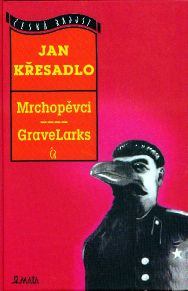

Jan Křesadlo, GraveLarks,Trans.by Václav Z J Pinkava,Jantar Publishing, 2016. [1984.]excerpt

Set in Stalinist-era Central Europe, GraveLarks is a triumphant intellectual thriller navigating the fragile ambiguity between sado-masochism, black humor, political satire, murder, and hope. Zderad, a noble misfit, investigates a powerful party figure in 1950s Czechoslovakia. His struggle against blackmail, starvation, and betrayal leaves him determined to succeed where others have failed and died. This extended edition includes critical texts and analyses with illustrations by Jan Pinkava, Oscar-winning animator. GraveLarks is a fictionalized account of the life of French troubadour poet Villon set in 1950s Stalinist Czechoslovakia. The vagabond and ""bohemian"" Villon is transposed into the vagabond intellectual and ""bohemian"" Zderad. Singing, drinking, deviant sex, and blackmail ensue. The author and publisher Josef Skvorecky described the text as ""the most original, shocking, truthful, and artistically very interesting works of contemporary Czech fiction.""

..."I consider [this book] to be one of the most original, shocking, truthful and artistically very interesting works of contemporary Czech fiction. It is profound, ironic, witty and - what is rare in today's writing - it betrays a learned author, who, in spite of the width and depth of his knowledge, has remained an acute observer of real life and real people. It is not often that one finds, in fiction of any nation, a portrayal of the Stalinist fifties that has been executed with so much freshness, incisiveness, charming cynicism, accuracy... it is also devoid of any sentimental seriousness and it makes excellent reading even for those who are not interested in the political background against which the macabre story is played out. I think that an English-language publication of this novel would be regarded by those who know what literature is all about as a discovery." - Josef Skvorecky

"GraveLarks successfully employs Menippean satire, characterized by a fragmented narrative, frequent shifts of stylistic register and point of view, and the wish to lampoon not so much an individual but a general state of mind (.....) In the bleak world of GraveLarks, criminality and creativity are intimately intertwined" - Andrei Rogatchevski Andrei Rogatchevski, The Times Literary Supplement

“A complex torrent of black humour mixed with rollicking slapstick clowning, of sexual exploitation mixed with warm family love, of sharp, pointed, observations mixed with bizarre and fantastic episodes reminiscent of Meyrink and Kafka.” — John Howard, Wormwood

Not many authors of fiction caution their readers in the narrative: ´...this book is somewhat disgusting in certain parts and this is about to happen now. If you wish you might easily skip this section with minimal damage to your understanding of the plot.....´. Jan Křesadlo does it twice in his masterpiece. In both cases what follows is a display of somewhat embarrassing behaviour of the main protagonists. Křesadlo´s honest and direct contact with his reader is one of the characteristic features of his writing. He wrote Mrchopěvci in Czech during his exile in England in the early 1980s and a doyen of the Czech literature Josef Škvorecký immediately snapped the manuscript up for his exile Czech and Slovak 68 Publishers in Toronto. It was a happy choice because Křesadlo received for Mrchopěvci the highly respected Egon Hostovský Prize in 1984, the same year in which the book came out.

Jan Křesadlo (the pen name for Václav Pinkava) was born in Prague in 1926 and died in Colchester a few months before his sixty-ninth birthday. In fiction he was a late starter, after a vexed as well as varied career in clinical psychology both in Prague and England. I knew him well as an enthusiastic leader of the London Sokol choir and I can say without hesitation that he was a man on the verge of genius in several fields. He had composed music and written essays in the field of logic as well as psychology long before he took up his pen or rather computer to try his luck in fiction. He was also an outstanding poet writing in Czech and classical Greek. Mrchopěvci is a partly biographical story set in Prague of the early 1950´s when Pinkava met his future wife in a church choir. Yet he would deny as he indeed did that he became a victim of politically motivated homosexual blackmail which is described in the book in some detail. The main protagonist, Zderad, is a gifted singer in a small male choir who sing at funerals - hence the title of the book. The behaviour of the individual members of the choir is selfish, materialistic and kafkaesque that when one of them (Tůma) dies, they could not care less where he was buried: ´.....what is certain that he couldn´t have afforded a funeral with singing and his life-long colleagues didn´t consider him worth losing the little money they could earn elsewhere at the time of this funeral....´.

