![Image result for Donald Westlake, Memory,]() Donald Westlake, Memory, Hard Case Crime, 2011.www.donaldwestlake.com/blog/

Donald Westlake, Memory, Hard Case Crime, 2011.www.donaldwestlake.com/blog/THE CRIME WAS OVER IN A MINUTE –

THE CONSQUENCES LASTED A LIFETIME

Hospitalized after a liaison with another man’s wife ends in violence, Paul Cole has just one goal: to rebuild his shattered life. But with his memory damaged, the police hounding him, and no way even to get home, Paul’s facing steep odds – and a bleak fate if he fails…

This final, never-before-published novel by three-time Edgar Award winner Donald E. Westlake is a noir masterpiece, a dark and painful portrait of a man’s struggle against merciless forces that threaten to strip him of his very identity.

While on tour, actor Paul Cole is caught in flagrante delicto with another man’s wife. The other man beats Paul into unconsciousness, and when he awakes in a hospital bed, he can’t remember where he is or what happened to him. Can a man whose memory is irretrievably shattered hope to rebuild his life? This previously unpublished novel was written early in Westlake’s career, and it feels that way: it’s written in the crisp, unadorned style of The Mercenaries, Killing Time, and 361, all of which were published in the early 1960s. Unlike most of Westlake’s books, Memory isn’t really a crime novel; it’s a psychological drama, the story of a man trying to find his way back to his own life. Westlake’s fans will note the author’s typically careful use of description and dialogue, but they may also be a bit stymied by his central character: Cole thinks of himself at one point as a steel marble in a pinball game... always in motion, and that seems just right for a man bouncing from moment to moment, reacting to events but never taking control of them. Compared to a typical Westlake protagonist, Paul Cole feels weak and ineffectual—likable but a bit pathetic. But this is no typical Westlake novel; in fact, in many ways it’s one of his most interesting books, simply because it’s so very different. For his fans, absolutely a must-read. -

David Pitt

The career of late MWA Grand Master Westlake (1933–2009) spans 50 years with the appearance of this elegant, melancholy novel, written in the 1960s and never before published. Actor Paul Cole is on tour when he sleeps with the wrong married woman, and her husband puts him in the hospital, from which he emerges with short- and long-term memory problems. As he makes his way from the Midwest to his home in New York City, Paul struggles to remember his past and build a future while existing in limbo: unable to keep appointments with doctors or the unemployment office, meeting countless people too caught up in their own agendas or bureaucracies to help him. Lovely language and the overall discourse on the consequences of thoughtlessness make this a significant final work from a master. -

Publishers Weekly

I can't believe there are still some readers out there who have never had the pleasure of reading a Donald Westlake novel. A man of multiple pseudonyms- at least seventeen by my count- Westlake (1933-2008) had a writing career that lasted some fifty years. It's hard to say exactly how many novels he wrote. Most likely over a hundred, while some twenty-five of his novels have been adapted for the screen. Then there are his screenplays, not least of which is his adaptation of Jim Thompson's The Grifters, directed by Stephen Frears in 1990 (not to mention his screenplay for Dick Spottswood's 2005 adaptation of Patricia Highsmith's Ripley Under Ground).

Most hardcore crime readers would no doubt favour Westlake's novels written under the name Richard Stark. For no other reason than those books mark the essence of modern stripped-down, fast-moving tough-guy crime fiction in the tradition of Paul Cain and Hammett. I suppose if Westlake is known for one book it would probably be The Hunter, if only because that's the novel on which John Boorman based his 1967 film Point Blank. As excellent as Boorman's film is, it differs considerably from the novel.

Then there are all those Westlake comic crime novels featuring John Archibald Dortmunder ("My own worst fears when I get up in the morning," said Westlake regarding his creation. "He's everything that can go wrong."). An unlucky criminal genius, Dortmunder first appeared in the 1970 Hot Rock, which began as a Richard Stark novel, but Westlake realised the novel, concerning someone who commits the same crime over and over again, was moving away from the hardboiled style of the Parker novels. With his eccentric concept of criminality, Dortmunder would go on to feature in more than a dozen novels.

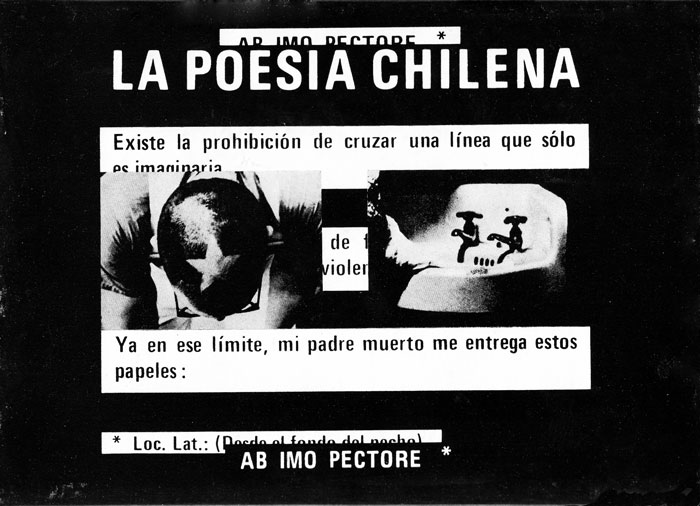

![]()

Other than the Stark novels, my personal favourite Westlake books are what I call his "social" novels, like The Ax, The Hook and his final novel Memory, published posthumously by Hard Case Crime in 2010. Not that other Westlake novels lack a social dimension; in fact, they are all subtly political regarding the way they expose society's fissures and failures. For instance, the Stark novels, in which Parker, ever the individualist, battles against organized crime, in other words corporate capitalism. But, for me, Westlake's "social" novels are more explicit in their critique and commentary, whether concerning, as in The Ax, someone who finds himself unemployed, and so, to maintain his life style, sets out to murder anyone competing for the job he's after. Or, as in The Hook, about a successful novelist who has come down with a case of writer's block, so, to once again keep up his life style and help pay off his divorce, hires a hack writer, to write his next novel, which turns out to be a success. Which means even though the two writers will split the money, the hack writer, as part of the deal, and in what could be viewed as an updating of Highsmith's Strangers On a Train, has to the other man's divorce-seeking wife.

