László Krasznahorkai, Seiobo There Below, Trans. by Ottilie Muzlet, New Directions, 2013.

excerpt 1

excerpt 2

read it Google Books

Beauty, in László Krasznahorkai’s new novel, reflects, however fleeting, the sacred — even if we are mostly unable to bear it.

In Seiobo There Below we see the goddess Seiobo returning to mortal realms in search of perfection. An ancient Buddha being restored; Perugino managing his workshop; a Japanese Noh actor rehearsing; a fanatic of Baroque music lecturing to a handful of old villagers; tourists intruding into the rituals of Japan’s most sacred shrine; a heron hunting.… Seiobo overs over it all, watching closely.

Melancholic and brilliant, Seiobo There Below urges us to treasure the concentration that goes into the perception of great art, leading us to re-examine our connection to immanence.

A torrent of hypnotic, lyrical prose, Krasznahorkai's novel explores the process of seeing and representation, tackling notions of the sublime and the holy as they exist in art. The chapters are disguised as vignettes, each with its own art form situated in particular time and place. The reoccurring theme of the creation and experience of art provides just enough cohesion to form a philosophical narrative arc. At one point, a visitor of a museum in Venice discovers a painting of Christ that seems to come to life and look back at him with "a sorrow impossible to grasp in its entirety, and entirely incomprehensible to him." Elsewhere, a Noh actor prepares to play Taoist goddess of immortality, Seiobo, by acknowledging that "there is no transcendental realm somewhere else apart from where you are now." Tinged both with sadness and an anxiety about the capability of language, this brilliantly ambitious novel, like the tragic poetry of one of its characters, becomes a "ravishing cadenza" that "cannot be interpreted as anything else but the ceremonial swan-song of a soul sunk into silence."

Nothing vast enters the lives of mortals without ruin - Sophokles, Antigonick, trans. Anne Carson

A Japanese goddess descends to earth in László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below, bearing the fruit of immortality from her heavenly peach tree — but no one notices. She has come to grace the performance of a Noh play that, like Krasznahorkai’s book, bears her name, but though the actor who dances her role has prayed for the opportunity to perform this piece — “I Give Up My Fate Entirely!” — he does not see how his prayer stands manifested beside him.

There are books that, though fantastical, are nevertheless so profoundly continuous with reality that we cease to read them as fantasy. In Krasznahorkai’s breathtaking novel, the sacred exists; Seiobo, who narrates her journey herself, is a fact, just as the actor and the audience are facts. A later narrator offers us the guiding principle of this, our own, reality: amid the “forbidden symmetries” in the halls of the Alhambra, he observes that “something infinite can exist in a finite, demarcated space.” The god is there in the theatre. Seiobo There Below itselfis a finite, demarcated space, but in it something infinite exists.

The latest of Krasznahorkai’s full-length works to be translated into English, Seiobo There Below is a confrontation with the vast, and therefore with vulnerability. In each of its seventeen chapters, the novel describes a process of artistic creation, from the making of Russian icons and the reconstruction of the Ise Shrine in Japan, to the attribution of Italian Renaissance paintings and the carving of Noh masks. Krasznahorkai’s erudition is staggering, but the way he relates the choosing of the wood for the shrine, or the restoration of a canvas, is so attentive and so modest that is sidesteps pedantry entirely, and instead participates in the very concentration it describes. The chapters are numbered according to the Fibonacci sequence, in which each number is the sum of the two before it, and indeed, Seiobo There Below compounds and reinforces itself ever more rapidly, its scope soon defying human proportions.

The artworks Krasznahorkai describes are not only objects, but vessels of a sacred impulse: they are body and soul. The protagonists of the novel —artists, academics, and vagabonds —seek out these works, yearning for transcendence, and are instead crushed by terrifying facts: first, the factof the work’s existence, its material undeniability, and second, the fact of its radical spiritual loneliness. More often than not, the encounter with art and/or the sacred ends in existential disaster. These former channels to the gods have been closed; they have become nearly empty signifiers. In the chapter “Where You’ll Be Looking,” for example, a guard at the Louvre wants nothing more than to spend eight hours a day looking at the Venus de Milo. But he knows that the statue

did not belong here, more precisely, she did not belong here nor anywhere upon the earth, everything that she, the Venus de Milo meant, whatever it might be, originated from a heavenly realm that no longer existed … and yet she, this Venus from this higher realm remained here, left abandoned ….

We do not want the sacred anymore, Seiobo asserts; we have chased it away. But we left a memory of it in these objects, and when we demand something from these memories, we forget that they have the power to destroy us.

The tension between order and chaos has been central to all of Krasznahorkai’s books available in English, Satantango, The Melancholy of Resistance, and War and War. In Seiobo There Below, this tension takes on its most moving and elegant form. Entropy, for Krasznahorkai, is the ultimate destiny of the universe, and art is necessarily in its service. Many characters in the novel are initially attracted by an artwork and the sacred force within it and compelled toward it, only to be overwhelmed by its presence, and then, in the attempt to retreat, paralyzed or annihilated. Some become forces for evil: one chapter is ominously titled “A Murderer is Born”; in another, an artist carves a theatre mask, never understanding that “what his hands have brought into the world is a demon, and that it will do harm.”

The demonic is the shadow of the sacred, and Krasznahorkai does not let us forget it. He is no stranger to darkness; his work is famously bleak. But with Seiobo There Below, he reminds us of an observation of John Berger’s, once made in relation to Goya: “The despair of the artist is often misunderstood. It is never total. It excepts his own work.” In Krasznahorkai’s case, it excepts not only his own work, but also that of countless others, named and unnamed, from both the east and the west. Small, understated gestures throughout the book remind us that it is love, not fear, that drives us to art.

Within the inevitable move toward entropy, Krasznahorkai traces a tiny space of freedom, a tiny path from which to approach the sacred. It requires making the world as small as possible, narrowing the vastness down to just this one brush, this blue pigment, this hinoki wood, this mask and this tool, this ancient way based on ritual and unflinching observation. The successful artists of Seiobo There Below make the space in which the sacred can appear as small as possible, so that it is not deadly yet, so that Seiobo can come and say, “I am not the desire for peace, I am peace itself … do not be afraid.” Seiobo There Below is, in its way, a joyful book.

Even for the most successful of these artists, however, the final result of an encounter with the sacred is non-existence. “Ze’ami is Leaving” is a poignant, beautiful chapter about an ideal artistic creation: one that subsumes the artist into it, making him disappear like the Chinese painter of legend who sailed off into his own landscape. Ze’ami, the most revered figure of the Noh tradition and the author of the original Seiobo play, has been exiled from Kyoto, his home. At some point during his solitary, uneventful days, a poem begins to take shape in his head, and when Ze’ami contemplates the silent hototogisu bird, art and nature finally combine with such harmony that it is as if the poem arises by itself:

hototogisu literally means the bird of time, he tasted the word in this sense, nearly twisting it around — the compound signifying the cuckoo bird is the bird of time — to see from which side it would be suitable to give form to his soul’s deepest sorrows; at last he found the way, and the melody began to formulate itself within him — he was just thinking about it, not calling it by name — and the verse somehow formulated itself like this: just sing, sing to me, so not only you will mourn; I too shall mourn, old old man, abandoned and alone, far from the world, I mourn my home, my life, lost forever.

Ze’ami subsequently turns to prose and writes, essentially, the chapter we have just read. The book that writes itself in our hands is a frequent feature of Krasznahorkai’s work, and here, it allows his own act of creation to join the collection of objects so reverently described, the human archive that will outlast us.

The Ze’ami chapter is followed by one more, number 2584 in the Fibonacci sequence, called “Screaming Beneath the Earth,” in which buried animal sculptures from China’s ancient Shang dynasty screech for all eternity against the “earth-demon” that crushes them and that will one day crush all of us. This brief, disturbing final episode, with its characterization of China as endless and immeasurable, clearly recalls Kafka. But in its tight, coiled fury, it is also reminiscent of Krasznahorkai’s own Animalinside, a collaboration with the German artist Max Neumann (published in English before Seiobo There Below but in Hungarian after):

and before their cataract-clouded bulging eyes there is not even one centimeter of space, not even a quarter-centimeter, not even a fragment of that quarter, into which these cataract-clouded bulging eyes could stare, for the earth is so thick and so heavy, from all directions there is only that, everywhere earth and earth, and all around them is that impenetrable, impervious, weighty darkness that lasts truly for all time to come, surrounding every living being, for we too shall walk here, every one of us…

FinishingSeiobo There Below is like walking out of a cathedral: its parting gift is a ringing in the ears. This book is magnificent and will outlive interpretation.