The homosexual blackmail of which Zderad becomes a victim is the leitmotiv of the novel on which Křesadlo illustrates the essentially corrupting influence of Stalinism. It is often the case with the first work of a ´budding´ author that some themes become recurrent even in later works. Such theme in Mrchopěvci is sexual deviation which in fact was Václav Pinkava's specialisation in his field of clinical psychology. This theme reappears in several of Křesadlo´s dozen or so novels and books of short stories.

As a journalist but not a literary critic I can only declare my feelings about Křesadlo´s work and let others pass their professional judgement on it. I admire Mrchopěvci and his work in general immensely for its courage, honesty and mysticism, although I am well aware that Křesadlo has his detractors in print as well. When it comes to putting Křesadlo to some convenient artistic "box", or giving him some useful "label", then I can say that Křesadlo has been described as a "post-modernist" for instance by Karel Janovický, the Plzeň born musician and journalist living in London. Among other convenient labels is "neo-decadence" in the style of Ladislav Klíma. One thing is certain - whatever the "boxes" or "labels", Křesadlo is his own man which I believe could be shown as stemming from his virtual isolation in English exile at a time when he started writing fiction.

Mrchopěvci is the first of Křesadlo´s novels translated by his gifted family into English. The translation is superb, although I find the explanatory notes at the bottom of some pages often intrusive. It would probably be much better if they were placed at the end of the English version. The illustrations by Křesadlo´s Oscar-winning son Dr Jan Pinkava are superb. My favourite is a contour of Stalin´s face in the sky over the Žižkov mausoleum in Prague where the first Communist president Gottwald and one of the most dogmatic Stalinist leaders of all times was resting at the time of the story.

Křesadlo is a phenomenon which will survive many of us. And there can hardly be a better entry of his works into the new millennium than the English version of Mrchopěvci.

I sincerely hope that this is merely a start. - Milan Kocourek

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is always a pleasure to have the opportunity to speak about an author whom I consider to be a literary figure of the 21st Century. His novels and collections of short stories could be concluded with the same words that Stendhal used in closing his The Charterhouse of Parma (La Chartreuse de Parme; 1839) TO THE HAPPY FEW. Jan Křesadlo could also have been sure that his work would be read a hundred years on. Today's happy few who have discovered Jan Křesadlo's comprehensive and exceptional work amid the proliferation of older and contemporary Czech authors, will enter a world which is both demanding and entertaining, a space which is both wise and playful, bizarre and cruel - in truth the very world of our own happiness and anxiety.

When the reader comes up against Křesadlo's works of literature he is beset by a suspicion that he has come up against a phenomenon which has gone beyond the humanly possible, something out of this world. Perhaps Fate has simply played a lighthearted trick by placing so much talent into the being of one man - talent which would have sufficed for a number of successful men, Václav Pinkava, for that is Křesadlo's real name could have been a significant philologist. He had mastered both the written and spoken word of classical Latin and middle Latin, classical Greek, German (which he learnt from infancy at home), and also English, French, Spanish, Italian, but also Hungarian, Romany. Slovak, Upper Lusatian, Russian and Pali. During his student days he enrolled to study Sanskrit under Prof. Lesný, the expert in Europe. For his own purposes he constructed the Urogal language (Fuga Trium) and the Sub-Tuřín dialect (Obětina). He was fascinated by various alphabets - for example he was able to use the difficult Old Slavonic Glagolitic script to write the Czech language. He loved to play on words and this has become a trade mark of his personal style. He could have been a succesful musician. He had the gifts of an absolute ear for music and a superb voice. When, after the purges of February 1948 he became a member of Prague's Catholic semi-underground, his "missa parodica" Spiritus Flat Per Deserta, on the theme of Ježek's Vítr vane pouští, became a popular hit. His novel Vara Guru includes a musical score - Postmaster Kodra's Requiem - his own composition which was performed at the office of the mass for the deceased Václav Pinkava in the old church od Sv. Mikuláš in Vršovice. All his life he was involved in various musical activities, one of these was his experience of the world of funeral singers or "Mrchopěvci", which he describes in such a superb way in his literary debut, the novel which was awarded the Egon Hostovský prize. He was an active musician both at home and abroad. He could also have been a professional logician and mathematician. he was often invited to lecture at international conferences of higher mathematics because of his discovery of a broad class of functionally complete multiple-valued logics, named Pinkava Logics. he was so proud of this feat that it was his wish that the four symbols of the basic functors be carved in the corners of his headstone. He could have been a philosopher - he began his studies at University with this subject. He could have been a professional caricaturist - one who was both biting and witty, pleasant and merciless. One only has to look through the pen and ink drawings which he published in his novels - this time in the guise of illustrator Kamil Troud. he could have been, and in truth he was, an excellent clinical psychologist - both in Prague and in Colchester, where he worked his way up to the position of Principal Psychologist and became an honorary member of King§s College. London University. I personally believe that he could have been a much better literary historian than I am myself - if, that is, he had wanted to spend time on such ephemeral activity.