Likewise, Westlake's final and posthumously published (Hard Case Crime) novel, Memory, which I only came across recently. It's a novel full of surprises in which Westlake moves from the social to the margins of philosophical speculation, as he examines the relationship between memory and identity. Writer

Luc Sante has called this novel "hardboiled Kafka," and he's not far off the mark. Not without humour and never stretching credulity beyond breaking point, Memory recalls one of Westlake's earliest (technically his second novel, if one discounts earlier soft-core porn efforts), Killy, about a couple union organizers called into a company town, only to be implicated in murder, although Memory is a more mature and well-rounded novel. And, as usual, Westlake rarely wastes a word.

It's a novel centered on Paul Cole, a New York actor in a traveling theater group working in a middle-American small town. There he has a one-night stand with a woman whose husband discovers them together and hits Paul on the head with a chair- "What a cliché," acknowledges Paul- rendering him unconscious. He awakes in a hospital with amnesia. The doctors assure that his condition is temporary. However, the authorities make it clear that someone with such loose morals is not welcome in their town, so accompany him to the bus station where Paul gets a ticket as far as his money will take him. Not to New York but to another small town where he finds work in a tannery. He more or less settles into life there, has friends, including a girlfriend, but, though he doesn't realize why, he knows he must return to New York. It's only when he finally arrives there that his real troubles begin.

I can't think of many novels that examine so closely the relationship between identity and memory, as well as its various implications. After all, if one's memory is wiped out, where does that leave the entire nature vs nurture debate? And what remains of the person? What is the person other than his memories? And if one's circumstances dictate, to some extent, one's personality, can one, should amnesia strike (that Paul has partial amnesia only complicates matters), simply start over? Longer than the usual Westlake/Stark novel, Memory might also be Westlake's most literary effort. "Literary" in the sense of mainstream fiction. Which isn't to say other Westlake novels are not literary; in fact, they are deceptively so, even if they are left to define their own particular literariness. Moreover, Memory might also be Westlake's most personal novel, as it delves into a subject befitting someone moving into the last years of his life.

I admit that I'm no expert when it comes to Westlake's fiction, but I can say that I've appreciated everything I've ever read by him. And, if nothing else, Memory seems to be a fitting end to a long and perhaps under-appreciated career. If you haven't read Westlake, Memory is as good a place as any to start. And if you have read him, you won't want to miss this novel... -

Woody Hauthttps://woodyhaut.blogspot.hr/2018/02/i-remember-therefore-i-am-memory-by.htmlWhile on tour with a stage-company, actor Paul Edwin Cole gets caught in bed with a woman by her husband. The husband beats up Paul badly enough to knock him out for fifty-eight hours and send him to the hospital; when he wakes up, Paul is a changed man. He remembers some things, like his name, but not much. His short-term memory is poor: he forgets things like the nurse's name. Not unexpected side-effects from a massive concussion -- except that in Paul's case they last. And last and last.

It's not real amnesia, "it's just that everything sort of fades" is how Paul describes it.

I remember just bits and pieces of things. My memory is like a sieve, everything runs through it. In a few days, I'll probably forget talking to you. The theater-group ditched him and moved on, and the police are eager to get him out of town as son as possible, too, so after about two weeks in hospital they escort him to the bus station and send him on his way. His way is in direction New York -- his home address still rings some sort of bell, and he knows the key to figuring out who exactly he is lies back there -- but he doesn't have enough cash to get all the way there. So he goes as far as he can afford - a place called Jeffords --, and takes it from there.

His limited memory makes things problematic. He has to write himself notes to remind himself of things. The lack of money is even more problematic, but he gets a job (in a tannery) and tries to save up -- which takes a while, because of his expenses, like room and board. The life isn't bad: he likes the family where he has a room, he likes the work. And he even gets himself a girl he likes, Edna.

But his goal is New York -- he knows he has to go there, and eventually, when he has enough for the bus fare, he leaves Jeffords and heads back home. Except that it isn't really home any longer. A great deal is vaguely familiar, and he recognizes some of the people he encounters -- friends, his agent -- but he's not his old self any longer. And he's certainly no actor: he can't memorize lines, and he can't play the part -- any part -- either: the cocky, sure-of-himself man is now only a shell of himself. Try as he might, he can't recapture that old self.

It takes him a while to work things out, but he realizes he's stuck in this condition. He can barely relate to the people he used to hang out with -- or rather, they have trouble relating to him -- and he has difficulty figuring out what he should do with himself. One thing he notices, however, is that some memories are sticking with him. There's a disturbing one of some metal object that plagues him, though he can't figure out exactly where to place that memory. But there's also the memory of Edna, and the inkling that maybe that life he abandoned was the better one for him.

Westlake fashions a surprisingly compelling novel out of this fairly basic premise and simple story, managing an impressive balancing act with this material that could so easily get monotonous (or irritating) -- especially considering how long the novel is. Westlake injects some moments of tension -- encounters with the police, flashes of aggression, Paul's money trouble -- but for the most part this is a subdued novel (just as Paul is now very subdued) of a man trying to find his way, forced to tackle all those big philosophical questions -- right down to 'Who am I ?' -- in a much more direct way than most.

Memory is a

noir novel, centered very much on its now-loner protagonist. Paul thinks he has a mystery to investigate -- to figure out who he is -- and he goes through the detective-motions. But the pieces, even as they add up, don't help him. What he really has to do is figure out who he wants to be.

Lost soul Paul sees he can't reclaim his life in New York, and he eventually makes his decision, whether to stay or go. But even in its ending,

Memory remains true to the genre, existentialist

noir through and through.