*

Krasznahorkai’s English readers are doubly fortunate this year to have not only Seiobo There Below, but the arts magazine Music & Literature, whose superlative second issue was devoted to Krasznahorkai, Max Neumann, and the filmmaker Béla Tarr. “Ze’ami is Leaving” appeared there several months before the novel was available, accompanied by a selection of Krasznahorkai’s short stories, speeches, and interviews, all previously unavailable in English, and all as bewitching as his novels.

Of particular interest are the commentaries by Krasznahorkai’s translators. George Szirtes’ essay “Foreign Laughter: Foreign Music” describes his process of translating Krasznahorkai for the first time. The translator of Seiobo There Below, Ottilie Mulzet, whose challenges must have been enormous and whose results are miraculous, gives a brilliant interview in which she explains Krasznahorkai’s relationship to Asia and shares her own insight into his work.

Additionally, Music & Literature provides translations of reviews and essays by French, Hungarian, and German critics, as well as original pieces by Anglophone writers. Though the issue is mainly devoted to Krasznahorkai, Béla Tarr is considered in an essay by the Argentinean writer Sergio Chejfec, and Max Neumann is given due praise in a spectacular essay by Dan Gunn, who edits the Cahiers Series that published Animalinside. The volume makes an impressive addition to Krasznahorkai scholarship in English, and will no doubt remain an invaluable resource to his readers for years to come. - Madeleine LaRue

The fiction of Hungarian writer László Krasznahorkai is often called “obsessive” by critics. For good reason—his sentences are enormous and repetitive, and his subjects are rigorously examined from all angles. He is a master of the breathless paragraph, the hypnotic meditation. James Wood, in a piece about Krasznahorkai’s pull as a postmodernist, noted that the worlds conjured by Thomas Bernhard seem more logical by comparison. Reading the Hungarian, he said, “is a little like seeing a group of people standing in a circle in a town square, apparently warming their hands at a fire, only to discover, as one gets closer, that there is no fire, and that they are gathered around nothing at all.” This is a colorful image that the latest of Krasznahorkhai’s novels to be translated into English might be seen as refuting. Krasznahorkhai’s subject in Seiobo There Below is the motivations and the machinations behind beauty in art. Why bother with perfection, why seek it? How do we get there? Kraznahorkhai weaves together narratives that look at the connection between people and what they produce. In one plot thread, he looks at a Japanese Noh actor practicing; in another, he writes about a painting that is actually inhabited by Jesus Christ. Each chapter is related thematically and, as the jacket copy is eager to point out, is arranged according to the Fibonacci sequence of integers, which is to say that this is a novel with a method beneath its madness. Seiobo There Below is an excitingly smart and inventive novel, but it’s moving, too. It is difficult to cite particularly moving moments out of context (such is the spell of a book that flowers like an artichoke), because you often don’t know how you got to the feelings you’re having while reading about, say, a reconstruction of a sculpture of the Buddha, or young people discussing The Clash. Krasznahorkai is an expert with the complexity of human obsessions. Each of his books feel like an event, a revelation, and Seiobo There Below is no different. - www.thedailybeast.com/Hungary has been in the news these past few years for all the wrong reasons. Its government, led by the right-wing nationalist Viktor Orban, has been curtailing civil liberties and cracking down on cultural freedoms, much to the chagrin of other European leaders. It's ironic, then, that at this troubling moment for Hungary, a generation of talented writers has been winning more attention abroad. The Nobel Prize winner Imre Kertesz, author of the new memoir Dossier K, and the polymath Peter Nadas, whose giant novel Parallel Stories was a publishing event, are probably the most famous Hungarian writers working today. But increasingly, young American literary types are falling for an unlikely Hungarian icon: Laszlo Krasznahorkai, a novelist and screenwriter whom the late Susan Sontag once called "the contemporary master of the apocalypse."

"Why is New York's literary crowd suddenly in thrall to Hungarian fiction?"The Guardianasked last year when the writer came to the United States. That may have been an overstatement, but it's true that Krasznahorkai writes unlike anyone else in fiction today, and something about his powerful, unsettling fiction drives fans to excess. His latest book to appear in English is Seiobo There Below, first published in Hungary in 2008. This newest novel — or maybe it's a book of interrelated short stories; the chapters connect only in tangential ways — is an excellent introduction to Krasznahorkai's difficult but deeply rewarding fiction. Brighter and more open than some of his earlier works, Seiobo is a book about art, about artists and spectators, the difficulty of artistic creation, and the glorious, sometimes overwhelming force works of art can have upon us.

In each chapter (or story), set in locations as far afield as Venice and Kyoto and in periods from prehistory to today, we encounter artists struggling to create beauty amid the pressures of daily life, and ordinary people striving to concentrate on works of art against the roar of the world outside. In one section, a homeless Hungarian man wandering in contemporary Barcelona wanders into an apartment building designed by Gaudi and finds himself overcome by an exhibition of Russian icons, "terrifyingly shining and golden." In another, an old craftsman painstakingly carves masks for a Noh theater company; the labor is peaceful, but the result is demonic. Many of the artists and cultural figures Krasznahorkai follows are real, such as the Italian painter Perugino; others are fictional, and still others hover on the border between the two. The link among them — if there is one — is the goddess Seiobo, a figure of Japanese mythology who makes occasional appearances throughout the book. In a rare moment of first-person narration, Seiobo descends from the heavens to inspire a theatrical performer, and themes of the sacred and profane reoccur in other chapters; perhaps she is there too.

The breadth of material these stories cover is breathtaking, but Krasznahorkai wears his erudition lightly. Seiobo There Below proceeds slowly and deliberately, building up from page to page until each chapter obtains an almost unbearable intensity. His characters are usually isolated, in studios or ateliers, and where other authors rely on dialogue, Krasznahorkai relies abundantly on third-person narration. He constructs portraits out of minutely observed details and places them into surprising, sometimes cosmic settings.

Near-infinite sentences in a nonlinear narrative shuttling across time and space, linked only by occasional appearances from a Japanese goddess? It sounds daunting, I realize. Yet the amazing thing about Seiobo There Below is that Krasznahorkai makes the whole thing feel utterly natural and utterly relevant. Krasznahorkai is one of contemporary literature's most daring and difficult figures, but although this book is ambitious, it isn't ever obscure. On the contrary: it places upon us readers the same demands of all great art, and allows us to grasp a vision of painstaking beauty if we can slow ourselves down to savor it. - Jason Farago

There was a time when, as a Romanian poet once put it, every rotten tree trunk held a god. In Seiobo There Below (Seiobo járt odalent, 2008), László Krasznahorkai reminds us repeatedly that this time is long past. Not only is the sacred in retreat from the world, but we have forgotten how to perceive it (two sides of the same coin, some might say)[1]. And yet the fifty-nine-year-old Hungarian author persists in speaking of transcendence. For Krasznahorkai, the spirits that once conveyed mystery and authority have not completely withdrawn; traces of the divine may still be discerned in the making and receiving of tradition-bound forms of art. Seiobo There Below represents seventeen remarkably diverse and ambitious forays into aesthetic grace.