In the end he went professional with the one talent which I consider his greatest - he became a Czech writer in exile. As an author he remained a personality which was always different, one which withstood outside pressures, one which was received positively or negatively, but hardly ever with indifference. This controversial individualist lived life as a Czech at a time which demanded collective totalitarian assent. In the Czech lands of his birth he chose to take up the position of a solitary outsider, constantly prosecuted but never broken. The first such incident was during the Nazi occupation when he was expelled in his fourth year at grammar school for ridiculing German language teaching. The second time he was expelled from Charles University during the winter semester of 1948/49. It was only by a miracle that he was freed in a trial, naturally a political trial, during which he had been accused of preparing an armed uprising. he only narrowly escaped being conscripted into the notorious "Black Baron" unit. Thanks to an absurd stroke of luck he was able to return to university to study psychology in the 50s - a former employee of his father's business who was grateful that his boss had once paid for his false teeth had become a nomenclature cadre with influence over admissions to higher education. As a graduate Pinkava was only able to take up a position which no one else wanted - in the clinic for sexual deviations. This became a significant experience in his life. As late as 1968 after earlier delays he defended his thesis for the Candidature (the equivalent of a PhD) - which, in line with the Soviet model, was the only "ticket" to a place among experts, a place almost impossible to aspire to from outside the communist ranks - and in the autumn of the same year he emigrated to England, complete with his family.

Pinkava's life is chracteristic of that section of his generation which had never identified itself with the communist vision of a brighter tomorrow. This is the source of Křesadlo's almost obsessive distaste for Milan Kundera's view that the "better half" of the nation enthusiastically joined in the Marxist-Leninist ideology (Kniha smíchu a zapomění) and this is the source of the evaluative expressions "Stalinist Nightingale". He quite justifiably considered himself and those like himself to be the "better half" and this is the point of departure for his works.

His life experience together with his creative inventiveness and extensive reading are the fertile soil from which such interesting work grew. Křesadlo's entry onto the literary scene is marked by a number of handicaps. He made his debut as a prose writer at the age of 58 when others of his generation were already well settled and entrenched in their literary positions. He was an educated traditionalist who felt the link between the wrod art and artisan (n. a skilleed workman; craftsman), he valued the craft of literature - and he was master of it. What is more, he had what I call " the talent to horrify": he saw things as they are, not the way they should be. He knew about strange behaviour in abnormal situations, he wrote of unbridled passions, of the loss of common inhibitions, he was provocative in creating an atmosphere of looseness and the fall of social standards. The World Order is refuted, it turns int grotesque" The apparently closely familiar world is suddenly unmasked as strange and dishonest, the existing sense of direction fails and the curtain rises on the bizarre theatre of reality. Among the motifs of the grotesque are madmen and individuals who are mentally disturbed, there are anthropomorphic monsters, fantastic animals, mutants, in whom the features of various real life creatures are combined.