It's bleak stuff -- though always with a bit of hope shining through -- and very good. Westlake shows he had the writing chops; it's a shame (and shameful) that his agent had him put it back in his drawer because it was supposedly 'too literary'. Recommended.

- M.A.Orthoferhttp://www.complete-review.com/reviews/westlake/memory.htmThe Drowning MachineEd Gorman BlogElle(French)Entertainment Weekly D Gary GradyVince KeenanMostlyFiction Book Reviews Old BonesPornokitschSomebody Dies Spinetingler MagazineThis Writing LifeWeekly StandardLIKE MOST PEOPLE who spend too much time with books when they are young, I eventually developed the urge to write myself but found it difficult to write anything I enjoyed reading. Largely this was because I either tried too hard or was emulating so many different writers that I couldn’t establish any control over basic fictional techniques. I was too busy hunting through my Thesaurus for complicated-sounding words and manufacturing pretentious, apocalyptic stories about worlds and landscapes I didn’t know anything about.

Then, in my early teens, I attended a “speculative fiction” writer’s conference in Seattle. One of the guest writers was Harlan Ellison, known then (and now) as a funny, aggressive, short, challenging, charismatic, and unconventional writer of manifestly angry short stories, screenplays, and essays. (It may only be my imagination, but I seem to recall seeing him, on more than one occasion, marching around the lobby of our busy dormitory wearing only a terrycloth bath towel strapped around his waist while smoking a big ornate meerschaum pipe.) And while there are good reasons for remembering his larger-than-life personality, to this day I recall him simply as a lover of books. He was constantly throwing around the names of writers I didn’t know, and I was constantly scribbling those names into one of the notebooks I was constantly losing. Then, near the end of that first uncomfortable week, when it was growing increasingly apparent to everyone (especially me) that my fiction was pretty bad, Harlan Ellison gave me a piece of piece of good advice that I have never forgotten: “Throw out that fucking copy of

Finnegans Wake you’re always carrying around and go read Donald E. Westlake. He’ll teach you everything you need to know about writing fiction. Oh, and pick up some acne medication while you’re at it. Your face’s a mess.”

The day after Harlan Ellison issued his marching orders, my friend Gus Hasford and I took our daily walk into Seattle and picked up several Westlake paperbacks that were pretty widely available. We found them in the battered, rain-stained bargain boxes outside thrift stores, in the squeakily revolving racks at Safeway and 7-Eleven, and even displayed in the front windows of bookstores among the latest crime and mystery releases. As I recall now, they were distinguished by their almost uniformly terrible covers: lots of blank white spaces populated by office equipment, hippy-like women in short skirts and beads, and men in slacks, shirts, and ties (no jackets). And while there might be a gun located here or there among the mannequins, the images suggested middle-aged attractive people plotting murder while writing memos and typing correspondence.

Sometimes there was just a simple, iconic bank vault on the cover, or a bunch of

Mad Magazine–style gangsters chasing each other around with machine guns. And the titles (at first glance, anyway) were likewise flat and anonymous-sounding:

The Hot Rock (1970),

Bank Shot (1972), and

Help I Am Being Held Prisoner (1974) — the first three Westlake titles I took home with me that afternoon. My first impression was that they looked extremely boring and conventional, something my parents might like. I had no idea what this Harlan guy was talking about. They didn’t look like “serious writing” at all.

And so I picked one up that evening in the top level of my college bunkbed and didn’t put it down again until I finished well after midnight. And by sometime early the next afternoon, I had read them all.

Those first Westlake books zipped by so quickly that I wasn’t even aware I was reading them until they were over. And unlike all the “serious” and “noteworthy” books I usually tried to read, they never had me anxiously checking how many pages there were left until the next chapter, or looking up words in the dictionary, or skimming back over the previous pages to find something I had missed. Every image leapt off the page; every scene quickly set me in a location so vivid and immediate that it felt like I wasn’t entering some fictional space but simply remembering an actual location where I had already been. And every line of dialogue opened up the voice and personality of the character who spoke it. Take, for example, this opening page from the second Westlake novel I ever read,

Bank Shot:

“Yes,” Dortmunder said. “You can reserve all this, for yourself and your family, for simply a ten-dollar deposit.”

“My,” said the lady. She was a pretty woman in her mid-thirties, small and compact, and from the looks of this living room she kept a tight ship. The room was cool and comfortable and neat, packaged with no individuality but a great passion for cleanliness, like a new mobile home. The draperies flanking the picture window were so straight, each fold so perfectly rounded and smooth, that they didn’t look like cloth at all but a clever plastic forgery. The picture they framed showed a neat treeless lawn that drained away from the house, the neat curving blacktop suburban street in spring sunshine, and a ranch-style house across the way identical in every exterior detail to this one. I bet their drapes aren’t this neat, Dortmunder thought.

“Yes,” he said, and gestured at the promo leaflets now scattered all over the coffee table and the near-by floor. “You get the encyclopedia and the bookcase and the Junior Wonder Science Library and its bookcase, and the globe, and the five-year free use of research facilities at our gigantic modern research facility at Butte, Montana, and —”

“We wouldn’t have to go to Butte, Montana, would we?” She was one of those neat, snug women who can still look pretty with their brows furrowed.

Within four brief paragraphs, two characters have come to life: a weary con man with some encyclopedias (the literary equivalent of swampland in Florida) he wants to sell and an obsessively “neat,” infinitely repeatable middle-class woman who’s so busy worrying about what the con man’s right hand is showing her (“We don’t have to go to Butte, Montana, do we?”) that she never realizes the left hand is offering her piles of glamorous stuff she will never see. Each image is vivid and exact — the stiff, plastic-looking curtains; the promo leaflets scattered over the table; and the blacktop curving off over the edge of the meaningless suburban planet — so that the reader is propelled into a landscape filled with voices, urgency, and confrontation. Then, just as the con man (his name is Dortmunder, and he eventually occupied more than a dozen of Westlake’s caper-comedies) awaits delivery of another 10-dollar bill to his wallet, he hears this supposed born-sucker in the other room calling the cops. Maybe, he thinks suddenly, she isn’t as dumb as she looks — and he turns out to be right.