Seiobo is the fifth of Krasznahorkai’s sixteen books to appear in English. The fact that his other major novels in English translation – The Melancholy of Resistance, War and War, and Satantango– have primarily been set in Eastern Europe makes this latest effort seem like more of a departure than it actually is. A large part of the North American perception of Krasznahorkhai as “the contemporary Hungarian master of the apocalypse” (as Susan Sontag famously labeled him), has to do with the epic film adaptations of Krasznahorkai’s work that he and his friend director Béla Tarr have collaborated on (Damnation, Sátántangó, Werckmeister Harmonies), as well as the order in which the author’s books have appeared on these shores (his first novel, Satantango took 27 years to make it into English). As Seiobo’s translator Ottilie Muzlet has pointed out, Krasznahorkai’s Hungarian readership would be aware of the fact that the years 1999-2008 marked a transitional period in his work, which saw him turning increasingly to the Far East for inspiration.[2]

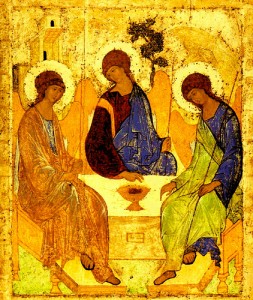

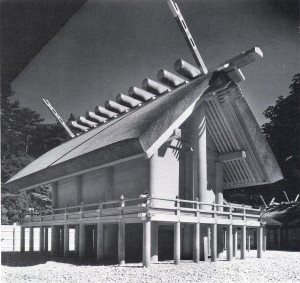

Fittingly then, the original Seiobo is a work of fifteenth century Japanese Noh theatre, in which the titular goddess comes down from heaven to the earth below, bearing immortality. While the character Seiobo appears in one chapter of Krasznahorkai’s latest work, and Noh theatre pops up in a handful of others, the title Seiobo There Below describes more generally an arc that recurs in a variety of locations and tonal registers throughout the book’s seventeen sections. Each chapter presents an intersection (or failed intersection) between the sacred and the human, the immortal and the perishable, via aesthetic production and/or reception. Krasznahorkai alternates between Europe and Asia, ranging across 3000 years of cultural history, featuring familiar works such as the Alhambra, the Acropolis, and the Venus de Milo, but also a 500 year-old copy of Andrei Rublev’s Trinity Icon, the restoration of a Buddha sculpture, and the rebuilding of Japan’s Ise shrine.

In the book’s first section, entitled “Kamo-Hunter,” the object of aesthetic contemplation is a white bird standing in the middle of Kyoto’s Kamogawa river:

A bird fishing in the water: to an indifferent bystander, if he were to notice, perhaps that is all he would see—he would, however, not just have to notice but would have to know in the widening comprehension of the first glance, at least to know and to see just how much this motionless bird, fishing there in between the grassy islets of the shallow water, how much this bird was accursedly superfluous; indeed he would have to be conscious, immediately conscious, of how much this enormous snow-white dignified creature is defenseless—because it was superfluous and defenseless, yes, and as so often, the one satisfactorily accounted for the other, namely, its superfluity made it defenseless and its defenselessness made it superfluous: a defenseless and superfluous sublimity; this, then, is the Ooshirosagi in the shallow waters of the Kamogawa, but of course the indifferent bystander never turns up; over there on the embankment people are walking, bicycles are rolling by, buses are running, but the Ooshirosagi just stands there imperturbably, its gaze cast beneath the surface of the foaming water, and the enduring value of its own incessant observation never changes, as the act of observation of this defenseless and superfluous artist leaves no doubt that its observation is truly unceasing…

Vision is crucial in Krasznahorkai’s work. Even in the sad and hilarious thirteenth section, the sole chapter of Seiobo There Below to focus on sound, the visual trumps the aural when a failed architect delivers a hysterical lecture on Baroque music to a group of elderly villagers who cannot take in the man’s words, because “it was really his gut that captured the attention of the locals, because this gut with its three colossal folds unequivocally sent a message to everyone that this was a person with many problems….” In the Kamo-Hunter chapter, however, the white bird serves a dual function. If it were enough just to see this bird in the river, then the initial clause, “A bird fishing in the water,” would suffice. The bird is a living work of art, but Krasznahorkai also grants the creature “the artist’s powers of observation,” so that it possesses the very powers of aesthetic perception that the prose displays. From the outset, Krasznahorkai suggests that perceiving the sublime is going to take more than simply looking as we are accustomed to doing (though the indifferent bystander is incapable even of this).

In The Senses of Modernism, Sara Danius reminds us that, “The etymological meaning of ‘aesthetics’ springs out of a cluster of Greek words which designate activities of sensory perception in both a strictly physiological sense, as in ‘sensation,’ and a mental sense, as in ‘apprehension.’” The indifferent bystander never turns up, but there is at least one person who perceives the Kamo-Hunter with an etymologically faithful aestheticism bordering on obsession: our narrator. In this opening chapter, Krasznahorkai caresses his white bird in mesmerizing, exhaustive prose, returning to it again and again as he weaves his way through modern day Kyoto, the “City of Infinite Demeanor.” The above sentence continues for another half-page and is by no means one of the lengthier ones in the book (in defense Krasznahorkai’s long sentences, the man knows how to wield a semicolon). It is as if the author is attempting a feat of linguistic perception to rival the bird’s “truly unceasing” gaze of “enduring value.” This heroic effort ensures that, in a delicious paradox, even those chapters that present failed intersections between the sublime and the human enact a level of writerly attentiveness that approaches transcendence.

Let us note one further thing about this opening chapter: an adjective attached to the word beauty. “The bird is granted the artist’s powers of observation,” we are told, so that it may represent “unbearable beauty.” For Krasznahorkai, immanence is a terrifying proposition. Few of the encounters with the aesthetic sublime in this book lead to healing, redemption, or acceptance. In a later chapter, a migrant Hungarian labourer’s unintentional encounter with a Russian icon painting leads him to purchase a large, sharp knife. Given the volatile power of art, why would anyone desire to commune with it as intensely as Krasznahorkai and some of his characters do?

Desire itself is commonly held to be the engine of the novel. It is important to remember that Seiobo is a novel, albeit one that at first glance appears to unfurl beneath an entirely different logic. For starters, the chapters are structured according to the famous Fibonacci sequence, and vary in length from eight to forty-eight pages. In the absence of a single main character, one way to connect Seiobo’s episodes to a central longing is to consider what Krazsnahorkai has said previously about his writing, that the sentences “are really not mine but are uttered by those in whom some wild desire is working.” In this sense, the most obvious desire at work would be the Bernhardian compulsion to continue speaking, narrating breathlessly before that final end stop, death, is imposed.

Yet there is another, more commanding form of desire in Seiobo There Below. In a recent essay, Scott Esposito identifies in Krasznahorkai’s writing the aspiration to an “authority beyond the physical confines of our universe as we know it.” Is there another living novelist of whom this could be as convincingly said? Krasznahorkai’s search for this level of authority allies him with the high modernism of Joyce and Rilke (think Stephen Dedalus’s artist-God merging with the terrible angels of the Duino Elegies), and it may also be the driving force behind his search for transcendence in the process of making and receiving of art. There is a fine line between wanting to know God and wanting to be God, a fact which Krasznahorkai is well aware of, and exploits to his advantage. Esposito: “Modernism attempts to conflate the aesthetic with the religious.” Indeed.

The modernists’ desire for mastery has often been linked to the waning of traditional sacred structures in the West. In Seiobo, the European forms have long since been displaced, and it is only in Asia that we find contemporary cultures still connected to living traditions. Fredric Jameson has written that “Modern art drew its power and possibilities from being a backwater and an archaic holdover within a modernizing economy: it glorified, celebrated, and dramatized older forms of individual production which the new mode of production was elsewhere on the point of displacing and blotting out.” Certainly, on one level, this is precisely what Krasznahorkai is engaged in. But notice Jameson’s tense: Modern art drew. This quotation comes from Jameson’s Postmodernism: The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, published in book form in 1991, when Modernism and its concerns were considered passé. What then is Krasznahorkai up to? Is he merely inhabiting an unproductive nostalgia for the past? Why can’t we shake our desire for wholeness? Perhaps, as Gabriel Josipovici has argued persuasively, Modernism’s concerns need to be understood not as belonging only to a particular era, but “as the coming into awareness by art of its precarious status and responsibilities, and therefore as something that will, from now on, always be with us.”

This is ultimately the reason why a book that examines the notion that the divine inhabits certain aesthetic objects can feel both epically, off-the-radar strange, and at the same time perfectly relevant. That Krasznahorkai successfully traces this inexplicable presence through a sixty-four clue Italian language crossword puzzle, the making of a Noh mask, and across a twenty-three page single sentence essay on the mysteries of the Alhambra is evidence of an astounding ambition and mastery. Here we are solidly in the realm of what Steven Moore would call “the novel as a kind of delivery system for aesthetic bliss.”[3]

But Krasznahorkai doesn’t just dazzle, he terrifies. By the final chapter, Seiobo There Below has accumulated a horrifically beautiful, almost unbearable force.