I would also like to mention a problem which has sometimes caused Křesadlo to be excluded from the ranks of Czech literature - it is the frequent motif of overexposed sex. Tha majority of critics fail to notice that in Křesadlo's work these moments are always a method for parody and radical irony. perversions, ritual sex, the whole palette of sexual deviations are for the author a fundamental metaphor for the failing of tried and tested conservative values and social instinct, a metaphor for barbarism, upheaval and chaos. Křesadlo was a moralist in the best sense of the word. Unusual sexual practices - as he called them - were a tool for ridiculing the semantically empty segments, always the subject of bitter parody. His rejections of cheap sentimental optimism, his distanced sarcasm, his biterness over socierty's rejection of wisdom - these are the reasons why Křesadlo destroys, why he violates the accepted codes of communication with intentional non-conformism. Křesadlo's insane world of fanatics and demagogues is deviant and extreme. The grotesque smashes the universal image of communist progress.

Radical eclecticism is a frequent element in Křesadlo's texts: his own personal experience of life combines with his knowledge stemming from extensive and indepth reading. The result is a text similar to the palimpsest of the Middle Ages. When the scribe scraped the original text off the parchment and then wrote his new text over it, the old text could still be seen behind the new. Similarly, in Křesadlo's works it is impossible to distinguish clearly between the elements of other works of literature and the author's own. The author himself continually comments on this syncretic structure, thus forcing the reader to notice it. he makes him play with meaning, search for it, ponder. Frequently Křesadlo imagines how he himself might have written someone else's text - and sometimes he also does so. For example he had read Fischl's idyll Kuropění and he wrote his own version of the life of the country doctor in the novel Zámecký pán aneb Antikuro.

When the reader enters the bizarre world that is Křesadlo's prose (a total of thirteen books have been published in the period 1984 -1996) he may well at first feel himself buried under a mound of examples of strange behavious in abnormal situations. The deeper he delves into that world, however, the more it will fascinate him. he will be able to appreciate how the wonderful narrative diverges into numerous digressions, how the author both entertains and torments him, and how he tactfully educates him. It is unfortunate that the reader only has access to a small selection of Křesadlo's poetry and that the exceptional translation of Seifert's Věnec Sonetů into English is so difficult to come by.

In conclusion I would like to express my hope -which is supported by the interest shown by my students - that the band of the "happy few" fans of Křesadlo's work will continue to grow and that you will also find your way to enjoy his legacy.

- Dr. H. Kupcová

The literary cultural heritage of Central Europe in the 20th century tends to be associated with a few legendary names: Kafka, Werfel, Rilke, later Canetti or Milosz, and Milan Kundera, who is venerated more abroad than in his native country.

In truth, however, the world of Central European literature, encompassing the century as it draws to a close, is much richer than that and we witness many more inspirational authors, often denied the scope to publish during much of their lifetime, or, having lived and worked in exile, reaching their readership after an uncomfortable delay.

Such writers have paradoxically tended to enter the context of the domestic literary scene as latter-day novices, albeit swiftly acquiring the status of literary classics upon critical review.

In modern Czech literature, just such a living classic storyteller novelist was, until his premature demise, the author Jan Křesadlo (1926 - 1995), whose creative energy covered such areas as poetry, classical philology and music, as well as novel-writing.

He did not publish as a young man, was persecuted during the Nazi occupation of Prague and again after the Communist coup of 1948 and then spent years working at the Prague University Teaching Hospital outpatient clinic for sexual deviations.

After August 1968 Křesadlo opted for exile in Great Britain and settled with his immediate family in Colchester, where he worked as the Head of Psychology at Severalls Hospital. In Colchester, he was known under his own name of Dr. Václav Pinkava, and known for (among other things) his contributions to the theory of Multiple Valued Logics, and for being an active member of the Czechoslovak emigre community in London.

He started writing only in his retirement - whereupon his very first book, a biting political parody of the Czech situation under Stalinism - Mrchopěvci (the title is pejorative slang for Funeral Singers) won him the prestigious Egon Hostovský Literature-in-exile award in 1984.

Jan Křesadlo was more than a mere writer: thanks to his outlook on life and broad range of interests he fully represented The Renaissance Man. From his perspective, his books about the tragic absurdities of civilisation in Central Europe and beyond (in fictitious countries or on an invented planet mimicking Earth) are sarcastic moral tales, holding up a series of distorting mirrors to mankind.

