than anything, these Notebookes attest both to the commitment, and the eventual, though unlikely, prevention of, a murder.

All of Nathanaël’s prose seeks the terminal poem, the poem that passes into action, that passes through the window, invents the outwards of being, which is not being but becoming, innocently. There is no more prosaic poem than what today Nathanaël’s writing attempts. For this poet narrative speaks of nothing, it doesn’t evoke, nor does it convoke: this writing is in movement toward the new man, the origin and the end of all philosophy as of all literature. In hatred of the novel and in hatred of the cinema, Nathanaël invents a new manner of registering and of representing the humanized living. Let us name this an erotic pictogrammatology. —Alain Jugnon

Nathanaël,Sisyphus, Outdone.Nightboat,2012.

Here, Nathanaël engages the catastrophal—photographic, translative, architectural—calling to the scene a discrepant combinatory of voices including Ingeborg Bachmann, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Dmitri Shostakovich, to insist on the relational and seismic state of language and the image.

“Troubling borders separating disciplines, dividing countries, and distinguishing words, Nathanaël’s texts borrow meticulously and programmatically from other authors, literalizing the Barthesian ‘tissue of quotations’ as they also draw incestuously from, and thus plicate, her own oeuvre. Each writing is thus in itself, and in relation to Nathanaël’s larger corpus, beset by the calculated vertigo of écriture, as Nathanaël enacts obsessive returns to a cluster of characteristic concerns, each time with a change of lens that profoundly informs her renewed scrutiny and its consequences.” —

Judith GoldmanSisyphus, Outdone. Theatres of the Catastrophal, by Nathanaël, was launched into the world at the Corpse Space on Milwaukee Avenue last Wednesday evening, in the presence of the author and Daniel Borzutsky (my discussants in open conversation), and a sizeable yet intimate crowd.

This is one of a score of books recently issued by Nathanaël, who writes between genres: that word

genre referring to both genre and gender, in the French sense—in what is much more than a pun transgressing tongues, but instead a primary aperture onto the unflaggingly, unapologetically seismic, fracturing and yet twinning, hermaphroditic terrain of this author’s mind. I was asked to open the space to a voicing of this latest text, which is in conversation with all of the prior, and whose very body models the reconception of the self as, to cite Nathanaël, “in seism.”

I’ll transcribe here my opening remarks as moderator about the text as counterboulevard:

The work is clearly related to Nathanaël’s earlier texts in being composed as from within a thicket of discussants, both living and on paper, and including herself. However, formally speaking,

Sisyphus, Outdone pulls itself apart to a greater extent. It is as though the threads in what Judith Goldman justly calls Nathanaël’s “tissue of citations” had been yanked convulsively to make the threshold/voids between voices more palpable—as in translation. The frontispiece in fact features the formula for the “equation of dynamic crack growth,” courtesy of Michael O’Leary.

I think of course of Benjamin’s

Arcades Project, since Benjamin was the one who said of translation that “if the sentence is the wall before the language of the original, literalness is the arcade”: literalness being a structure of innumerable, unapologetic thresholds.

In the open thresholds signaled by white space on the page we are subjected to the difficulty, and silent undertaking, of advancing from one voice or citation to the next in “disappointed bridges” (cited from Joyce on page 53), “Bawling by architecture’s apertures” (68).

And in fact, the status of the “advance” is thrown into question by this work, which is constantly doubling doors, seeing the threshold of text and abode as both exit and entryway, a text that can reverse, repeat, revise, the “instant cast backwards.” And this itself has to do with the “repetition at the heart of catastrophe” that Cathy Caruth theorizes and Nathanaël reperforms.

-

oikost.com/Sisyphus, Outdone.Theatres of the Catastrophal

In lieu of an abstract, here is a brief excerpt of the content: [ extract ]

§ "Ways of dying also include crimes."

§ I feel myself of another time, as though there were other time.

§ Side by side or superimposed, Paul Virilio's Tilting bunker and Michal Rovner's Outside #2 exacerbate - they reiterate - the time of decay : Rovner's over-exposures bring to the surface of the Bedouin house its temporal degradation, granting it oblique equivalency with the bunker sinking into the sand. Rovner slows time, measuring its imprint, extruding from the house in the desert the implanted time of accelerated degradation. What Virilio's bunker exposes (documents) Rovner's anticipates by ennervation. There is the subjective disclosure of the subject's disintegration in time, in a frame. What I see, in each instance, is not a house nor a bunker, but the work of time, the anticipation and accomplishment of death's (de)composition.

§ Un événement de lumière.

§ An event of light which is or might be a storm. Light storming the house in the desert. Light, which in this instance, is, has the potential to be, catastrophal. Bringing about. Standing the house more still.

§ The photograph lacks definition. A world (worlds) undefined.

§ The photograph does not lack definition. It draws out that which by definition is undefined. Undiscerned by instrument. Absent of designation.

§ Do I kiss it back.

§ Death's (de)composition is (also) a theatre of war.

§ What are we waiting for.

§ In Guy Hocquenghem's aspiration to objectless desire and Hervé Guibert's consideration of subjectless photography there is the intimation of the removal of a self in order to unburden a context of its context. A voice without language or touch without touch.

§ "La sexualité indépendante de tout objet ... sujet et rejet même."

§ In the last of language, language is subjectless. It ruins itself against an embarrassing hope for more. Its perversion is less than this. Less than its desire for itself.

§ Its rejection.

§ A ruined language is a language with neither subject nor object. It says nothing (or too much) of where it has been. Intimacy is, in this instance, intimation: "La ruine nous conduit à une expérience qui est celle du sujet dessaisi, et paradoxalement il n'y a pas d'objet à cette expérience."

§ Who was there in the first place.

§ The door is always open. This might be History's proviso. An inhospitable hospitality. Suspect and ill at ease.

§ The I might be a catastrophist. Taking turns. Turning out.

§ Seismically speaking, a split self is rendered unavowably speechless. Self without self. Irreferent.

§ Is it for lack of place.

§ Or: a siteless retort, pronounced out of place. The site ridded of seeing may be a way away from pronouncement. Built or borne.

§ This is Heidegger's declaration: "The proper sense of bauen, namely dwelling, falls into oblivion." This is the case, also, of the proper senses. Undwelled, obliviated.

§ The impropriety with which, for example, we are secluded.

§ For example: we bereave the sense of our freedoms.

§ A house which is built into its destruction.