Writing about William Golding’s Pincher Martin, Josipovici notes that the traditional purpose of fiction is to protect us from the reality of our deaths. Krasznahorkai strips this protection away. The reality of death is often close at hand in Seiobo; many of the encounters with art bring a sharp awareness of mortality. For Krasznahorkai, the mystery of art is the closest thing to truth that we can glimpse, aside from death. (Perhaps it is no coincidence that these days we have less and less attention to give to either). At the end of the Kamo-Hunter chapter, our narrator advises his bird on the wisest course of action:

It would be better for you to turn around and go into the thick grasses, there where one of those strange grassy islets in the riverbed will completely cover you, it would be better if you do this for once and for all, because if you come back tomorrow, or after tomorrow, there will be no one at all to understand, no one to look, not even a single one among all your natural enemies that will be able to see who you really are; it would be better for you to go away this very evening when twilight begins to fall, it would be better for you to retreat with the others, if night begins to descend, and you should not come back if tomorrow or after tomorrow, dawn breaks, because for you it will be much better for there to be no tomorrow and no day after tomorrow; so hide away now in the grass, sink down, fall onto your side, let your eyes slowly close, and die, for there is no point in the sublimity that you bear, die at midnight in the grass, sink down and fall, and let it be like that—breathe your last.

It is possible, of course, that art will one day no longer be with us, but it is more probable that we will no longer be with art. When there is no one left who knows how to perceive a work, then it may well as crawl off and die, like the white bird that opens Krasznahorkai’s book. But we have not reached this point yet. Against the odds, making and perceiving continue. – Eric Foley

Seiobo There Below begins with a bird, a snow-white heron that stands motionless in the shallow waters of the Kamo River in Kyoto with the world whirling noisily around it. Like the center of a vortex, the eye in a storm of unceasing, clamorous activity, it holds its curved neck still, impervious to the cars and buses and bicycles rushing past on the surrounding banks, an embodiment of grace and fortitude of concentration as it spies the water below and waits for its prey. We’ve only just begun reading this collection, and already László Krasznahorkai’s haunting prose has submerged us in the great panta rhei of life—Heraclitus’s aphorism that everything flows in a state of continuous change.

But the chapters of Seiobo There Below are not really independent stories; rather, they form a precisely composed sequence of illuminated moments that are interconnected in many complex ways. Of these, “Kamo-Hunter” is the only one that does not describe a process of artistic creation, but a bird’s (and by implication the narrator’s) power of focus, the heightened state of awareness necessary to stem itself against the wind and resist the pull of the current to remain perfectly still until the moment arrives to snatch up its prey. And suddenly it’s less a matter of the ceaseless movement of all things, but of absolute composure, a deepest possible being in the present tense, a kind of timelessness in which the moment and eternity conjoin to create a brief flash of transcendence. It is about “one time, immeasurable in its passing, and yet beyond all doubt extant, one time proceeding neither forward nor backwards, but just swirling and moving nowhere.” This, in short, is the nature of the concentration required to create art—and what makes “Kamo-Hunter” such a cogent opening to this novel.

After the publication in English translation of Satantango,The Melancholy of Resistance, and War and War—which together with Seiobo There Below constitute an important cross-section of Krasznahorkai’s prodigious literary output—his bleak outlook on a human history bent on calamity has become legendary. In an interview published in 2012, he expresses doubt that the human race will survive another 200 years. Regarding our collective ability to alter this course, his prognosis is less than optimistic as he calls the authority of literature itself into question: “This kind of communication is really over and done with. Its disappearance is a rather obvious process; it is happening faster at some points of the world than at others. I’m afraid this kind of literature is not sustainable.” To compound the matter, as the incessant onslaught of information fragments our attention on a daily basis, it has to be said that reading Krasznahorkai is not particularly easy, even given the seductive nature of his prose. Moreover, with Seiobo There Below, he has set himself the task of writing about something that is essentially impossible to formulate in language. We are no longer accustomed to using words like “illumination,” “transcendence,” or “epiphany”; indeed, in our secularized Western world they can sound embarrassing and even ridiculous. Yet his is a language that flows in liquid state, eddying around obstructions to form vortices of swelling thought in which the consistency can suddenly gel, become viscous—and all at once, the writing embodies precisely what it describes as these endless, spell-binding sentences gradually alter our perception and prepare us for a brief glimmer of something outside ourselves, something that can perhaps explain us to ourselves.

Seiobo There Below is a novel comprised of seventeen chapters numbered according to the Fibonacci series, by which each consecutive number is the sum of the two preceding it. And indeed, in a larger sense, each section seems to be part of a hidden pattern that expands in an unexpected manner. The series, which describes the progression of the spiral, the unfurling of a fern, the arrangement of leaves on a stem, and countless other natural sequences, quickly accretes from 1 to 2,584, the number given to the book’s seventeenth chapter. There is, however, a small but significant difference here: perhaps in light of the ontological quandary the leap between nothingness and one implies, Krasznahorkai has not begun his collection with zero.

The subject matter expounded upon in this book ranges from Eastern aesthetic and religious traditions such as Japanese Noh theater and the Shinto rituals governing the rebuilding of the Ise Shrine every twenty years to Byzantine icon paintings; Baroque music; works of the Italian Renaissance; and the mathematical mysteries of the Alhambra and their links to crystal formations, “forbidden symmetry,” and the tessellations of Penrose tiling. There is nothing postmodern about this whatsoever; Seiobo There Below is anything but an accrual of arcane information or a piling up of cultural artifacts. As Krasznahorkai patiently enumerates the many consecutive steps of a process of artistic creation in lengthy excursions on handicraft and religious ritual, we are called upon to negotiate the distance between the wealth of historical material and the deluge of foreign terms this book supplies, and the Zen-like focus required to comprehend the transcendent states the rarefied aesthetic and religious traditions he describes invoke. There are numerous parallels in motif throughout the book’s individual chapters, among them the nature of authorship and the original, the complicated ramifications of restoration, and the history of a work’s reception, to name but a few; more than anything, however, this is a book about the sacred—and its embodiment in some of the most compelling works of art human civilization has produced in recorded history.

As the mystic Simone Weil observed in her meditations on faith,

If sometimes a work of art seems almost as beautiful as the sea, the mountains, or flowers, it is because the light of God has filled the artist. In order to find things beautiful which are manufactured by men uninspired by God, it would be necessary for us to have understood with our whole soul that these men themselves are only matter, capable of obedience without knowledge.In other words, the beauty of the divine can pass through them and manifest itself even when they are “sleeping.” Seiobo There Below describes methods of artistic handicraft so rich in tradition and so highly ritualized that the full conscious participation of the acting agency, that is, the person or persons physically doing the work, is not entirely necessary. It’s not a matter of personal creative expression or vision, but the sense of the artist as conduit, a vessel through which a meaning far larger than the artist’s individual understanding passes from a higher source. Painstaking descriptions of elaborate preparatory rituals abound; the vessel must be purified, the caldron must be turned upside down and emptied of its contents before it is worthy of holding the sacred meal. Approaching this process from a far less mystical perspective, the phenomenologist Mikel Dufrenne wrote that “even if meaning is not constituted by man, it passes through him. . . . But it may not be enough to say that nature is expressed by the artist. Perhaps we should rather say that it is by means of the artist that nature seeks to express itself.” Creative activity, then, requires a removal of the self, a minimizing of interference on the part of the ego to maximize human receptivity to a natural or divine truth that is then expressed in an aesthetic form accessible to human perception.