That’s because nothing goes quite where you expect it to go in a Westlake novel, and these perfect little comic dislocations satisfyingly occur over and over again, always perfectly composed, always surprising, and always delivering what

had to happen. Sentence after sentence. Scene after scene. And book after book. Until, of course, you start the next one.

Westlake didn’t wear “big ideas” on his sleeve, but that doesn’t mean he didn’t have them; and even at their most entertaining, his novels deliver an unforgiving picture of a postwar United States in which the overriding philosophy of social life is money: how to get it, how to keep it, and how to keep someone else from getting it from you.

On the one hand, there are the systems of cold commerce that drive criminal enterprises in the obsidian-black towers of Manhattan, presided over by well-salaried, faceless administrative hacks working for generic-sounding enterprises known only as the Organization or the Outfit. They send men out on jobs, collect the proceeds, and reinvest in further robberies, drug rackets, and prostitution rings. Unlike the racialized criminals of conventional crime fiction — from the

paisans of Mario Puzo to the African-American and Latino street gangsters of Elmore Leonard and Chester Himes — Westlake’s bad guys are almost uniformly Waspish and unspecific, from the Carters and Fairfaxes of the Parker books to the multinational corporatist eco-villain, Richard Curtis, of Westlake’s recently rediscovered Bond pastiche,

Forever and a Death (2017).

In Westlake’s universe,

money isn’t just something you use to buy groceries and lawn ornaments; it’s a system of governance indistinguishable from the dull professional societies we work for, and from the politicians who do their bidding. It’s not an “urban” thing; it achieves its apotheosis in the suburbs, where the Organization’s CEOs and board members go home to play with their kids. In Westlake’s America,

crime isn’t an aberration; it’s the way things work.

On the other hand, the Westlake “heroes” qualify as heroes almost entirely by virtue of their ability to work outside the big office towers and top-down corporate hierarchies; and

as highly skilled, self-regulating freelancers, their main occupation is to steal money back from the corporate thugs who stole it from everybody else. For example, there’s the racehorse-betting cab driver, Chet Conway, in

Somebody Owes Me Money (1969), who spends an entire novel dodging the guns coming at him from various gangland rivalries for no more altruistic a reason than his desire to be paid what he is owed on the only decent bet he ever laid down. Meanwhile, his dad enjoys his twilight years trying to figure out ways to cheat the life insurance companies, and the girl of his dreams shows up just in time to teach his friends how to deal cards from the bottom of the deck.

Everybody is either a crook or a mark in Westlake’s universe, and the only distinguishing characteristic of the “good” crooks is that they only want to be paid what they are

owed and not two cents more. They aren’t greedy. They don’t steal from other professionals like themselves. They always keep their word to colleagues. And once they get paid, they trot off happily to the next gig.

The “evil” side of the criminal universe, however, is a distinctly Trumpian one: an endless, escalating chaos created by the various competing crooks and gangsters who secretly run things. These stupid, hive-minded, overpaid white guys steal everything from everybody indiscriminately, even each other; then they try to turn everyone who doesn’t work for them into corporate drones like themselves — and if they can’t turn them, they kill them. The only people who survive outside this ruthless corporate world are freelancers, such as Alan Grofield (one of Westlake’s best series characters), a consummate paid-by-the-heist professional featured in another excellent novel,

Lemons Never Lie (1971). (He originally appeared in some of the early Parker books, presumably to keep Westlake entertained while he wrote those humorless, hard, excellent little thrillers.) He always shows up to work on time; he never hurts innocent bystanders; and if he even suspects that any bystanders might be hurt on a job, he quits.

And when each job is over, he spends his hard-stolen money operating a theater-in-a-barn somewhere in the middle of deadly-dull Illinois, where he paints his own sets, directs, and stars in his own productions, bringing art to the vast American television-saturated wasteland. As Grofield’s girlfriend reminds him: “What you do is best.

Taking from banks and armored cars and places like that. That’s not really stealing, because you aren’t taking from people, you’re taking from institutions. Institutions don’t count. They

ought to support us.” Damn straight.

The publisher Hard Case Crime has undertaken a long-term project to recover many of Westlake’s least-known books, and they have already yielded some great and enduring stuff. Besides bringing out the first US paperback editions of

Lemons and the 1962 novel

361 (former nice-guy Air Force serviceman seeks ruthless payback when somebody kills his dad), Hard Case has also published for the first time three long and remarkable manuscripts — suggesting that, hey, Westlake may have actually

misplaced more good books than most of us will ever

write.

In addition to the recently released

Forever and a Death (which shows that Westlake might have transcended the eco-thriller genre as successfully as he transcended the comic caper and hard-boiled detective formats), Hard Case published

Memory in 2010, a longish, noirish, 1960s-era novel about possibly the greatest threat to American “identity” — the fact that there might not actually be one. Paul Cole — another of Westlake’s frustrated artists — gets lost in middle America after a violent altercation with his girlfriend’s husband that leaves him with recurring amnesia. Over several months of struggling to return home to Manhattan, he keeps forgetting who he is and what he wants; he industriously slogs his way into a mindless factory job, a series of mindless new social responsibilities, and a potentially marriage-bound relationship with an interchangeable (and possibly even mindless) new girlfriend. Then, once he earns the money he needs to return to his old life in Manhattan, he launches himself into a new series of mindless routines all over again.

Memory is a funny, microscopically exact picture of the haunting sameness of middle America, filled with the rigorous naturalistic descriptions and compulsions that drive Jack London’s

Martin Eden and Zola’s

L’Assommoir.