That is not to say that Křesadlo's books are full of moralising lectures to his fellow man or monotonous pleading for moral rectitude: his world-view was, first and foremost, enlightened and knowing, and this artist and thinker harboured not the slightest doubt that this world is not reasonable or wise - that it can even fall prey to its own tendencies to entropy, and is capable of creating forms of society which are anti-life.

The period which Křesadlo experienced at first hand - life in Czechoslovakia during the time of the Soviet political protectorate, the time of political delusions and immense twisting of the moral fibre under power-struggle pressures - is an example of such an absurd social existence.

It was to this theme, this case-history of social co-existence, that the author constantly returned, linking it variously to a political form of sexual deviation, to the period of Satanism in Bohemia, to a time of lost faith and hope. His vantage point was his critical scepticism, his critical faculty, even more critical as more values were forsaken, in particular as mind-science and morality were reaching their nadir beyond Central Europe.

Jan Křesadlo's books are a body of fascinating postmodern parables of European and Czech social circumstances in the latter half of the 20th century, and his thematic excursions into other times and foreign space (something to which he devoted his monumental epic Astronautilia, written in parallel Czech and Ancient Greek verse!) are sarcastic metaphors, illustrating the loss of humanity in a period of history which seems to have entirely lost its sense of direction.

With this view of the world and Man's place within the scheme of things, Křesadlo makes a worthy successor to George Orwell as well as Graham Greene (in particular in his trilogy Fuga Trium) but by contrast we find in his work an incomparably broader palette of genres, ranging from anti-utopian sci-fi (Girgal) through surrealist poetry in prose (Dvacet snů), allegorical poetry satire (Vertikální spílání) right up to a party-piece discourse debunking the false legends of Czech exile (Obětina).

Even where Jan Křesadlo seems to be merely depicting those obscure and bizarre, albeit characteristic aspects of Czech provincial life (e.g. in the novel Vara Guru or in Království české a jiné polokatolické povídky), his effervescent, vivid storytelling is once again a metaphor for the inescapable issues of existence in the modern world.

At the same time he manages to combine a higher plane of universalistic discourse about the world at large with a remarkable empathy for all his figures, of whom he tends to speak with the hint of a smile, putting them in enlightened perspective, which, however, often ends in a wincing grimace.

This peerless creator is only gradually being discovered by Czech literature, but it is clear that literature's future beckons to this exceptional writer and polymath. For the world according to Křesadlo will not go away. Quite possibly, the world will increasingly become Křesadlo's world. - Vladimír Novotný

Czech émigré writer Jan Křesadlo (Vaclav Pinkava), an unexpected interlude in my reading – and another fascinating example of an Eastern European author emerging to prominence after the fall of the literary Iron Curtain - came to my attention by mention of him on a forum concerning literature that contributors wished to see translated into English. In fact, one of Křesadlo’s novels – Mrchopěvci (English title: Gravelarks) – has been translated, in a bilingual Czech-English edition by Mata Press of Prague with black and white illustrations by Křesadlo’s son, Oscar-winning animator Jan Pinkava (two items in this edition that fit my book publishing wish list: attention to binding, with quality paper and a ribbon bookmark, and the courtesy - understandably extendable only to short works - of including the original language version to accompany the translation). Reproduced in the book is a 1987 letter from Josef Škvorecký heaping praise upon the novel - which Škvorecký’s own publishing-house-in-exile, Sixty-Eight Publishers, issued in Czech in Toronto in 1984 - and soliciting interest for an English translation. Alas, it took another 12 years for one to appear, this 1999 Mata edition, which then apparently vanished like a comet. My search of on-line booksellers turned up zero available copies, not even from Mata in Prague, so I was happy to find it in my local library. Gravelarks, a wild, blackly funny work of biting protest and deceptively light-hearted sarcasm aimed at communist rule in Czechoslovakia - “after the year 1948, but still long before the period of the ‘thaw,’ as in so many other émigré novels” - takes its title from the occupation of its main character, an ordinary young nobody named Zderad who, having fallen out of favor with the dominant Stalinist political paradigm, must support his wife and infant son by singing dirges at funerals along with other “gravelarks.” It’s a gray existence, unleavened by the coffin-shaped apartment he inhabits with his family in a grimy part of the city and by the ostracism he experiences as an outcast from the state. But, as the narrator repeatedly observes with Candidean optimism, it still isn’t (quite) “the worst of all possible worlds.” One day after singing for a funeral, Zderad finds himself suddenly plunged into a greater, more nightmarish humiliation when confronted by a tall, pale stranger who produces a photocopy of an anti-Stalinist bit of doggeral Zderad wrote - in Greek - while still a grade school student. Under the oppressive paranoia of the time, however, even such an innocuous little poem would signify “practically a death certificate for its creator,” and the stranger is able to coerce Zderad into a crumbling tomb in the cemetery and subject him to sexual blackmail.