Needless to say, Seiobo There Below is a work of metaphysical content. Just as the first chapter is the only one not to be told from the point of view of a maker or viewer of a work of art, “The Life and Work of Master Inoue Kazuyuki” is the only one narrated, in part at least, from the perspective of a deity. During a performance of traditional Japanese Noh theater, the goddess Seiobo leaves her heavenly realm to descend to Earth and inhabit the actor on stage:

you have to know that your own experience in this is crucial . . . for everything occurs in one single time and one single place, and the path to the comprehension of this leads through the correct understanding of the present, one’s own experience is necessary, and then you will understand, and every person will understand that something cannot be separated from something else, there is no god in some faraway dominion, there is no earth far from him here below, and there is no transcendental realm somewhere else apart from where you are now, all that you call transcendental or earthly is one and the same, together with you in one single time and one single space . . .As the mind ceases to search for something outside itself, time stands still: it is this moment of comprehension, this encounter with immanence that Krasznahorkai approaches again and again throughout the novel.

And again and again, the world foils this endeavor. The distance between everyday life and the sacred is vast. Many of the profoundest masterworks of the past required prayer and ritual to prepare for their creation; these did not merely fulfill a symbolic function, but laid the ground for the divine to enter physical matter in a very real, theophanic sense. Belief is the essential prerequisite, and when the self is deemed not worthy enough to act as a channel for manifestation, the failure can spell disaster. In “A Murderer is Born,” Dionisy, the Byzantine master commissioned to paint a copy of Andrzej Rublev’s famous Troika—not, that is, a copy as we understand it today, but an identical work consecrated upon its completion by a bishop and thereby acknowledged as genuine—has fallen prey to self-doubt,

for surely Dionisy knew better than anyone else that if the soul did not feel what Rublev did in that time, then he himself would certainly end up in Hell, and the copy would come to nothing, because it would be just a lie, a deceit, a mystification, just an ineffectual and worthless piece of trash, which would then be placed in vain in the Sovereign Tier of the church’s iconostasis, in vain would it be placed there and worshipped, it would not help anyone and would only lull them into the delirium that they were being led somewhere.Conversely, as painstakingly described in “The Preservation of a Buddha,” a lengthy and intricate ceremony must be performed to divert the divine light from the eyes of the Amida Buddha statue of the Zengen-ji Monastery to permit its being transported for restoration. The day the Hakken Kuyo ritual is to commence, the abbot gives the order for the monastery gates to be closed; there are countless prayers to be chanted, the musicians must perform at exactly the right moment, there is the Incense-Lighting Hymn, the Invocation, the Triple Vow, the greeting of the Zengen-ji Bodhisattva, the Prayer of the Sangharama. The temporary removal of the gaze from the Buddha’s eyes constitutes the deepest meaning of a secret ceremony many of the participating monks are not even privy to. When the Buddha arrives at the National Treasure Institute for the Restoration of Wooden Statues in Kyoto, the master informs his workers that they are holding this divine gaze within their souls as they individually labor over the conservation of the dismembered statue. One year later, upon the Amida Buddha’s return to the monastery, the ritual for restoring the divine light to the statue is even more elaborate than the first; it signifies nothing less than a renewal of faith, a prayer that “this treasure-laden throne shall be resplendent until the end of time, when the body itself shall vanish, and that the light between the Buddha’s eyebrows may once again issue forth, and that one ray of this light may spread across the entire Realm of Dharma.”

Each part of Seiobo There Below revolves around an encounter between the sacred and the profane. Often, the character whose lot it is to experience a manifestation of the immaterial has not only not been seeking it, but is horrified by the experience, forced to flee from it. In “A Murderer is Born,” the Hungarian drifter stranded in Barcelona who has wandered by chance into an exhibition of Russian icon paintings reluctantly stops before Dionisy’s Troika, as though summoned by its three winged figures. He is afraid to look at them, and when he does, he suddenly understands, dumbstruck, that they are real. Yet they do not bring him salvation or grace, but delirium; they are the annunciation of his demise.

This is one of many parallels Krasznahorkai constructs throughout the novel. Although the drifter is in need of a miracle to save him from his hopeless situation, he is persecuted by the vision he has. The fatal dissonance that marred the creation of the work of art meets with a corresponding dissonance in its reception. It is as though Dionisy’s crisis of faith had imbedded itself into the painting centuries before and remained there, waiting for the drifter—as though the two were indissolubly bound together. Furthermore, Casa Milà, the opulent building housing the exhibition, is an apt setting for the encounter: Gaudí, a devout Catholic, had considered abandoning the project when he was prevented from adding the statuary he’d planned to integrate into the structure, which included Our Lady of the Rosary and two archangels. Against the convictions of his faith, he was nonetheless persuaded by a priest to carry the work to conclusion. Krasznahorkai proposes the notion of art and the artwork as the dispatcher of a curse, whereby wavering belief and the mishandling of aesthetic power necessarily lead to destruction and ruin.

Although not always on this order of magnitude, the relationship between the creation and reception of a work of art in Seiobo There Below is invariably tense and mysterious. In the best sense, we are pilgrims; in the worst, tourists. The visitor to Venice in “Christo Morto” finds himself in an embarrassing position: to allow the soles of his black leather oxfords to last longer, he has fitted them with metal taps that cause his footsteps to resound deafeningly in the afternoon siesta silence of Venice’s narrow alleyways. He has come to revisit a single building, the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, and his purpose prompts him to set himself apart from the ordinary tourist: “He was not one of those who kept coming back here again and again, in pursuit of so-called illusory pleasures, giving himself over to the blank drift of superficial and frankly idiotic raptures—he was not in any way like one of them!?” Eventually, his conspicuousness gives way to paranoia: he imagines he is being followed by a stranger with an odd, S-shaped body, a kind of serpent that symbolizes the city itself:

he did not love Venice, he was instead afraid of it, the way he would be of a murderously cunning individual who ensnares his victims, dazing them, and finally sucking all the strength from them, taking everything away from them that they ever had, then tossing them away on the banks of a canal somewhere, like a rag . . .The traveler’s journey to see a particular painting, one that holds deep personal meaning for him, becomes a kind of perilous odyssey he barely survives.

Similarly, in “Up on the Acropolis,” a visitor to Athens makes his way through the scorching heat and maddening traffic of midday Athens, all the way from Syntagma Square through the Plaka, on foot, to behold, in person, what he has dreamed of seeing for his entire life: the Parthenon, the Propylaea, the Temple of Nike, the Erechtheion. He has forgotten to bring water with him; more importantly, he has forgotten sunglasses. Still optimistic before ascending the hill, he eventually succumbs to despair when the blisters on his feet and the inability of his eyes to adjust to the dazzling sunlight glaring off the white limestone ground render him unable to see anything at all: “ . . . like a blind man, he felt the path before him with his foot, as it was utterly impossible to look up by now, just as it was even to glance upwards, tears rolled down from both of his eyes . . . he then understood that what he had come here for would remain forever unseen by him . . . ” The implication is that it’s not merely his actual eyesight that is failing him, but his innate ability to absorb a cultural and religious truth that has already receded beyond the point of intelligibility.

Throughout this novel, the sacred has either grown indecipherable, has turned into something too powerful for the modern world, or has vanished altogether, having understood that it is obsolete and unwanted. When the man in “Christo Morto” revisits a painting of Christ he has seen only once before, he undergoes a profoundly disturbing experience. Throughout the entire day he has been haunted by an article he read that morning in La Corriere discussing the papal position on heaven, hell, and purgatory; he has learned that Benedict XVI, in contrast to John Paul II, regards hell not as a symbol or metaphor, but as something physically real. The newspaper headline—“HELL REALLY EXISTS”—hounds him. And staring now at this painting of Christ, whose eyes begin to open in profound, boundless sorrow, he understands that the true meaning of Hell is not the mere damnation of the individual soul, but an actual withdrawal of God from the world.

Ottilie Mulzet, who has translated Seiobo There Below expertly into English, has observed:

part of the power of these narratives is that they explore the sacred—or rather the complete and total lack of the sacred in the present time through the lens of all these different cultures. And the answer is always the same: we have lost touch with it, we don’t want it, we have become too weak to bear it, or that the sacred itself, abandoned for all time, just wants to disappear.If Krasznahorkai is saying that the relationship to the divine through art is on the brink of extinction, this book would essentially be a modern tragedy about the failure of civilization to redeem humankind and hence both an affirmation of the sacred and the simultaneous announcement of its demise. And because this is Krasznahorkai, there is the undeniable, brooding sense that the world is coming to a shabby and unspectacular end that makes for a rather pitiful apocalypse of the blind, amnesiac, numb, and brutal.