§ RY King's photographic dissolve marks the paper immutable. (

Figure 1) Immutable in that it is always imbricated in a mechanism of deterioration. In this improper sense, the image is not separable from its degradation. Its substances are both paper and light. Thus they are neither, as they run into each other.

§ The bird, in this instance, which is scarcely discernible, is in a field of apparent surfaces. It comprises the surface by which it becomes visible, an irregularity on a structure of hay bales in a field of depleted colour. The photograph misdirects its intention. It intends for me to fall in.

§ In to America.

§ The identification of a site is improper in...

Theatres of the Catastrophal: A Conversation with Nathanaël

By Geneviève Robichaud

On the occasion of the release of her most recent book,

Sisyphus, Outdone. Theatres of the Catastrophal (Nightboat Books, 2012), Nathanaël and I shared a conversation.

![Lemon Hound]() Geneviève Robichaud:It is the impact of the fragment, the assemblage, the collaborative element of your new book, Sisyphus, Outdone. Theatres of the Catastrophal, that interests me at this juncture and that compels me to gesture to certain parts of my traversée (not fully articulated as a réplique, per se, but as an experience nonetheless). I will begin with your own beginning, the one after the epigraphs, before the first series of tableaux begin. Je suis au seuil de la porte. It is the place where, in Sisyphus, “Someone carries a door through a door. | This is demonstrable.” Is there such a place as an in between space?Nathanaël:

Geneviève Robichaud:It is the impact of the fragment, the assemblage, the collaborative element of your new book, Sisyphus, Outdone. Theatres of the Catastrophal, that interests me at this juncture and that compels me to gesture to certain parts of my traversée (not fully articulated as a réplique, per se, but as an experience nonetheless). I will begin with your own beginning, the one after the epigraphs, before the first series of tableaux begin. Je suis au seuil de la porte. It is the place where, in Sisyphus, “Someone carries a door through a door. | This is demonstrable.” Is there such a place as an in between space?Nathanaël: It is unclear to me that one can speak of beginnings with

Sisyphus. It seems to me that with this work’s concern with belatedness, there is a refutation (possibly) of anything resembling an advent. To be perhaps too literal with it, the epigraphs are wrested from the midsts of works, the equation included with the epigraphs is extracted from a much more complex calculus, itself tied to an undisclosed conversation, and even the frontispiece, with its mathematical deliberations, is only part of a much larger problem.

Sispyhus itself, by which I mean the book, is residual at its very beginnings. One could, I suppose, make this claim of any text, since it is organised with elements of language that are themselves, of necessity, and by design, belated: they come after. Here, however, there is no assurance given that any beginning is without suspicion as to its instigation. Does the text begin where you have indicated (with, what might be treated as a further epigraph, or else a mathematical problem), or with the lone word “Still” with its semantic instabilities. If I am placing so much emphasis on the question of beginning, it is because of its eventual relationship to the between you have chosen to question. In

Sisyphus, I think the question is quickly dispensed with; this work is concerned with reiterative endings, moments just past the last, as it were, too late. As for me, if I granted as much attention as I did to a so-called between space, in prior works, it was, I think, in error; a temporal error that allowed for bracketings. Here, everything is at once gaping and violently contained.

GR: The idea of “the gaping and violently contained” is provocative, as is your method of culling citations from a large repertoire of works and authors, meticulously re-staging them to create a conversation between passages. I use the word “passage” here deliberately – not only to gesture to the textual fragments that are assembled in Sisyphus but also in regards to my own experience reading the work as a kind of traversée. What is the connection, if any, between the idea of a “passage” (especially if we consider the work of the passage or fragment as an invitation to move from one site to another) and the catastrophal, or is it the arrangement of the fragments, like a musical score, that results in the feeling that one is passing through something that re-emerges as the same, yet-not-quite-the-same? Another manner of posing the question would be to ask: to what extent has the idea of a false in-between, “a temporal error that allowed for bracketings” in your older works, made possible a kind of reification of time and perhaps even of space in Sisyphus?N: I might hazard, in return, that the traversals in question with their temporal inclination toward desuetude – the

passager, who is both, in French, passenger, and passing (transitory), substantive and epithet, which is to say, outdone, or overstepped, convokes the very threshold which is surmised at the outset of

Sisyphus, with the figure of the double door; though this is imprecise, it is two doors, most likely, one inside another, evidently a material impossibility, because this would imply the simultaneous occupation of a single point in space of more than one door. And here, I have elided the figure of the

someone carrying the door. What you identify as “the same, yet-not-quite-the-same” may already be indicative of the movement you ask after. I could say, for example, that for a time, I imagined translation as a movement between texts; in this case, the traversals are many; only the boundary across which the text must be carried, if we are to follow the by now much-abused etymology of the term

translate, reveals itself to be disintegrative, friable. Which amounts to the destruction of all identifiable coordinates – temporal or otherwise. In translation, I have come to understand that what is most ignored, in conversations about translation, is the moment at which the texts come to pieces; the boundary, amplified, is extenuated, it ceases to exist. The catastrophal, in this sense, disallows the convenience, the privilege, of an

interimary moment, because the reprisals are all driven into one another, with equal vigor and violence. I have no interest in making a theory out of this, but of thinking it through its own thinking – the most telling indicator for me, is in the misapprehension of language, and in its misconstrual of the mind, the body, whichever and however they contraverse one another. The various instances of this which arrive at

Sisyphus are already broken in the ways they reveal themselves to be. In a sense, this evidences the destruction of pasts, which are active in the time of the work as it is alluded to. An example of this might be Shostakovich’s decision to dedicate a quartet to himself (not incidentally the eighth). The composer anticipates the pall which has already fallen upon his work. To imagine himself dead, thus, and without a reciprocal text, compels him to determine it, to determine, in effect, his own post-mortem,

a posteriori, from out of his vital course. What happens, in language, and with this decision, is the confounding of times, and the belying, precisely, of

Sisyphus’s traversals. But it would be an error to place excessive emphasis on the citations collected into

Sisyphus. They arrive, fragmentary, and punctual, in the midst of a text that is otherwise concerned with its own indeterminate elaboration: which is to say it is a written thing.