But the pick of the Hard Case lot is almost certainly

The Comedy is Finished (2012), another unpublished Westlake novel that is even better than some of his oft-reprinted ones. In some ways,

Comedy is yet another caper novel but set in the divided political world of ’60s America, when all the old lies about American exceptionalism were coming up hard against the ugly, CIA-sponsored geopolitical violence of Vietnam and Central America. (Contemporary United States, take note.) Out of all the several dozen Westlake novels I have read and enjoyed, Koo Davis is probably his greatest comic creation: a Bob Hope–like hack comic whose silly

shtick of cornball USO shows and stand-up jokes about ditzy “flower children” starts to make him feel complicit in the American-Dream-turned-sour.

Kidnapped by a white-bread version of the Symbionese Liberation Army (middle-class white people clearly scare Westlake more than anybody, and the scariest of these privileged terrorists may well be Joyce, a former Brownie, Campfire Girl, and member of the Junior Sodality at her local church — uh-oh), Koo tries to take his situation seriously as a potentially doomed bargaining chip for a prisoner exchange with the FBI, but he can’t resist firing off corny zingers and toilet jokes at every opportunity. Even when he’s being beaten, poisoned, threatened, and lectured on dialectical materialism, he keeps seeing life as an endless comic routine in a country so stupid that it will probably never get the joke. According to the publisher’s notes, Westlake felt this book might read too much like Martin Scorsese’s 1982 film

The King of Comedy, so he stored it away and it was eventually forgotten. But it is a richer, more politically complex, and more moving story — and a hell of a lot more fun besides.

When the final volley of bullets arrives in

The Comedy is Finished, one of the kidnappers tells Koo: “It sounds like the critics found you.” And while it is likely that critics might not have found or appreciated a novel this good even had it been published back in the time it was written, Westlake clearly didn’t care too much about being taken “seriously,” continuing to produce serious-even-when-funny great books in a remarkable career that never ended until he died. Over several decades of calm, passionate literary production, he never wrote a bad sentence or a bad scene, and he produced so many good books that he needed a filing cabinet of pseudonyms just to keep up. Which, come to think of it, may qualify him as that rarest beast of all: the writer’s writer’s writer. There was always too much of him to go around — which means the rest of us have plenty of time to catch up. -

Scott Bradfield https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/donald-e-westlake-the-writers-writers-writer/#!![Image result for Donald Westlake, Forever and a Death,]() Donald Westlake, Forever and a Death, Hard Case Crime, 2017.

Donald Westlake, Forever and a Death, Hard Case Crime, 2017.

The Bond That Never Was

Two decades ago, the producers of the James Bond movies hired legendary crime novelist Donald E. Westlake to come up with a story for the next Bond film. The plot Westlake dreamed up – about a Western businessman seeking revenge after being kicked out of Hong Kong when the island was returned to Chinese rule – had all the elements of a classic Bond adventure, but political concerns kept it from being made. Never one to let a good story go to waste, Westlake wrote an original novel based on the premise instead – a novel he never published while he was alive.

Now, nearly a decade after Westlake’s death, Hard Case Crime is proud to give that novel its first publication ever, together with a brand new afterword by one of the movie producers describing the project’s genesis, and to give fans their first taste of the Westlake-scripted Bond that might have been.

As Jeff Kleeman describes, at length, in his Afterword, the origins of

Forever and a Death can be found in Westlake's treatment for a possible

Bond 18 -- the next in the then-staggering James Bond franchise, at a time when all hinged on the 1995 make-or-possibly-break

GoldenEye. Westlake ultimately didn't get the gig, but used some of the material in writing

Forever and a Death (keeping a Bondesque title, but with no Bond-figure figuring in the story) -- though it was never published during his lifetime.

The opening chapters nicely set the stage, with tiny uninhabited Kanowit Island, a mere two miles across, on the south end of the Great Barrier Reef, being readied, in spectacular fashion, so that it can be turned into an upscale resort by developer Richard Curtis. Some clever engineering by George Manville makes this the testing ground for the application of a soliton to raze everything to the ground -- a wave propagated through the island, breaking up everything solid. And, while useful for this project, Curtis secretly has something much bigger in mind if it works -- the British handover of Hong Kong a few years earlier cost him dearly, and he wants to exact revenge, and a larger-scale soliton would more than do the trick .....

An environmental group called Planetwatch, and one of its leaders, Jerry Diedrich, show up just before the soliton is set off. Diedrich has become a big thorn in Curtis' side:

He's been after me since just around the time I left Hong Kong, and it's me that he wants, not polluters or environmental criminals or any of that, it's me. Most of that Planetwatch crowd is off doing something about the ozone layer or some fucking thing, but he's got this one bunch fixated on me, he's got them convinced it's a crusade and I'm the evil tycoon that has to be brought down. Clearly it's personal -- though Curtis can't figure out why. And his bigger problem is that he does have things to hide, and so Diedrich's constant presence is more than just annoying. And then there's the question of how Diedrich always knows where Curtis is: there must be a mole in the organization, feeding him information.

Kim Baldur is a young volunteer on the Planetwatch boat and, overeager, she goes over the side of the boat in her scuba gear just before the soliton is set off. She can't be expected to survive that -- but she does, and while the Planetwatch ship has to turn tail, Curtis' crew fishes her out. Curtis would rather she were dead -- causing enough legal headaches for Diedrich to keep him off his back for a while -- and since she's not he decides to help her along.

When Manville realizes that girl still can be saved he knows what he has to do -- and that he's making a big and dangerous enemy in Curtis once he does. Stuck on a ship, escape isn't easy -- but Manville and Kim manage to make it to the mainland. They decide, however, that they don't have enough proof to go to the authorities -- giving Curtis time to begin to spin the story his way.

Curtis really wants Manville and Kim out of the way, and he works to arrange that. Meanwhile, Diedrich reëmerges in the picture, too; Kim teams back up with him, while a kidnapped Manville is stashed in the Australian outback by Curtis until he can figure out how to handle the situation.