But there is also a bleak humor running throughout the book, and the impossible figure of a hobby lecturer on baroque music in a village library can be seen as a parodic self-portrayal as well as a tribute to the elderly apodictic protagonist of Thomas Bernhard’s novel Old Masters. While Krasznahorkai’s prose recalls Bernhard in certain obvious ways, and the two have been frequently compared due to their exasperatingly long sentences, or their spiraling syntax, this is where the comparison ends. Bernhard’s vehicles are rant and invective; Krasznahorkai’s is compassion, the actual identification with the suffering of another. His characters are invariably outcasts, untouchables society has expelled—and for good reason. His compulsion is to plumb the soul of the pariah to tap into the inscrutable darkness at the heart of the universal human condition.

Seiobo There Below is a profoundly European book. In a certain sense, it is a farewell to the Occidental world as it has endured in a cultural counterbalance with the Orient. It is also a last look at the West in the eyes of an Eastern European who has witnessed the rapid spread of capitalism at close hand, the irony with which it has left us with one vast “West.”

Following the fall of the Berlin Wall, Krasznahorkai embarked on protracted travels throughout Asia. He has engaged in a profound intellectual involvement with the cultures of the East, particularly Japan and China. His book Destruction and Sorrow beneath the Heavens, forthcoming from Seagull Books, documents the disappearance of the last traces of ancient Chinese culture on the very brink of the economic boom. Anglophone readers of Krasznahorkai will be familiar with the trope of the individual from a former dictatorship who is too scarred to bear the sight of beauty; the systematic humiliation and deprivation he has been subjected to have brought about a coarseness and vulgarity, a loss of dignity and self-respect that renders the search for truth meaningless and even dangerous. Here, however, it is more a matter of indifference towards a four-thousand-year-old history that is increasingly being forgotten.

In his essay “About Gods Bereft of their World,” Sándor Radnóti asks if Seiobo There Below is a “new version of art as religion” or “a kind of exclusive personal and artistic travelogue” describing a collection of “specimens of the total (high) culture which functions as the foundation stone of a syncretic religion, whose inspired prophet is the author himself.” Of the recurrent figures in Krasznahorkai’s writing, i.e. the Prophet, the Archivist, the Observer, or the Seeker, it is the false prophet whom Radnóti interrogates—and his skepticism reveals the degree to which he takes the author at his word. This and other essays comprise the wealth of critical analysis and material hitherto unpublished in English translation contained in Issue Two of the arts magazine Music & Literature. Devoted to Krasznahorkai, director Béla Tarr, and German visual artist Max Neumann, the issue is an essential and comprehensive resource that brings together numerous in-depth investigations into Krasznahorkai’s overall literary project that illuminate his development throughout the past thirty years. In the interview quoted above, Ottilie Mulzet, who has tackled the problem of transferring a literary form encased in a “fragile, faraway language” such as Hungarian (not to mention a Central European culture largely unknown beyond its borders), of capturing the “multidirectional quality” of his syntax and translating it into a world language such as English, offers intimate insight into Krasznahorkai’s language and oeuvre. Also among the essays in this issue is an astonishing text by David Auerbach titled “The Pythagorean Comma and the Howl of the Wolf” that examines the “Werckmeister Harmonies,” the central section of The Melancholy of Resistance (and of the film it gave rise to), specifically the keyboard tuning that serves as the essential metaphor for the entire book. At stake is a minimal departure from the absolute purity of musical pitch—and whether “what is clearly a spiritual experience . . . has any real connection to the cosmos and the world.”* * * *

It is generally considered plausible today that human aesthetic activity can be traced back to the visionary. Scientific evidence suggests that human consciousness underwent a profound change around 40,000 years ago, when our Paleolithic ancestors first began painting in caves. The images they produced, among them spirals and geometric shapes, bear resemblance to entoptic phenomena, or the images the human mind perceives under the influence of hallucinogenic substances. This suggests an early relationship between the making of objects/images defined as “art” and altered states of consciousness—whether attained through psychoactive substances or through prayer, meditation, or ritualized dance—that has existed since human beings first began engaging in what we call aesthetic activity. The birth of art, then, may have derived from a need to portray not the animals of the hunt or other everyday occurrences, but the luminous and powerful images perceived within the human mind; in all likelihood, it is inseparable from the birth of mystical experience.

But this is not merely an obscure phenomenon of the distant past. As mathematicians and physicists succeed in locating human consciousness in the interface between quantum physics and molecular biology, science is at the vanguard of a discourse that has traditionally been art’s domain. In analyzing the fundamental historical differences between Eastern and Western conceptions of the sacred, Krasznahorkai reminds us that much of what we call art today has left the realm of communal experience and has ceased to be the vehicle or language humans use to communicate essential, ineluctable truths. As he explores under what conditions the sacred might still be perceived in art, he also, by implication, examines the possibility of meaningful aesthetic activity in contemporary times.

The project to reclaim art’s essential role in formulating the basic questions framing our existence is more modern than ever, perhaps even radically so. Seiobo There Below does not propose a new kind of pseudo-religion or the apotheosis of the artist as divine genius. Nor does it announce the death of art. There is too much crystalline joy in the writing, too much devotion in the excursions on artistic method and technique, too much humble exactitude in the portrayals of religious ceremonies. In “The Preservation of a Buddha,” as the elaborate ceremony to restore the divine light to the eyes of the Amida Buddha is nearing its final moments, “there is something now in the Hall which is difficult to put into words, but everyone present can sense it, a sweet weight in the soul, a sublime devotion in the air, as if someone were here, and it is most evident on the faces of the non-believers, the merely curious, the tourists, in a word the faces of those who are indifferent, it can be seen that they are genuinely surprised, because it can be felt that something is happening, or has happened, or is going to happen, the expectation is nearly tangible ( . . . ).” The question as to whether or not Krasznahorkai believes in or shares the metaphysical and religious experiences he describes is largely irrelevant in light of the fact that, for the attentive reader, the accumulative force of his words bring about the selfsame effect he takes such pains to describe. At its core, Krasznahorkai’s writing is always, deeply, ambiguous. -

László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below has been hailed as a book about the sacred. For the fictional artists described in the collection, transcendence comes through the act of creation. In one story, a Japanese theatre master takes the stage and feels the goddess Seiobo coursing through him. In another, a maskmaker’s chisel moves nearly of its own accord, fashioning a series of wooden faces that are almost alive. But Krasznahorkai also turns his attention to another genre of protagonists: average people who encounter the sacred, completely unequipped to contend with its impact. While the book’s artists find transcendence, other protagonists experience utter bewilderment — and their crisis is the focal point of the 17 stories in Seiobo There Below.

Seiobo translator Ottilie Mulzet notes in her interview with Krasznahorkai that he addresses what has effectively become taboo: “The question of ‘sacred’ in a world which has no need for it anymore.” The Hungarian author’s works are known for their promise of higher meaning and their tendency to approach, but never quite reach, resolution. Krasznahorkai’s previous titles in English (War & War, The Melancholy of Resistance, and Satantango) earned critical recognition from Susan Sontag and James Wood for their strange, apocalyptic impression. Rife with peculiar characters and sealed into sophisticated structures (Satantango adopts the form of the tango dance, while Seiobo There Below, though billed as a novel, presents distinct stories numbered by the Fibonacci sequence), Krasznahorkai’s fiction makes contact with the otherworldly.

But the stakes are higher in Seiobo There Below. For one, the global nature of the collection is a marked departure from Krasznahorkai’s former English-language releases. The novels that earned him his reputation in America were texts with deeply Hungarian roots. The Melancholy of Resistance and Satantango were both set in crumbling Hungarian villages; War & War featured a Hungarian protagonist newly moved to New York City. Seiobo, in contrast, spans locations from Kyoto to Persia and Perugia. Its narrative voices are equally diverse; we hear from a nascent murderer, a fanatic lecturer on Baroque music, a Parisian museum keeper in love with the Venus de Milo. Moving beyond localized meaning, the stories challenge us to examine the psychology of our moment, a time in which our inability to understand the sacred paralyzes us in its presence.