GR: Can you elaborate on what you mean by “the moment [in translation] at which the texts come to pieces” (I love that idea) and what Sisyphus or the orchestration of the “theatres of the catastrophal” has illuminated for you?N: Translation’s disintegrative states have become something of a preoccupation; what I mean – and I’m still thinking this through – is that the instabilities instigated by translational acts are written into the text. Photographic processes have proven very instructive in relation to this. For example, Antonioni writes of the endless inscription onto photographic film of visual, material information that escapes the eye’s scrutiny. Prolonged development processes will reveal the ostensibly endless

latent images contained in a single frame of film. In theory, one could expose an image ad infinitum, culling from the celluloid more and more infinite detail. But we know from a photographer such a Josef Koudelka, who practices a very sensitive relationship to time, that excessive development will produce a pitch black photograph – one could imagine this as the absolute, the most complete photograph, in which the intricate detail produces a solid, impenetrable mesh of opacity. In which everything is inscribed and nothing is legible. A corollary exists in translation, and it is the moment at which the texts – foregoing the bilateral language of source and target texts (with its tidy between, and problematic direction) – the texts, with their languages, enter into disintegrative states. It has something to do with proximities and loss of intelligibility. It has something also to do with vigilation. The moment at which one is most focused might be the moment one must close one’s eyes out of sheer intensity. Something is, of necessity, eradicated, in one’s apprehension of — disaster, say. Absolute vigil does not, can not, exist. The senses cannot abide such demand.

A friend recently directed me to a photograph of the Chernobyl disaster – this photograph of ejected graphite from the Chernobyl core – literalises the exact problem I am referring to. The radioactivity is visible as a disturbance in the photographic field. And the photographer, uncredited, though likely a Soviet authority, died as the photograph was taken; the cause of his (?) death is both the photograph and the radiation. The two become indistinct and determining for one another. In this, it might be useful to return to several of the acceptions of

catastrophe, which are crucial to

Sisyphus, namely, a “final event,” “a sudden and violent change in the physical order of things” (in

Sisyphus, it is the seism, or earthquake, which functions as principle exemplar), and “the change […] which produces the conclusion of a dramatic piece,” all of which with their connotations of calamity. As I was writing

Sisyphus, I had in mind Genet’s text “L’étrange mot d’…” in which the morbid necessity for a particular kind of architecture of the theatre is argued. Fixity, the very phantasm of photography, becomes an ethical injunction – against the unsituatable fantasy of post-modern subjectivity. To respond to both fixity and disintegration as equally incumbent forces, rewrites ethics against a different acception of time. In my thinking, it has something to do with a way of thinking anteriority. Catastrophe theory is interested in precisely this sort of discontinuity; its apprehensions of imminent material change, for example, are predicated on an already foregone anterior state of flux.

GR:I am thinking about something you said earlier about not wanting to create a theory but instead thinking through the writing. Looking at your list of publications, I cannot help but notice how prolific you are, but also the degree to which a set of recurring preoccupations is worked out in each text. While I do not get the sense that these concerns are reiterated (in fact, I think your work is characteristic of movement and redefinition), I wonder to what extent each work opens up the possibility of another (or is it perhaps too simplistic to say that each work creates channels into the next)? Where has the process of thinking through the writing brought you this time? What’s next?N: It’s very possible (in fact arguable) that these channels exist, though they tend to reveal themselves (to me) after the fact. I can think of several prior, perhaps more determined examples of this, though they’re likely too tedious to narrate. Certainly the channels are not necessarily linear, in that there has been increasing enmeshment from one project to another, and the relays between works is rarely unilateral; one of the more complex examples of this might be the concurrent writing of

Carnet de désaccords, against an unfinished manuscript in French, and at least two other pieces of writing, one of which was the talk,

ALEA, on Algerian rooftops, as well as extracts from my end of various correspondences; the textual contaminations were multifarious and at this point, likely untraceable to an origin. In the case of

Sisyphus, Outdone., the conduit is made explicit in the epilogue to

We Press Ourselves Plainly, the last line of which is: “Sisyphus, outdone.” And for some time, while I imagined

Sisyphus, Outdone. as a translation of the

Press text, that consideration disappeared into other more immediate concerns tied to the actual writing of the piece. It’s probably safe to say that to recover that conduit would require a fair bit of excavation, and by that time it will have assumed another shape, bitten as it will have been by forms of decay. In the sense that the

Press text is concerned with a voice in a room,

Sisyphus, Outdone. is equally concerned with the parameters of a (the) room; or perhaps with the impossible autopsying of the destruction(s) evident in the

Press text (impossible for the exact reasons rendered in

Morendo, in which a body, on the verge of autopsy, and presumed to be dead, then discovered not to be, though already in a state of decomposition, is then subjected to the injunction to carry through with the morbid operation – in keeping with the portentous photographs on the wall). I would caution against too great a literalisation of this intention, though, since it is by now subsumed into something which, I hope, exceeds this aspiration (by now somewhat banal, and certainly of little interest if carried out with exactitude). If I make rules for myself, or if my work presents me with rules, as is often the case, I have no loyalty to them, nor to following them

à la lettre. There is thus a necessity of disloyalty to myself in all of this – this being that which escapes me in text. I wish to underscore this because of the dismaying conceptual fervor which seems to have taken hold of the century – not out of disdain for conceptualism per se, but for its limitations and the self-congratulatory effort that accompanies what amounts at times (and at its worse) to the simple carrying out of orders (one’s own or otherwise) with martial rigidity. There’s an ethical complaint in what I’m saying, but I won’t go into it here, though it may have something to do with the problem of vigilation which I discussed earlier.

”By now it is considered a truism that translation is the closest form of reading. I’d like to dispute this claim; not merely as a provocation, but precisely for reasons pertaining to the problem of vigilation, in which exacerbated attention provokes a kind of (I would say, necessary, however devastating) capsize, and what reveals itself at that moment of misalignment is of greater interest to me than the obvious concordances.”As for what’s next, if you are asking after chronology, last year and the year before I reinscribed the triptych of French language

Carnets into English, the most recent of which is

Carnet de somme. It became imperative out of a concern for concordance (of place, time, nomination, language…); these will comprise a single volume in English, under the title

The Middle Notebooke

s. If you are asking after questions I haven’t quite been able to formulate for myself, they are induced by some of what I was alluding to above, that is, elements of film, the photographic inflection of translation, and an irritable impasse vis-à-vis anteriority.