The story eventually moves to Singapore -- Curtis' new base -- and finally Hong Kong, where Curtis' plan is meant to be set into action. Leading there, a couple of games of cat and mouse continue -- with some of Curtis' henchmen doing some dirty work along the way, though generally with mixed results. Still, the mole in the Curtis-organization is identified, and decommissioned (or rather: put to a different use).

With Manville, Kim, Diedrich, and a helpful Australian policeman on his heels, Curtis still manages to stay a step ahead, and begins to put his plan into action. Will the good guys be able to stop him in time ?

Forever and a Death has its moments -- but they tend to be of the cinematic sort. Although, character-wise, the novel doesn't much resemble a Bond-movie, it remains typical blockbuster action-fare, and from the opening scenes' soliton to the final showdown, most of this sounds like it would works better on the screen. (So also things like the question: "Is the submarine hooked to the bulldozer ?")

Westlake also doesn't manage to keep the focus anywhere long enough. For a while, it seems Manville will be the dominant good guy hero -- but then he's stashed in the outback, twiddling his thumbs. More of a focus on the bad guy might have worked too, but Westlake doesn't go that route either. And the interactions with outside help -- an attorney, the police --, while showing some promise, are also mostly underused. Then there are the minor characters who come to the fore, but Westlake doesn't seem entirely comfortable leaving them there too long. It makes for an oddly paced -- indeed, often somewhat plodding -- novel, all the more noticeably so because it's well over four hundred pages long .....

Forever and a Death could make an enjoyable action-film, but on the page it just doesn't work that well, with even the writing on the by-the-numbers and slightly uninspired side. This is a novel that probably would have worked much better either in much tauter form -- or expanded. At this longish middle length it just feels lumpy. (And while it's a good-sounding title, it's not exactly a great fit for the story itself.)

- M.A.Orthoferhttp://www.complete-review.com/reviews/westlake/forever_and_a_death.htm

bookgasmborg.comThe Crime ReviewDead End FolliesGold Metal FaucetJames Bond MemeKemper's Book BlogKirkus ReviewsPublishers WeeklyPuzzled Pagan PresentsSleuthSayersThe Soap BoxersWarrendale (Detroit) BlogThe Westlake Review![Image result for Donald Westlake,The Ax]()

Donald Westlake, The Ax, Mysterious Press, 1997.For 25 years, Burke Devore has provided for his family and played by the rules. Until now. Downsized from his job, Devore is slipping away: from his wife, his family, and from all civilized norms of behavior. He wants his life back, and will do anything to get it. In this relentlessly fascinating novel, the masterful Westlake takes readers on a journey of obsession and outrage inside a quiet man's desperate world.

The Ax is narrated by Burke Devore. He's married, to Marjorie, and they have two kids in their late-teens, Betsy, who is already off at college, and Bill, . He worked at a paper mill for over two decades, most of them as a product manager -- until he got a yellow slip in 1995, telling him he was going to be let go, part of the company's massive restructuring plan. The transition was a slow one -- five more months on the job, a decent severance package, even continued medical insurance for a while -- but the recovery he imagined, finding a new job, hasn't materialized in the nearly a year since he was let go.

Burke understands: the conditions aren't favorable, the power lies elsewhere, he has little to offer or bargain with.

I do know paper, and I could take over almost any managerial job within the paper industry, with only minimal training in a particular specialty. But there's so many of us out here, the companies don't feel the need to do even the slightest training. They don't have to hire somebody who's merely good, and then fine-tune him to their requirements. They can find somebody who already knows their precise function, was trained in it by some other employer, and is eager to come work for you, at lower pay and fewer benefits, just so it's a job. Burke and his family are still getting by -- Marjorie has two small part-time jobs, for example, which helps. But it's eating away at him, and he's decided he has to be pro-active. Not in the way the so-called experts suggest -- a course in air conditioning-repair is among their suggestions -- and not just by passively submitting resumés (as he's been doing -- even getting the odd interview here and there, only to be denied, again and again). No, desperate Burke comes up with a desperate plan: he has targeted a specific position at a relatively nearby plant, and the fact that it's currently filled isn't a problem: he's going to make sure it opens up -- and, when it does, that he's the best candidate for the spot. First he plans to wipe out the competition -- the similarly-qualified managers who are also hunting for the same kind of job -- and then he'll take out the guy currently in that position. When they look to fill the newly-opened position, he'll be their man. So the theory, anyway.

It's a pretty hare-brained idea, but Burke has thought most of it through, and these are the lengths to which he's willing to go to. And that's what

The Ax is: an account of his controlled but murderous rampage, all just to get his life on course again. Sure he has qualms -- "What have I started here ? What road am I on ?" -- but he honestly doesn't see any alternative. He's been driven into a corner, and this is his only way out.

Despite the outlandish plot, Westlake's novel is mighty impressive. Burke is a difficult sort of character to present, but his cold rationality -- a forced sort of freeze, so that he doesn't let the horror of what he's doing get to him (too much) -- is convincing, and all the more believable when he struggles in confronting several of these men who are, after all, going through much the same thing he is: he can see himself all too clearly in each of them. The rationalizations are far-fetched, but Burke needs to convince himself, since he can't see any other way out. It's self-defense, he tells himself -- he

has to kill:

In self-defense, really, in defense of my family, my life, my mortgage, my future, myself, my life. That's self-defense. It's a thin line, but Burke doesn't cross over to pure psychopath, and part of Westlake's accomplishment here is in how plausible he makes Burke's perverse crusade. Burke is believable as a character driven so to the edge that he's willing to go down this road, weighing the costs to his soul and deciding it's a price he has to pay.