As the blackmailer demands new and increasingly florid encounters, Zderad’s situation is further complicated not only by his diverse attempts to uncover his exploiter’s identity but also by his awareness of a psychosexual power dynamic in which he obtains both profit (he’s paid for his “services”) and an embarrassing element of pleasure:

The cruel mental pleasure of unspeakably obscene power over the horrible blackmailer fused with the sepulchral lover’s revolting but effective caresses, spiced with his muffled sobs and grunts. The posterior of the stinking mandrill, which is incredibly obscene, offends the more sensitive visitor to the Zoo, yet it shines with a symphony of delicate and pronounced hues of greens, reds, blues and purples. Metallic shining flies for example of the genus Calliphora which revel in excrement and carrion, are of a similarly glorious coloration, as are many species of dung beetle. Thus the radiance and glory of Being permeate all its levels. Uninfluenced by the spectacle it was illuminating, the flame of the candle burned with a beautiful and glorious brightness, and, at the same time, Zderad’s lust also flared up in spite of himself. Pulsating, it glowed colourfully with ever greater strength until it finally exploded into a cosmic firework.

The novel follows Zderad’s various attempts to unyoke himself from this sordid exploitation, find inner courage and identity, and rediscover the moment of romantic tranquility and happiness he’d experienced years before when he first met his wife while swimming at a lake in the countryside. Křesadlo’s narrative takes the reader on a picaresque journey through the vicissitudes of Stalinist rule, recounted by a charming, lively, self-interrogating émigré narrator, acutely conscious of his role as storyteller and of his obligation to avoid falling into typical literary pitfalls such as those of the emerging genre of “Easterns,” which of necessity contain “secret policemen, blackmailers, whores and other typical characters” just as “Westerns” contain common elements of “guns, horseriding and the odd bit of cattle ranching.” What results is a freewheeling, anything goes narrative punctuated by bits of musical score and phrases in Greek, propelled with a rocketing narrative velocity that can nonetheless stop on a dime for the narrator to interject his own views or question his own narrative style, even shift gears entirely by suddenly inserting, as an “Intermezzo,” a brief parable in order to more thoroughly (and grotesquely) get across a point.

Křesadlo’s contempt for the communist regime infects the novel at every turn; it’s spiked with scathing references to dogma and institutionalized politics; to the “Youth Unions,” “Joyful Corrective Centers” and other statist institutions with Orwellian names; to the “consumers” who “got out” and turned their backs on those left behind; to acquiescent intellectuals in the West; and in general to the “radishes” (red on the outside, white on the inside) who constituted “most of the contemporary population of Czechoslovakia.” The narrator reserves special scorn for state-supporting intellectuals and for the dreadful state of Czech literature of the time (in a somewhat performative self-interview Křesadlo wrote in the 1990's, his distaste for Milan Kundera was apparent):

…a desert…almost total…the better writers of the future were at that time still in a state of embryonic latency. Some, but not all of them, were writing and publishing true and honest byzantine odes to Stalin, only in the Czech and Slovak languages, of course…

Commenting further on the severity of the literary drought, the narrator notes that the only other books still to be found were those in antiquarian bookshops, “remnants of eliminated ethnic groups” to “be had for next to nothing, because, comrades, who’d want to read them?”