GR: This morning, while on the bus and reading from Sisyphus, Outdone, at random, a passage stuck out to me, which I read over and over: “what gives way is given away…this is what I understand of translatability…The point at which there is nothing left, nothing to motion over, nothing to speak for” (28). To me, this passage not only illuminates something about translation, it also points to something inherent in the reading act. How or where do the task of the translator and the reader align?N: I wonder whether they do. I’ve given some thought to this of late, and am still sorting through it. By now it is considered a truism that translation is the closest form of reading. I’d like to dispute this claim; not merely as a provocation, but precisely for reasons pertaining to the problem of vigilation, in which exacerbated attention provokes a kind of (I would say, necessary, however devastating) capsize, and what reveals itself at that moment of

misalignment is of greater interest to me than the obvious concordances. I’ve written about this elsewhere – in relation to intimacy and more recently to extinction – the ‘this’ being the lack of reciprocity that occurs in the midst of what might be idealized as absolute reciprocity (with the ‘absolute’ ever called into question). The first failed reciprocal relationship is that of the translated version of a text and the text being translated. Each bears the mark of that catastrophe. To take an example from Sisyphus, with its preoccupation with doors, Paul Virilio’s “trap doors open in a cement floor” translates the French “des trappes s’ouvrent dans le sol de ciment”. In French the doors disappear. But this is incorrect. It is in English that the door is made explicit; it appears, arguably, from nothing in the French sentence. The English makes manifest what is subsumed into the French

trappes at the moment of repetition (bearing in mind the French acception of répétition which means to rehearse). The

practised implications, then, for

Sisyphus are many, not the least of which the derailment of the text – without the doors, the sense is thwarted, the thinking cannot take place as before. One can also look away from the so-called original to concurrent versions of a work, for evidence of further forms of disjunction. The implications, for example, in Buber’s

Ich und Du (the very title of which incriminates the determined disjunction between the familiar

Du in German to the officialised formal

Thou in English), for an English reader of Kaufmann’s translation is radically altered in Bianqui’s French translation of a single line from the same text: Kaufmann’s ‘it does not help you to survive’ contradicts the intent of Bianqui’s ‘il ne fait rien pour te conserver en vie’. In my desire to come closer to German, I rerouted my thinking through French translations of the German; the multiplication of versions, rather than elucidating my reading of the text, further complicated it, interrupting the imagined proximities I might have written into my lecture. These are hazards, accidents of translation that inhibit reading. But what a formidable inhibition.

GR: “Formidable inhibition,” the title of a future project perhaps? Speaking of projects, you recently received a PEN Translation Fund fellowship for your translation of Hervé Guibert’s journals, Le mausolée des amants, which is due in 2014 as The Mausoleum of Lovers(Nightboat Books). So far, we’ve talked about translation in terms of transience (like photography’s misleading truth claim, especially as it pertains to fixity), disintegration and even the act of reading. But what about the incommunicable? (I am moved every time I reread the passage in Sisyphus where you cite Guibert: “j’ai besoin de catastrophes, de coups de théâtre”). Has translating Guibert’s Le mausolée des amants revealed or given you access to otherwise incommunicable realms of experience? Much has been written on the subject of haunted media, but what about the idea of a haunted sentence? What have you learned about Hervé Guibert that you didn’t know before you embarked on this project? What have your experiences as his translator revealed to you?N: The haunted sentence seems particularly fitting in light of an earlier work of Guibert’s,

L’image fantôme, in which the text bears the trace of absent photographs which form the armature of the work (a failed photograph of his mother, without which, according to the author, the book would not have existed). Guibert calls this

le désespoir de l’image. Transposed, one might speak, in effect of

le désespoir de la phrase; this may be the very plight a translator is beset with. The scale of

Le mausolée des amants (560 pages in the Folio edition) demanded, that at a practical level, I alter the way I usually work with a text – scoring the pace of translation versus revision differently – employing alternation rather than relying on momentum (this is aided also by the fact that the work is divided into a series of separate entries). But perhaps more strikingly, the intimacies that, as a reader,

Le mausolée des amants afforded me, all but disappear in the course of translation. “For if the sentence is the wall”, writes Benjamin – and in this instance, Guibert’s language is not visceral to me, in the way, for example, Collobert’s is – I translated a first feverish draft of

Meurtre in less than a week, and this has everything to do with the proximities that exist for me in relation to Collobert’s language – translating her, she is, in a sense, writing me, and perhaps even, with all due modesty, there is something of my own language that I find in hers; her language is intimate, visceral, her topographies familiar, and in that instance the boundaries tended to want to disappear – that was one of the dangers posed by that particular task: a willingness to go. With Guibert, it is otherwise, the distances are steadfastly maintained; there is never a moment at which Guibert ceases to be manifest in his own work, which is reflective of the kind of control he waged over himself, his photographs and his texts, even his film, during his lifetime. Translating Catherine Mavrikakis opened the way, not only to Guibert, but to this kind of demand, which requires the concurrent porosity (vulnerability) necessary for being thus penetrated by a text, and the vigilance necessary to resist conflating oneself with it. The violences committed by a text, even in such convivial circumstances, can be terrible. It is humbling to be so altered.

GR: Nathanaël, it has been a true pleasure and a privilege exchanging words, thoughts, ideas with you. You have been so generous. There is one more thing…with two new books out, (Sisyphus, Outdone. Theatres of the Catastrophal. Nigthboat, 2012. and Carnet de somme. Le Quartanier, 2012) are there readings that we (or our lucky friends across the border) should look out for? In Montreal?N: I thank you for your very engaging – and demanding – questions, Geneviève.

As for events, in the immediate, I am scheduled to give a couple of readings and a talk at SUNY Buffalo’s Poetics program (February 7 and 8). And the following month, in New York (March 10), I’ll contribute to a panel hosted by Nightboat Books at Poets House with Rob Halpern, Martha Ronk and Susan Gevirtz. As for Montréal, the city left me with its key. I would welcome the occasion.

-

lemonhound.com/![We Press Ourselves Plainly by Nathanaël We Press Ourselves Plainly by Nathanaël]() Nathanaël,We Press Ourselves Plainly, Nightboat Books, 2010. Nathanaël's blog

Nathanaël,We Press Ourselves Plainly, Nightboat Books, 2010. Nathanaël's blog“

We Press Ourselves Plainly is a particularly affecting development in an already virtuosic, Ovidian body of work because it renews and makes newly visible crucial continuities: between Continental and North American Postmodernism, the Nouveau Roman and New Narrative, WWII and Operation Enduring Freedom. From out of agile and Celinian ellipses, Nathalie Stephens creates an asynchronous, transnational ‘discordance…in time,’ a hugely amplified recent past whose familiarity haunts us not as nostalgia but as trauma. Among ‘immaculate and catastrophic’ ruins and lacunae, having forgotten ‘the sentence for behaving,’ the narrator embarks upon an ‘adverse and objectionable’ litany of a history whose abjections yield a kind of nihilistic courage: ‘Hope is for martyrs.’ Given that now ‘even the fictions are fictions,’ Nathalie Stephens puts ‘holes…where there were none’ as a way of underscoring that there’s nothing inevitable about gender or genre or violence, just as ‘What is inevitable is not the war but the language that determines the war.’ As grim as Beckett, as moral as Genet, as seductive as Duras—yet this book moves me like no other.” —

Brian TeareNathalie Stephens' latest prose-poetry book,

We Press Ourselves Plainly (Nightboat, 2010), presents itself as a continuous disaster (the disaster of incommunicability, of divided labor, of global warfare, of meaninglessness,"The whole of it") whose continuity prevents the disaster from reaching its apotheosis: the abolition of the text via its totalization.