The Ax is an exciting thriller: Burke's plan is clever, but hardly foolproof -- beginning with the fact that if he's going to be using the same gun ballistics matches will quickly point to a serial killer with a very selective target-list. He's forced to take some chances, and he does have his run-ins with the police. There's a good deal of can-he-get-away-with-it tension, nicely handled by Westlake, but there's more to the book, too, including its critique, implicit and explicit, of a capitalist society that places shareholder value so far above any broader sense of community, and thus wreaks havoc on community. (It helps, and adds much to the book's power, that Burke and his victims are -- or were -- all securely middle management and middle class (or, as it turns out, not so securely ...).)

There's also the effect on family, with Burke not realizing just how much his unemployment, and the way it has affected him, has affected his family, driving his wife to seek consolation elsewhere and ultimately pushing her to force him to go into counselling with her, justifiably concerned they aren't going to make it as a couple otherwise. Son Billy also gets in trouble with the law, but here Burke's transformation into a more take-charge kind of guy, more concerned with doing right for his family than simply doing right, turns out to be (at least in terms of seeing that Billy's future isn't ruined) a positive thing: whatever lessons Burke has learnt on his killing-spree haven't made him a better man or father, but they've made him better-suited to take on the challenges of a dog-eat-dog world of winners and losers.

The Ax is a cold, dark, and very well-crafted novel. Westlake is very good at what he does here: this is very good writing, very good plotting, and a great character-portrait, lifting the novel far above mere sensationalist serial-killer fare. Burke Devore is just one of many who has has been devoured by modern capitalist society, but Burke chooses to fight back, the only way he can conceive of. He's decided on his priorities, and he's willing to pay the price (to his soul); that Westlake can send him down this path so convincingly is a terrifying indictment of modern America.

Recommended.

- M.A.Orthoferhttp://www.complete-review.com/reviews/westlake/ax.htm

Crime TimeKirkus ReviewsMystery*FileThe NationThe New York Times Book ReviewNoirboiled NotesPublishers WeeklyTemple of SchlockWag the FoxThe Washington PostThe Westlake Review![Getaway Car Cover]() Donald Westlake, The Getaway Car(Non-Fiction Collection), University of Chicago Press, 2014.

Donald Westlake, The Getaway Car(Non-Fiction Collection), University of Chicago Press, 2014.“‘This is a book for fans,’ Stahl insists in his introduction — the sole misstep of his whole enterprise, because in fact this is a book for everyone, anyone who likes mystery novels or good writing or wit and passion and intelligence, regardless of their source.” ~ Charles Finch,

NY Times Book Review“Westlake was not this kind of writer, or that kind, not a crime writer, or a satirist, or a comedian. He was just a writer, and as good as they come.” ~ Malcolm Jones,

The Daily Beast“Westlake was a hugely entertaining and witty writer. Whether he is writing a letter to his editor or about the history of his genre, he remains true to his definition of what makes a great writer: ‘passion, plus craft.’” ~ P.D. Smith,

The Guardian“He was a storyteller of amazing inventiveness and range, of comic capers and noir thrillers, of manic romps and melancholy tales, of wacky adventures and clever conceits. His novels are set in the America he lived in. If you were to read widely in the Westlake oeuvre, you’d get a better education in the many complexities of American life than you would if you were to spend years studying for a Ph.D. in sociology or American Studies.” ~ William Kristol,

Wall Street JournalSamples from the book:A Pseudonym Returns From an Alter-Ego Trip, With New Tales to TellThe Hardboiled DicksLetter to Pam Vesey, copy editor at Marian Evans [The Daily Beast]“There can be no question of my doing justice to the writing of Donald Westlake, also known as Richard Stark, Tucker Coe, and other cover names. For background you can go to his fine site or to Wikipedia, or this warm appreciation by Michael Weinreb. Here I just want to pay brief tribute to a writer who, like Rex Stout and Patricia Highsmith, seemed incapable of composing a bad sentence. Elmore Leonard gets deserved recognition as a laconic master of language, but Westlake was no less skillful. In some ways he was more ambitious and audacious.”

Read more:

How to write: Professor Westlake is in, by David Bordwell — David Bordwell’s Website on Cinema (2013)

“When I first came across the fictional antihero known as Parker, he was in a hotel room, torturing a man who had tried to murder him in his sleep. I was browsing a specialty bookstore in Greenwich Village that, like most specialty bookstores, no longer exists; I had, by pure chance, picked up a skinny little volume called The Outfit, which doesn’t so much begin as get straight to the goddamned point. It is no secret that the man who wrote the Parker novels deliberately started many of them with the word “when,” thereby ensuring the rising action would not be muddied up with dull things like exposition; I contend that one of the most direct first sentences in the modern history of the novel details a telephone ringing when Parker is in the garage, murdering a man.”

Read more:

The Many Lives of Donald Westlake, by Michael Weinreb – Grantland (2013)

“The Parker novels are but a small part of Donald E. Westlake’s illustrious career. This Grand Master of the Mystery Writers of America penned more than 100 novels and short stories, as well as screenplays. Here’s a look at some of his forays into film.”

Read more:

Parker as Parker: The Long Road to the Big Screen, by Valerie Kalfrin – Word & Film (2013)

Posthumous novels, of course, are not unusual. […] But what about posthumous novels that are neither the last work of a writer recently deceased nor a virtually completed work that, for some reason, wound up in the bottom drawer? Both of the Westlake discoveries are in that category. So two questions arise: Why weren’t they published while Westlake was alive, and would he have been happy to see them published after his death?

Read more:

Westlake Lives! Two posthumous gifts from a master entertainer. — The Weekly Standard (2012)

“Donald E. Westlake was a twentieth-century master of crime fiction. Under the name Richard Stark, one of his many pseudonyms, he penned the legendary Parker novels, including three just brought back into print by the University of Chicago Press this week: Butcher’s Moon (1974), Comeback (1997), and Backflash (1998), each with a new foreword by Westlake’s friend and writing partner Lawrence Block. To celebrate their release, Press publicity manager and Parker masterfan Levi Stahl sat down with Brian Garfield, novelist (author of the cult classics Death Wish and Hopscotch), screenwriter, and an old friend of Westlake’s.”