If there’s one element I found slightly bothersome in Gravelarks, it’s Křesadlo’s use of “sexual deviance” as a metaphor for communist corruption (Křesadlo held a degree in psychology and worked for years as a clinical psychologist at the mental hospital affiliated with Charles University, specializing in sexual aberrations). As though there are not already in literature enough homosexual characters portrayed as monsters, Křesadlo appears to go even one better by referring quite simply to Zderad’s exploiter as “the Monster.” But at the same time, the character is so utterly over the top – what starts as a altogether ordinary sexual act blossoms into an astoundingly baroque variety of sexual obsessions and pathologies, both homo-and hetero-sexual, and increasingly monstrous, incorporating even kidnapping and murder – that it’s next to impossible to take him seriously as anything other than metaphor. It’s abundantly clear that by rendering Stalinist communism as a grotesquerie of sordid sexual depravity, Křesadlo mocks the brightly polished, seamless moral certitude of the state’s self-congratulatory self-image. And to be fair, Křesadlo - who, during his lifetime, was instrumental in efforts to decriminalize homosexuality in Czechoslovakia - provides another, far more sympathetic homosexual character as a foil. Still, while this may simply reflect a weariness of such depictions on my part, not to mention the American cultural lens through which I couldn't help but view the book, the device struck me as uncomfortably close to the manner in which, for example, religious fanatics expediently and routinely assign blame for all of a country’s woes to “sexual deviance " (of course, we've all seen what lies beneath that particular brand of polished, seamless moral certitude...).

In the end, though, Křesadlo’s evident talents trumped whatever slight misgivings I had regarding his choice of metaphors. I found myself frequently laughing out loud while swept along by his glittering, barbed, ebullient, acrobatic prose and delighted by the sheer dexterity and breadth of his language, his frequent use of outlandish, comical imagery, and the occasional descriptive gem (i.e. “The sky was as mild as a cow’s eye”). One can only hope that Gravelarks will return to print in English, and that more of Křesadlo’s works will be made available to allow English readers to explore further this remarkable novelist / poet / scholar / composer / linguist / activist. I would be especially interested to see a translation of what is purported to be his magnum opus: “Astronautilia,” an epic science fiction poem modeled after Homer’s “Odyssey,” running to more than 6,500 lines, and written entirely in classical Greek, with Czech translation on facing pages. - seraillonSeven Sparks: an anthology of seven short stories by Jan Křesadlo,selected and translated by VZJ Pinkava

Poetry

https://issuu.com/jantarpublishing/docs/gravelarks_sample

lots more murder). Laurence himself doesn’t appear until the middle of the third chapter; the book instead begins with an account of the perilous peregrinations of a monk, Brother Mocius, through the mountains, during which he drinks brandy, masturbates, and nearly dies several times. While this is frequently presented as a spiritual test, Iliazd also constantly undermines the elevated gravity of these moments with interjections of uncertainty:

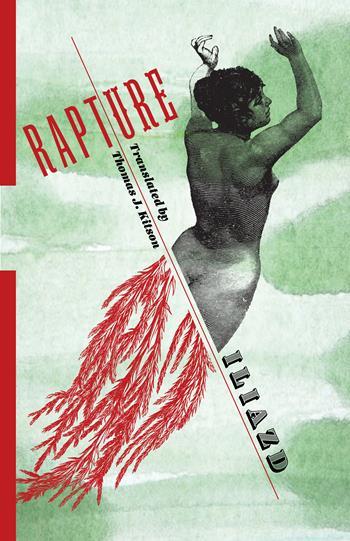

lots more murder). Laurence himself doesn’t appear until the middle of the third chapter; the book instead begins with an account of the perilous peregrinations of a monk, Brother Mocius, through the mountains, during which he drinks brandy, masturbates, and nearly dies several times. While this is frequently presented as a spiritual test, Iliazd also constantly undermines the elevated gravity of these moments with interjections of uncertainty:  Though Rapture is full of spirits and angels it doesn’t occupy any consistent ontological position, as illustrated by the view of Ivlita’s father who is ‘neither a believer nor an unbeliever and thought there were neither angels (evil or good) nor miracles; everything is natural or normal, but there are, so to speak unusual immaterial objects we know nothing about since, for now generally speaking, we don’t know anything.’

Though Rapture is full of spirits and angels it doesn’t occupy any consistent ontological position, as illustrated by the view of Ivlita’s father who is ‘neither a believer nor an unbeliever and thought there were neither angels (evil or good) nor miracles; everything is natural or normal, but there are, so to speak unusual immaterial objects we know nothing about since, for now generally speaking, we don’t know anything.’