The disaster around which the text orchestrates goes unnamed, unspecified; it is Blanchot's disaster, an engagement with the experience of death whose impending doom is postponed by the space literature creates. Such a space is typographically represented by ellipses being the sole form of punctuation, which act as a metaphor for an undecidedness, an intervention in time that recalls poet Tyrone Williams' line in

The Hero Project of the Century,

meanwhile means dissent.

The language, divided into incomplete sentences or complete sentences with referentially open pronouns, cannot be utilized (cannot, that is, integrate into an entirety, with each part an instrument of the sum). If we take it that the sentence is to language as the single commodity is to capitalism (both being the smallest utilizable unit), then such syntactic ruptures are a way of evading the specter of referentiality, wherein language would be exchanged 1:1 for the world it represents, absent any critical capacity, whereas here, without such a quantitative abstraction, we gaze at the language's

quality, its material presence. A sample:

Parcelled out the small formations into smaller ones... Tiny little disasters... Handled carefully and placed gingerly onto small metal trays... Then labelled... We make these manifestations into ourselves... What happens when... Shorn and emaciated... I forget all of it... The disordered remembrances... There is knocking... It comes from inside... A strangulation... The tripes pulled up into the ribcage... A thick elastic band... Not breathing... Heat in the skin of the face... The faces... Hands flipped back... A plasticity... It was touching... A hardness... Twist of a straight bone... Close to snapping... It releases... Leveraged... What do you suppose.... Does she mark time anymore... There is no sense... In the end the...It doesn't

What we notice about the text's material presence is also its absence. Composed of subordinate clauses, it's frequently written in the subjunctive mood (a verb mood used

to express various states of irreality such as wish, emotion, possibility, judgment, opinion, necessity, or action that has not yet occurred). This is significant because it implies counterfactual times of action, such as reformulating the present in light of an imagined one, wherein "The projection declare[s] a form of disappearance..." (29) at odds with the society of the spectacle whereby the modern spectacle (as in the image of the real concealing the system of labor producing it) "expresses what society can do, but in this expression the permitted is absolutely opposed to the possible" (Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, 25). The subjunctive then is an expression of the contingent, referring to displaced times not crystallized in the "totalitarian management of the conditions of existence." Thus we're in an asynchronous tense the breaks from the objectified present in which our world is usually communicated to us. For example "What happens when" questions the future while "I forget all of it" disables any such active contemplation. So the language wars with itself. Just when we think a plot is developing outside the development of the text itself ("There is knocking") we find "It comes from inside," bringing us back to the zero point. Stephens' provocative endnote gives a glimpse of their poetics: "The text operates a form of confinement, manifest as a continuous block of text from end to end. If one of the active functions of this work is compression, it is the compression not just of a body in a carefully controlled space, but of all possible spaces pressed into that body, upon which the pressures of historical violence and its attendant catastrophes come to bear” (103).Thus the text writes thru the structure in which the voices are "always already embedded in the structure they would escape" (Moten, Resistance of the Object, pg 2), performing one's enslavement as liberation as submission, where to read is to redress. - Nicky Tiso“I should like,” the narrator declares in We Press Ourselves Plainly“for my own name made illegible…” Indeed, we never learn the identity of the devastating speaker whose body and mind is the landscape on which violence unfolds. It is not a pleasant voice nor is it necessarily appealing, yet it enthralls in its immediacy, a distinctive intonation which begs the reader to devour it in its singular attempt to articulate the tragedy of history.A 97-page book-length poem in the form of continuous blocks of text separated only by ellipses, Stephens endeavors neither to elucidate the source of violence nor to expose a chronological representation, therefore the fragments—some of which are complete sentences and others only partial slivers thereof—have the aesthetic of immutability and timelessness, a voice existing in the present moment yet also in the dredges of the past. “There is a room and there is a war” the speaker declares, yet the poem exists also outside of a room and concurrently in various locations: Berry Head (a coastal headland in the English Riviera), Paris, Hyde Park, Fallujah and Donostia (the Basque region of Spain). Perhaps there has been a war or there will be one. “The wars become one war” and “The wars are indistinguishable” Stephens writes, adding to the atemporality of the poem and the omnipresence of violence. The book opens with a quote by Franz Kafka: “Everyone carries a room about inside him.” which further puts forward that the location is the body itself which bears the carnage. The post-script furthers this idea of the body as an object of compression and cruelty, stating that one of “the active functions of this work is compression...of all the possible spaces pressed into that body, upon which the pressures of historical violence and its attendant catastrophes come to bear.”

This notion of compression, most prominently set forth in the book’s title, stems from the root of the word

press, which harks from the early thirteenth century Old French noun

presse which means “crowd, multitude.” The verb form also dates from the same century:

preser, “push against”. Though Stephen’s book is titled “

We Press Ourselves Plainly” (italics mine) the speaker in the book is a very convincing “I”; seldom does the “we” come into view, yet the overall sensation one derives from reading is a collective sense of calamity, as if the voice is representative for a multitude or nation, even if the experiences cited sound at once both ubiquitous and painfully intimate. “There was one country in particular…It became the particularity of every country...” Stephens writes. In other sections the voice seems to shuttle back and forth between a collective and the sentiments of a lover: “

The bodies that fall unheld into the next day…I would like to kiss you…The field of vision narrows with the century…We stand on one side or another of the century”.