This bewilderment manifests itself in several narratives of Western European travelers knocked spiritually unconscious by the impact of sacred art. In “Christo Morto,” a traveler is drawn into Venice’s Scuola de la Roca to revisit a painting of Christ he had seen 11 years prior. He witnesses the image of Christ opening his eyes and is frozen by disbelief:

BUT HE IS OPENING HIS EYES, he registered within himself; then again he tried to muster the courage to fix his gaze onto the two eyes of Christ, BUT HOW DARK are these eyes, it was spine-chilling, as although NOW THEY REALLY WERE ALMOST COMPLETELY OPEN, you could hardly see the pupils, and nothing in the white of the eyes, it was completely clouded, a dark obscurity lay in these eyes…and here is Christ REALLY AND TRULYThe capitalization, the quick cadence of thoughts, the terror in beholding the eyes: this man’s franticness is palpable in the text. Bewildered, he sits and stares, then decides to turn away from the painting and leave the Scuola in hopes of dismissing such terrible thoughts. But the last line of the story — “For him there would never be any exit from this building, not ever” — reveals the inescapability of his new, disoriented state.

The next story, “Acropolis,” reiterates this feeling of bewilderment. The protagonist of the tale journeys to Athens fulfill his lifelong wish of visiting the ancient site. He arrives at the site only to find the limestone so bright that his eyes ache and tear. Unable to bear its radiance, he stops his ascent in pain and bitterness, asking himself why no travel guide, no art historical account, had warned him about the blinding light. His bewilderment grows from the expectation that he could have foreseen, let alone overcome, this trial. How could he have known the luminosity of this place?

Not all characters in Seiobo There Below reveal such blatant bewilderment. Several try to understand the sacred by cycling through methods tried and true: scholarly intercourse, scientific inquiry, mathematical analysis. Ironically, the characters who pursue answers down these clear pathways are among the most disconnected. At intervals throughout “Christo Morto,” for instance, we learn about an art historian who had tried to restore the Scuola’s painting of Christ. She brings the painting to a chemical restoration workshop in hopes of discovering the original artist, a mystery over which the board of San Rocco holds its breath. When the chemical restorer X-rays the image and examines the gesso, he finds an underwhelming signature. The painting is left half-forgotten in a small corner display. The art historian is so focused on the work’s scholarly evaluation that she misses the essence of the painting.

This intellectually fueled oblivion percolates through the stories. When a European scholar tries to study the rebuilding of Japan’s Ise Shrine, she misunderstands the tradition to such a point that she obscures the rite’s actual meaning. When a group of travelers camps out in the Carpathians to foster creativity, they grow so preoccupied with their routine that the true artist among them — an elusive man who carves an enormous earthen sculpture — becomes a spectacle.

As one bewilderment follows another, the repetitions themselves start to hold higher meaning. The arrangement of narratives into the Fibonacci sequence is no coincidence. Like the mathematical series, the stories in Seiobo There Below evoke a spiral, both recursive and unexplainable. Plots reoccur, protagonists resemble each other, and narrators repeat phrases as they circle around the topic at hand, always one inch short of final revelation. As one narrator remarks, “Not to know something is a complicated process, the story of which takes place beneath the shadow of the truth.” This is the philosophy of Seiobo There Below. László Kraznahorkai has given us a work that shimmers under a prism of hidden meanings. Our task is to connect the dots, experience the mystery of the text, and embrace moments of bewilderment with patience, openness, and preparation for a deeply meaningful encounter. - Stephanie Newman

Hell is oneself. Or, if you like, Hell is other people. Either way, Hell’s Modernist vanguard—let’s say Beckett, Sartre, and Eliot—moiled in darkness long enough to recover the bad news and bring it to daylight. Their message? Hell will last as long as we do. Even as their more lighthearted disciples wrung the hereafter, drop by drop, of its holy water, these true believers never sinned against the Dantean orthodoxy that preaches Hell’s totalizing hopelessness. It is worth noting, after all, the titles of their best dramas—Endgame, No Exit, and The Cocktail Party—are euphemisms for Hell.

The Modernists found their most potent expression of Hell in drama, or more specifically, the scene. For Hell’s vanguard, the scene as a form preserves the weight of its etymological origins, implying a stage as much as a unit of dramatic time. It was left to Beckett and Sartre to defamiliarize the scene by literalizing it; only then could it become a symbol for centurial ills. Once its exits were blocked—its spatial and temporal limits made literal—the scene transmuted into paradox: a closed loop, a machine of surveillance and its attendant nausea, an orchestra of trapped bodies that played out the fears of a crowded, exhausted world. With Beckett’s Endgame, the scene reached its endgame. Once a chamber, then a cell, the scene became Hell:

HAMM:

Stop!

(Clov stops chair close to back wall. Hamm lays his hand against wall.)

Old wall!

(Pause.)

Beyond is the…other hell.

✖

No contemporary writer has tarried in literary Hell more faithfully—or more convincingly—than the Hungarian novelist László Krasznahorkai. In the almost thirty years since his first novel, the infernally-titled Satantango, Mr. Krasznahorkai’s vision of society as an inescapable Hell of its own design has never lapsed. It is an ever-expanding world of deceit and human folly, one spun by interminable sentences that spread quaquaversally, like wild flames, scorching hope wherever it writhes. True to Beckett and Sartre before him, Mr. Krasznahorkai’s Hell always manifests itself as a scene or closed circle. Though these closed circles are of human design, they are populated by demons who are paradoxically all too human. These demons, themselves deeply acquainted with Hell—the closed circle that never opens—choreograph set pieces of swindle and deceit that lead innocents and the willfully gullible to inexorable doom. In this respect, Mr. Krasznahorkai’s work sharply recalls Pushkin’s “Demons,” a poem later used as an epigraph by Dostoevsky in his novel of the same name:

Strike me dead, the track has vanished,

Well, what now? We’ve lost the way,

Demons have bewitched our horses,

Led us in the wilds astray.

In Satantango—which implies, yes, a dance with the devil—the closed circle is a failed farming collective lost in the mist of post-Communist Hungary. The novel’s foremost demon is the false prophet Irimiás, who gives pithy expression to Mr. Krasznahorkai’s vision in the form of a hilarious, viciously-circular address:

I see this tragedy as a direct result of your condition here, and in the circumstances

I simply can’t desert you.

With Mr. Krasznahorkai’s second novel, The Melancholy of Resistance, the closed circle snakes outward, assimilating the doomed souls of a Hungarian village. The village is roiled by the arrival of a circus that brings with it the cadaver of an enormous whale. Counterposed to the whale is the circus’ homuncular ringleader, named The Prince, another false prophet. The Prince orchestrates a meaningless act of mob violence, one that ruins the “half-wit” delivery boy Valuska, a Shakespearean fool who harbors ecstatic faith in the universe.

As its title would suggest, 1999’s War and War confirms that there is no escape from the closed-circuitry of greed and militarism that defines the globe at the turn of the century. Mr. Krasznahorkai aptly sets his novel in New York City, thought by the angelic Korin to be the center of the world. The city instead reveals itself to be a mega-Babel on the verge of ruin, on the precipice of being “brought low,” as Korin prophecies in the final section. In the figure of Korin, the novel almost imperceptibly joins idiot with prophet, until what emerges is a Cassandra, a confounding voice whose ecstatic revelations about crumbling towers and the coming war are perilously ignored. By the time his searing prophecies become intelligible, the loop is already closed:

Korin was slowing again—but actually that was not the right word, hopeless was

somehow wrong, there was no way out of this deadly loop, since it was ready and

fully functioning in its own way, and calling it hopeless was not going to foul up

the works, quite the contrary, in fact, it would simply oil them, bring a constant

shine to them, help them to function.