Read more:

Playing Poker with Parker: An Interview with Brian Garfield (2011)

The Black Tentacle, however, is something a little different. It’s an award we created specifically to recognize a novel that doesn’t quite fit the award description but is so exceptional it merits the highest praise. We don’t expect to hand out Black Tentacles every year. Of all the novels we read this year, there was one book that knocked our collective socks off; one book we have ceaselessly recommended; one book we honestly believe every single person who visits this blog should read and own and buy multiple copies of and give away at birthdays and bat mitzvahs and any other day that ends in “-day.” That novel is

Memory, by the late, lamented Donald E. Westlake.

Read more:

The Kitschies: 2010 Black Tentacle Winner– Pornokitsch.com (2010)

“Westlake’s writing felt like the work of a man half his age, someone still hungry to make it as an author. His storytelling retained its interest right up to the end. Losing James Crumley stung. Losing Gregory Mcdonald was a blow. Losing Westlake? That hurt. Especially since he showed no signs of slowing down in his writing and never lost a step. A rare feat, indeed, dear readers.”

Read more:

Nobody Runs Forever: A Last Good-bye to Donald E. Westlake, by Cameron Hughes – The Rap Sheet (2009) [Includes farewell blurbs from many admiring authors.]

Just before Nobel season in 2006, the Los Angeles Times asked several commentators for prize recommendations. I suggested Westlake for literature: “Enough with honoring self-consciously solemn, angst-ridden and pseudo-deep chroniclers of the human condition. Westlake is smart, clever and witty–a prolific craftsman–and deep. But do the Nobel judges have a sense of humor? I doubt it.”

Read more:

Donald E. Westlake, 1933 – 2008, by William Kristol — The Weekly Standard (2009)

“Crime fiction lost a don of the genre last week: Donald E Westlake, the author of more than 100 hard-boiled novels and mystery capers, died at the age of 75. Westlake’s legacy is not just a library of pulpy page-turners: he had a hand in a pack of classic crime movies, including Point Blank and The Grifters. Chris Wiegand presents a shot-by-shot guide to the best”

See more:

Westlake at the Movies– Photo Gallery, The Guardian (2009)

“Donald Westlake started writing crime novels in 1960 and he made his entrance with a bang: his first one, The Mercenaries, was nominated for the Edgar Allan Poe Award from the Mystery Writers of America, and deserved to be. Between then and his death this past New Year’s Eve, he wrote something like 100 more, won the Edgar three times, was named a Grand Master by the MWA, got an Academy Award nomination for his screenplay of The Grifters, and was called “one of the great writers of the 20th century” by Newsweek. Those are the facts of the matter. What they fail to capture is why people loved the man’s books and why they had the impact they did.”

Read more:

Bloody and Rare by Charles Ardai in The Guardian (2009)

“There is a cliché (and clichés usually become clichés because they’re true) that comedians and comic writers are dark, angry, unhappy souls. Donald E. Westlake, who died on New Year’s Eve of a heart attack at age 75, was the funniest mystery writer who ever lived, and nothing about him, or his work, was a cliché. You wanted him at a party because he loved to laugh, just as he loved to make people laugh. He made it clear that he was never the funniest kid in school, but was always the best friend of the funniest kid.”

Read more:

From Laughter to Tears by Otto Penzler in The Wall St. Journal (2009)

“Lest one confuse prolific output with mediocrity, think again. Westlake came of age during the heyday of the paperback revolution, when quantity was rewarded at a penny a word by houses looking for lurid tales worthy of the racy cover art. With families to feed and deadlines to meet, there wasn’t time to fuss over the right turn of phrase or elongated story lines — or to thumb a nose at a particular genre. During his six-decade career, Westlake wrote sleazy novels and children’s books, penned Oscar-nominated film scripts like “The Grifters” and epic television flops like “Supertrain,” dabbled in science fiction and even cooked up a biography of Elizabeth Taylor. But his best home was always crime fiction, as seen through the fun-house mirror of works written under his real name and by his darker alter ego, Stark.”

Read more:

Under any name, Donald Westlake was a grandmaster by Sarah Weinman in The L.A. Times (2009)

“After watching a bare-chested dentist trekking through the jungle by torchlight to shake a spear at a sunburned accountant in a loincloth, you might think television reality shows were beyond satire. But that would be underestimating the puckish wit of Donald E. Westlake, who died of a heart attack last New Year’s Eve but still leaves us laughing with his final novel, a rollicking crime caper that pulls the pants right off the reality TV industry. ”

Read more:

NY Times Book Review for

Get Real, the last in the Dortmunder Series (2009)

On October 8th [2004] the Private Eye Writers of America gave me their annual Shamus Award [The Eye, Lifetime Achievement Award] at a dinner in Toronto, in conjunction with this year’s Bouchercon. Airplane schedules defeated my plan to be there to accept the award, but I sent along the following acceptance speech, which was read to the group by Bob Randisi. I was not the only one who was there in spirit only. Max Allan Collins introduced me, but he couldn’t be there either, so his astral spirit introduced my astral spirit, or something like that. Anyway, here’s what he said, and then here’s what I said. ~DEW

Read more:

Don receives “The Eye” for Lifetime Achievement— Private Eye Writers of America (2004)

“Simply the best. One of the most accomplished crime writers ever, and certainly one of the funniest, Donald Edwin Edward Westlake was born in Brooklyn in 1933, and rambled around much of New York state, growing up, or at least that’s his story. He was raised in Yonkers and Albany, and attended college in Plattsburgh (Plattsburgh? That’s uncomfortably close to Montreal!), Troy and Binghamton, and finally Manhattan. “None to much effect,” he hastens to assure us.”

Read more:

Donald Westlake– The Thrilling Detective