Notably, when the “we” comes to the forefront it is often in this context of being on one side or another. “We stand on one side or other of the glass”, “We stand each on one side or other of the crossing line”, “We stand each on one side or other of the monument and it is the same monument.” This motive repeats itself with the “we” being on one side or the other of violence (p.47), a door (p. 55), skin (p. 75), name (p. 81). The last time this motif appears is on p. 87, but the object is modified in the latter half of the sentence: “We stand each on one side or other of a pleasure and it is the same

pressure” (italics mine). Here the word pressure takes on an agreeable, if not sexual connotation. This “being on one side or the other” subtly presents a type of political counterbalance which seems to be at threat throughout the entire text. The “We” seems to refer to a group of people on different but not necessarily opposing sides. Other times the “we” becomes the pronoun signaling a sexual relationship or perhaps the bond of two individuals forced into close confinement. “We slept in a single bed” (p. 11) or “

We are naked for the moment…I grant you this one torment” (p. 15) and “

We bear.. Bury…Heart spilling blood into the weakened parts…Vomit it into me..” (p. 39).

This dichotomy between singularity and plurality, while rampant in Stephens’ book, neither weakens or undermines the integrity of the speaker, though rectitude seems to be the least of his/her concerns. Rather this contrariety points to the existential dilemma of identity and the self. “A book is less the appearance of a self than the disappearance, a grievance against self,” Stephens wrote in her 2007 book “The Sorrow and the Fast of It.” The brokenness of the language in “We Press Ourselves Plainly” insinuates a further fragmentation of the self:

…All the buried things arise…The rivers with the bodies of everyone…Each save the first one…It crawls over me…There was one language and this was the son…I refuse the offerings…There are flowers in a vase…I throw them down…We wake and are watchful…The bodies accrue and we name them…Small rashes that spread over the skins…Our languages become enlarged with the grief…The body, in Stephen’s book, is continuously beaten, cut out or scourged by mysterious malaise like the “small rashes” in the above excerpt. Not only that, but the speaker is perpetually vomiting, as if in an attempt to purge itself of the trauma it has been subjected to. What happens to a speaker which is surrounded and inflicted with excruciating emotional and physical torture? The result for the reader is an erasure of the speaker and the self, so that the excess of remembrance that the speaker endures becomes a longing for blank space, an insistent forgetting or “a compression layered of other moments just like it.” (p. 23)

…Shorn and emaciated…I forget all of it…The disordered remembrances…There is knocking…It comes from inside…A strangulation…The tripes pulled up into the ribcage…A thick elastic band…Not breathing… Stephens has been compared, and understandable so, with Jean Genet and Hélène Cixous, yet for me Stephens manipulation of language and form is heir to a long tradition of French (though Stephens is French-Canadian) poetic innovation that goes back to Francois Villon and makes itself manifest in contemporary writers such as Edmond Jabès and Claude Royet-Journoud. The form of “We Press Ourselves Plainly”, simultaneously litany and lament, brings to mind Alice Notley’s “The Descent of Alette” in its aesthetic and also its use of punctuation (Notley used quotation marks to separate fragments in much the same way as Stephens utilizes the ellipses). For me, however, the most obvious predecessor of the form that Stephens has chosen is the short dramatic monologue “Not I” by Samuel Beckett which features the same block text separated by ellipsis. “Not I” explores the emotional upheaval experienced by a woman after an unspecified traumatic event. In the performance of “Not I” a black space is illuminated only by a bright light focused on a human mouth, which utters in a frenetic tempo a logorrhea of angst-ridden sentences and sentence fragments, quite in the vein of an audible inner scream. This inner scream is what Stephens has articulated so skillfully. -

J. Mae BarizoIn a review of

Touch to Affliction, Meg Hurtado describes Nathalie Stephens as “a tragic poet, in the word’s truest sense.” Stephens’ most recent book,

We Press Ourselves Plainly, asks what happens to a body, a mind, a landscape that has absorbed the history of tragedy and then manifests that history within itself. It’s not a comfortable question, nor an easy one, and the speaker offers few answers, but rather attempts to embody that tragedy in a speaker’s voice. From the book’s brief post-script:

If one of the active functions of this work is compression, it is the compression not just of a body in a carefully controlled space, but of all the possible spaces pressed into that body, upon which the pressures of historical violence and its attendant catastrophes come to bear.I’m honesty not sure I can say what it means to have “all possible spaces pressed into th[e] body” of the text (an ambitious project), but one feels in the voice of this text the “pressures of historical violence,” in the mind and body of the speaker, which are then pressed into the body of the text.

The book is composed as one 97-page continuous prose block, fragments of thoughts delineated by ellipses reminiscent most famously of Celine (also recently employed by Chelsey Minnis, though with sparser text and more abundant ellipses, and perhaps others I am forgetting or are unaware of). The effect of the ellipses is very much one of atemporality, by which I mean that the fragments feel snatched out of time and atmosphere; there is no feeling of progression in the prose, or consistent context, which NS’s* post-script indicates is part of the book’s theoretical design:

Spacially, the room is finite. But what enters, through the body of the speaking voice, orients thought away from its confines toward an exacerbated awareness of endlessly forming breaches.

One of the confines of thought is temporal relation to other thought, disrupted here by non-sequitur and repetition. NS’s employment of the word breach implies the intent to transgress—here, both time and space. Technically prose but not narrative, assuming many of the liberties we associate with poetry, this book slips between and out of generic expectations, another breach.

The world of

We Press Ourselves Plainly is one in which the seeming whole of humanity’s history of violence has come to bear in one traumatized voice; “we stand on one side of violence and it is the same violence,” NS writes, succinctly. Also: “We stand on one side of history and it is the same history.” The collective pronoun “we” feels expansive and inclusive—who is on the other side of violence and history? Someone with a different relationship to both, I’d imagine, but the author seems to implicate a whole swath of humanity in the “movement” of violence, which is the “movement” of history. Just as the “I” of this text is anachronistic and geographically un-pin-down-able, so is the “we,” so that the reader feels included in this history and its attendant traumas.

The feeling of apocalypse that pervades the book is not a promise of some future demise but the fact of our own insistent violence in

this time and

this place. It’s not coming, it’s been here all along. The evidence is all around us.

It is the same warning… The same war… I attend the funeral in Fallujah and in Hyde Park… Nothing happens and it is written down… There are manifestations… The regional differences are deprecated… I prepare for it clumsily… The groans rise off the moors and out of the hospital beds…The notion that all the wars are tantamount to one long war is iterated again as the speaker announces, “For the sake of simplicity the wars become one war” and “The wars are indistinguishable” (an astute and timely observation, as the rhetoric of any warring country tends to try to justify its war by distinguishing it from the other wars). As the text moves through time and space with its elliptical fragments, the speaker also invokes Chernobyl and Charonne,* as if to assure us that we cannot pin violence to one single geography, one time, one place. If the catastrophes of violence are “compressed” (to use NS’s own language) into one physical space (the book) and mental space (the speaker), the effect is dramatic and heartbreaking. What mind is strong enough to endure that much horror and not break? And then, as the semi-concrete artifact of the mind, what happens to language?