✖

With Seiobo There Below—the author’s latest novel, now published by New Directions and expertly translated by Ottilie Mulzet—the closed circle, the terrible web of human folly, has expanded to include several historical periods strewn with innumerable depictions of ascetics, murderers, gods, and artworks of terrorizing beauty. Only it is at first difficult to give name to this circle because the title and the first chapter and even the formal structure of the book amount to a demonic ruse, one that tricks the reader into believing he will bathe in the springs of Eastern transcendence. The title itself hints that the goddess Seiobo will descend unto the earth below, that she will count the rhythm of mortal life against the untroubled silence of the eternal. Mr. Krasznahorkai’s ruse is abetted by anecdote: we know that the novelist spent the last decade traveling throughout Asia, especially Japan and China, where, in search of the sacred, he observed Noh masters and ancient statues of the Amida Buddha. It would appear from the preliminary evidence that Mr. Krasznahorkai has shed the disciplined madness of his storyteller—the one who brought us so much chaos—for the impartial gaze of the goddess eye.The narrator of Seiobo begins by contemplating the cadences of nature by way of a serene lilt, one that matches the flow of the Kamo River and observes the Ooshirosagi, a white bird poised in an S-curve that no sculptor could render:

…and even the entirety of words that want to describe it do not appear, not even

the separate words; yet still the bird must lean upon one single moment all at once,

and in doing so, must obstruct all movement: all alone, within its own self, in the

frenzy of events, in the exact center of an absolute, swarming, teeming world, it

must remain there in this cast-out moment, so that this moment as it were closes

down upon it, and then the moment is closed, so that the bird may bring its snow-

white body to a dead halt in the exact center of this furious movement, so that it

may impress its own motionlessness against the dreadful forces breaking over it

from all directions…

Did the fever break in Mr. Krasznahorkai’s prose? Gone is the viper’s nest of idiots, fools, and prophets; instead there is only the bird and the river and the alien narrator. Until, from nowhere at all:

…it would be better for you to go away this very evening when twilight begins to fall,

it would be better for you to retreat with the others, if night begins to descend, and

you should not come back if tomorrow or after tomorrow, dawn breaks, because for

you it will be much better for there to be no tomorrow and no day after tomorrow;

so hide away now in the grass, sink down, fall onto your side, let your eyes slowly close,

and die, for there is no point in the sublimity that you bear, die at midnight in the

grass, sink down and fall, and let it be like that—breathe your last.

Fall onto your side and die. There is no tomorrow and no day after tomorrow. Actually it is worse than this, as the reader of Seiobo will eventually learn over the course of seventeen scenes. It is worse because of Mr. Krasznahorkai’s ruse, which is actually a revelation of something we have forgotten. And the ruse is demonic, precisely due to what is revealed. The novelist now writes about transcendent gods because he wants to remind us that the only escape from the closed circle of human misery is the fleeting contemplation of the aesthetic sublime, one that is tied inextricably, in every epoch, to the divine. This contemplation is fleeting, he tells us, because the gods are fleeing from the Below—where we reside—which is not merely the earth but the inescapable Hell of human relations.

✖

The structural burden shouldered by Seiobo There Below is enormous; to stay true to the author’s vision and ambition, the novel must erect an inescapable Hell that spans ages and contains both apogee and perigee of human creation. Mr. Krasznahorkai’s solution to this problem amounts to a startling formal development, at once a renovation of Dante’s infernal edifice and a novelization of the closed loop developed by Beckett and Sartre. In short, Seiobo proceeds by way of seventeen scenes, each of which spins a narrative on the theme of failed transcendence. It is almost as if Mr. Krasznahorkai has condensed the architecture of his prior novels into unbearably taut episodes. And although these episodes or scenes are temporally disjointed—one may linger in fifth century Persia, the next in contemporary Japan—they form an arpeggio; only the reader cannot, until it’s too late, determine whether its notes are rising or falling.Of course, scenes demand players, and there is no shortage of figurative and literal actors in Seiobo. The most memorable of these is Master Inoue Kazuyuki, whose incredible discipline as a Noh master affords the novel a rare glimpse of human triumph. As his scene begins, it is impossible to tell the difference between Kazuyuki and Seiobo, the goddess whom he incarnates on the stage; Mr. Krasznahorkai’s prose weaves between them, penetrating the human and divine in equal measure, until it settles in the Hell below, where we learn how Master Kazuyuki once tried to persuade his family to join him in a mass suicide.

Scenes, too, even as closed loops, require spectators, and, most crucially, their gazes. The word gaze abounds in Seiobo. Early, and often, the gaze is an object of discipline; it must be trained in order to sustain contemplation of the beautiful, and only in this way does the novel proffer the possibility of transcendence. Eyes in the novel overpower with their significance, especially when they peer from art works imbued with the aura of ritual, as in the case of the Amida Buddha:

…but they cannot bear to look away from Amida, for most of the believers remember

very well how the statue looked across the decades, a dark shadow on the altar, with

almost no contour, almost no light, yet now it is truly resplendent, resplendent in the

wondrous face the wondrous eyes, but this pair of eyes, if even touching lightly upon

them, does not see them but looks onto a further place, onto a distance that no one here

is able to conceive…

On the other hand, the undisciplined human gaze, which it turns out, belongs to every one of us, resolves itself in the pure Hell of the other. Of course, the idea that “Hell is other people” is premised on the gaze that was so crucial to Sartre’s Being and Nothingness and No Exit, where the look or gaze of another is the fount of existential anxiety and dread. Allusive variations on the phrase “no exit” recur throughout Seiobo, most powerfully in the chapter titled “Christo Morto,” which takes place in Venice and works as a comedic (if disturbing) revision of Sartre’s own essay on the same. In the opening section of “Christo Morto,” the protagonist thinks that a man in a pink shirt who “gazes” at him is also trying to murder him. When he turns to look back at the man, while crossing a bridge, the “chilly sensation in his body” escalates from “anxiety” to “sharp fear.” When the protagonist finally realizes that he is not being chased at all, he sits at a café, orders a cup of coffee, and reads a newspaper headline, one that quotes Pope Benedict:

HELL REALLY EXISTS

The man attempts to shrug off the headline (“there’s no heaven, no purgatory, that’s fine, to hell with the whole thing”), but he is plagued by the notion that he is somehow, mysteriously, “flirting with danger.” Later he visits the San Rocco, where, like Sartre, he seeks the paintings of Tintoretto. Instead he becomes literally captivated by an anonymous painting of a Christo morto or Dead Christ—in a moment that catches Mr. Krasznahorkai’s sly wink to Sartre in a frieze. As the man attempts to flee the terror of the Dead Christ, to exit the San Rocco, he has no idea that for him “there would never be any exit from this building, not ever.”✖

While contemplating a novel with its own Cristo morto—Dostoevsky’s The Idiot—Walter Benjamin once noted that “the concept of eternity negates infinity.” It is now obvious that Seiobo There Below is the purest expression of this principle in contemporary literature, especially if we take “eternity” to mean “unending Hell.” To illustrate the way Hell eats infinity, Mr. Krasznahorkai embellishes his novel with a cruel joke. Its sections are arranged according to the Fibonacci sequence, a series where successive integers are always the sum of the prior two. The Fibonacci sequence is often rendered visually as a spiral, toward infinity, and this optimistic picture is routinely paired with the observation that the ratio between two Fibonacci numbers is very near what we have come to know as the Golden Ratio, that mathematical foundation of uncountable human masterpieces in architecture, painting, music, and more. Of course, the novel reminds us again and again that such aspirations toward infinite expression are bound to be lost in the eternal sway of human lunacy. It is just as probable, anyway, that the infinite spiral implied by the Fibonacci sequence points downward, to the Below.The penultimate chapter of Seiobo, “Ze’ami is Leaving,” ends with a corpse. The final chapter, “Screaming Beneath the Earth,” as the title suggests, is nothing but pure Hell, one that plays out the Mephistophelian joke begun with the Fibonacci sequence:

…they are hidden deep below the earth in the darkness, and with their mouths

open wide they scream, the graves they were meant to serve collapsed onto them

long ago; and collapsing in layers, buried them completely, so that they became

walled into the earth, among the stolons, the ciliates, the rotifers, the tardigrades,

the mites, the worms, the snails, the isopods…and before their cataract-clouded

bulging eyes could stare, for the earth is so thick and so heavy, from all directions

there is only that, everywhere earth and earth, and all around them is that impen-

etrable, impervious, weighty darkness that lasts truly for all time to come…