…

We stand each on one side of other of a violence and it is the same violence… In the mouth… The mouth foremost… I make a signature of it… A fount of praises and they are immaculate… Immaculate and catastrophic…So language itself becomes broken, as is both formally and substantively enacted by this work, but it also perpetuates violence, becomes an artifact and instrument of it. (

Et quel dommage.) It is perhaps for this reason that the speaker pleads, “… Stop speaking… Just for a time…”

Here, there is nowhere the trauma of violence doesn’t reach. The body, the singular, human proxy for the physicality of the world in general, continuously vomits, as if in a constant state of rejection (rejection of that which poisons us). It is overwhelmed by toxicity:

A small overburdened liver… A mangled spleen… We bear… Bury… Heart spilling blood into the weakened parts… Vomit it into me… []… How many times bereft… And swollen… Lumped grievously together… Striated and torn… It spreads indiscriminately to other parts…The notion of contagion is an important one, the idea that sickness spreads: from one part of the body to another, from one body to another body. This is clearly writ politically and geographically as well: it is said that violence begets violence, contagion on a global scale. NS represents the body as macrocosmic proof of this. (As I will suggest more fully below, it is possible the reverse is true as well; if shadow is contagious, why not light?)

A small promotional insert in the book declares that the project of this book yields “a kind of nihilistic courage.” The books insistent nihilism is perhaps most succinctly articulated in the final words of NS’s post-script: “Sisyphus, outdone.” A feeling of futility underlies much of the text, and for understandable reason. To flatten the time and space of history so that the totality of its atrocities feels immediate would indeed “overwhelm the spleen.” And yet, as the speaker comments, “if only it were otherwise.” It’s a lament that reads as if our suffering were absolute; but I can’t help but read the desire for a different world as the promise of it, or at least the promise of its possibility. Not that I think the speaker of NS’s book would be so optimistic; this is a philosophy exclusive of hope: “I make some progress… You blow on it and it goes out…” At the same time, I can’t help but think that the attempt to make art (like poetry, like this book), even out of the most egregious suffering, is always, in itself, a hopeful act, an act of endurance and an affirmation of applied intelligence, those things which have the capacity to change a damaged world.

It’s well understood that when we write, we choose our focus. And because our focus is finite, something is necessarily excluded (if I choose to write about Medieval London, I am probably not therefore writing about globalization in India). A few reviews ago, I wrote about the romantic pastoral as critically problematized simply by virtue of all that it excludes about the natural world (it prettifies that which is not always pretty); reading this book, I wonder if the reverse is also true, and what its implications are. What I mean is, if the pastoral is felt to be problematic because it excludes the ugly, is work which makes its focus catastrophe, disease, etc., problematic because it excludes the beautiful or wonderful or sublime? And if not, why not? Can we say that one exclusion is truly to be preferred over the other? Or that one is more responsible?

Here is a probably woefully poor analogy: let’s say there is a terrible car accident. Twisted metal, mangled bodies, blood, injury, death; the bodies are in distress, there is fear and unimaginable pain (you could insert a scene of bloody violence here if the car accident analogy isn’t working for you). Now let’s say that people gather around this car accident holding large mirrors in front of their bodies. For those inside the accident, their whole world becomes a scene of horror. Everywhere they look around, there is only suffering. I wonder if the world we find ourselves in isn’t a bit like that—there are scenes of unimaginable horror; but what we hold a mirror up to multiplies the original horror manifold.* As NS writes, “It is the same violence… in the mouth.” I am not saying we shouldn’t hold up these mirrors, but I am saying it’s interesting to consider the implications of them, and whether the imperative to witness might include bearing witness to those things that help us endure the historical and personal traumas we are compelled to endure.

———-

* The front matter of the book uses “NS” for Nathalie Stephens, which I have preserved here.

* Known for the Paris Massacre of 1961, in which at least 40 (and as many as 200) Algerians were slaughtered.

* This seems especially the case given how many different kinds of mirrors we have available to us via television, internet, poetry, art, photography, film, journalism, etc., etc. -

Christina Mengert

(Self-)Translation: An Expropriation of Intimacies, in Phati'tude, ed. Timothy LiuNathanaël,The Sorrow and the Fast of It, Nightboat Books, 2007.The Sorrow And The Fast Of It exists in a middle place: an overlay of indistinct geographies and trajectories. Strained between the bodies of Nathalie and Nathanael, between dissolution and abjection, between the borders that limit the body in its built environment--the city and its name(s), the countries, the border crossings--the narrative, splintered and fractured, dislocates its own compulsion.

"The Sorrow And The Fast Of It is a severe and tender book in its 'incalculable' correspondence between ocean and ground; the one who writes, and the one who receives."—Bhanu Kapil

It exists in a middle place: an overlay of indistinct geographies and trajectories. Stephens writes strained between the bodies of Nathalie and Nathanael, between dissolution and abjection, between the borders that limit the body in its built environment--the narrative, splintered and fractured, dislocates its own compulsion. "Stephens is obsessed by breaking free, only to find herself brakeless"—Andrew Zawacki.

“Only the writer who astonishes language, who dares to tamper with it, is worthy of the epithet,” writes Nathalie Stephens, and she lives up to the challenge she sets—hers is a use of language that alters the language as she uses it. And in her case, this means two languages, as she writes in both English and French, often using one to infiltrate the other, to crack the other open. Often we sense the two languages passing each other, and as they do, a charge arcs from one to the other, making each stand out in sharp relief.” —Cole Swensen

“A voice,” Nathalie Stephens avows, “is an occurrence of madness.” Indeed, the specter of la folie is rampant in her latest book, The Sorrow And The Fast Of It, and it happens under a damning, double sign: there is the going mad, and there is the consciousness of it. The awareness is an intensification of the malady. As Michel Foucault and several of his notable contemporaries elaborated, with their sights trained on Sade, Lautréamont, Nietzsche, et al., writing is subjection to madness, and madness means the shutting down of the subject. Across the five untitled sections of an even hundred pages, Stephens struggles to negotiate what is precisely the impasse or impossibility of negotiation. “I liken speaking to an epitaph,” her speaker admits, thereby succinctly enacting her own demise. As she recollects, “I fancied myself the vestiges,” having suffered the onset of madness at age twelve. “I was born in the midst of demolition,” then, both literally (a church was being torn down nearby) and figuratively, one self emerging, cauterized but charred, like a phoenix from the adolescent flames of the other. Paradoxically, a “suicide begat me.”

Taking a cue from Shoshana Felman, “If madness is indeed an excess of remembrance,” Stephens avers, citing Writing and Madness in ghostly grayscale, “I have come to this embouchure to argue against remembering.” For Stephens, while madness certainly involves extreme levels of distress, it is not because everything passes, although that is true. Stephens is not haunted by la recherche du temps perdu, and her mode is far from elegiac. What wracks her book is less separation or absence, be they physical or temporal, traditionally the harbingers of melancholy, and less the fading memory that, according to the Proustian paradigm, invites sadness. To the contrary, Stephens revises the ventured thought that, “The distance was too great…,” by reversing it: “…Wasn’t great enough.” Apartness is not a problem in this book—claustrophobia is. Without sufficient remove, minus any fixed exterior point, life becomes infernal: “I went to Hell,” she recalls, where Cerberus guards the entrance to Lethe, river of oblivion. Unremittingly in-fernal, living inside “A body overful of wanting to forget,” Stephens’s speaker is overwhelmed by the immanence of immediate experience. “There is a fever that overcomes,” she says calmly, seeking the consolation forgetting might bring. Her pain ushers not from desire for what’s been lost but from a hyperconsciousness of what she cannot lose. Fascinated and frustrated by the “thing pushed away that remains,” Stephens commits to the quasi-mystical eviscerations that Simone Weil calls decreation: “we are the thing that needs removing,” we “[n]ot so much want as want not.” Madness here is neither amnesia nor nostalgia, but the inverse incapacity to erase. Freighted by the sheer limitlessness of a conscious mind without remainder, Stephens needs the opposite of anamnesis or analysis; it is exorcism she solicits, the via negativa, “Surrender me,” vomiting and cutting out and bleeding.

Hence the proposal that it is “possible,” as Stephens puts it, “a book is less the appearance of a self than the disappearance, a grievance against a self.” The self already an unstable artifice chez Stephens, she does everything in her power to raze it further. “I would want to be manifold,” she avows in the conditional tense, perhaps acknowledging a utopian aspect to that hope. As her prose shuttles limpidly between “I” and “we,” the speaker, or speakers, cannot decide on her (or his, as we shall see shortly) or their identity or identities. An interdiction against simultaneity comes into play: “When we go to speak,” Stephens observes, “only one of us survives.” When I say “I,” that is, I am not “we,” and vice versa. This dichotomy reigns in the book, tyrannically. It becomes clear rather quickly that Stephens, however, is not interested whatsoever in discerning between singularity and plurality, let alone in choosing a side. Disobedient, she has decided not to decide, for she wants the self, and all its categorical exclusions, excluded categorically from her writing.

The dilemma between unity and multiplicity is not, however, the only existential knot that Stephens endeavors to untie: singularity is itself bifurcated, above all by gender. Intermittently in dialogue with ‘herself’ throughout the book, ‘Nathalie’ Stephens’s speaker is overheard talking to and about ‘Nathanaël.’ This alter ego, for lack of a better word—and the language’s lack of a better word says something about our failure to think the idea—is not new to Stephens’s repertoire, having shown up earlier in her 2003 volume Je Nathanaël (Book Thug, 2006). When “I” is Nathanaël, male, the book complains, I am not the female Nathalie. In this way, the self is both doubled and divided: “One of us is a wave,” claims Nathalie/ Nathanaël, “One of us is a shore. It matters little which.” That Stephens writes “l’entre-genre,” as her author’s note (or her authors’ note) specifies, is evident enough: not only is the obvious prose/ poetry overlap in effect, but deeper divisions, or non-divisions, within prose are also on display, as the essay, memoir, and even the récit take turns leading. This fission or fusion of genres is characteristically French, of course, and in Stephens’s case recalls most forcefully Hélène Cixous, who is likewise her forerunner in geographical and sexual alienation. So while Stephens does not share Dickinson’s famous restriction, “They shut me up in Prose,” she does express an excruciating aggravation about being incarcerated by femininity or masculinity. (Stephens’s phrase, “There was a plank of wood and I laid my body on it,” also recalls Dickinson: a plank in Reason broke.) Her entre-genre writing is thus explicitly inter-gender, too—genre is French for ‘genre’ and ‘gender’ alike—and her supplication to “Unletter me” is clearly related to the agony that surrounds being either Nathalie or Nathanaël; each is literally “Lettertorn” from the other, via the minimal difference between “-lie” and “-naël.” (While she neglects to point it out, that ‘genre’ and ‘gender’ are separated by a mere letter is undoubtedly not lost on Stephens, who imbues her text with similar similarities, including “Sutured” and “Stuttering,” “slave (Salve!),” and the trill “cove,” “coveted,” and “Covered.”)

At times the speaker’s (or the speakers’) identity appears to be twofold. The gray half-tones, for instance, install a type of double-talk, whereby the narrator courts or shadowboxes some prior or posthumous, in any case other, self. The volume’s epigraph, from Derrida, sets up this rapport, one interlocutor replying to another, “You’re right, we are undoubtedly several, and I am not so alone as I sometimes say, when the complaint is torn from me and I devote myself, yet again, to seducing you.” Stephens’s rhetoric is itself frequently doubled, such as when she reports that, “The drowned are drowning,” or asks, “Must I defend the maddened against the maddening?” Questions like, “Who do the wounded wound?” open quietly onto problems of tragedy, agency, and abandonment, as in Celan’s lament that no one witnesses for the witness, or Luce Irigaray’s related criticism that in the Hegelian account of Polynices’s interment, no one is left to bury Antigone. Moreover, occasional rhyme intervenes to offset the loss of reason: pairs such as “defeat” and “complete,” “retreat” and “replete,” project their ‘masculine’ status, while “city” and “seditiously” come closer to ‘feminine’ rhyme; the presence of both together furthers the book’s aspiration to partnership. Repetition occurs in The Sorrow And The Fast Of It on the level of the individual letter, as well, reinforcing the broader drive toward coupling, identification. In one early passage, no fewer than a dozen doublings of different letters (b, e, n, o, r, t) happen in about as many ‘lines,’ nearly half of them concerning ‘l’: collapse, billowing, ville, saillie, spiralling. “Bodypart,” the text inveighs, reasserting the bond between corpus and corpus, “Letter by letter. Remove what’s missing.”