It is you who now digs through the dirt of years, rearming Megalocnus’s skeleton. You, adding flesh and blood to the bones of your ghosts. You and He, dedicated to reconstructing the Island’s skeleton. You will write that book because there is nothing else you can do. Because the obscure object of desire is winking at you. Because a command runs through you as well.—Fragment from “The Sands of the Wreck,” From the book La forza del destino (Alfaguara, Mexico, 2004). Translated by Emily Woodman-Maynard, here .

Novelist, essayist, and playwright Julieta Campos has employed various genres with formal mastery and stylistic audacity. “Today I feel that I can reconcile myself, at last, with my split identity,” she wrote in the introduction to

Reunión de familia (Family reunion) (1997), a compilation of her early narrative works and one play. Campos’s confession alludes not only to the many genres she has explored but also to the alliance she has wrought between her literary vocation and real life’s call: to better the lives and living conditions of Mexico’s poor indigenous population. In fact, the discovery of a pact between the alchemy of writing and the temptation to modify actual existence appears, in her case, to have smoothed the way for the reconciliation of these two facets of experience often considered contradictory, even adversarial. Yet there is still a third way to interpret this “reconciliation”: the Cuban-born author’s intellectual and biographical paths have led her to recognize that Mexico, her adopted home, is a definitive place in her life.

In early novels such as

Celina or the Cats (1968),

She Has Reddish Hair and Her Name is Sabina (1974), and

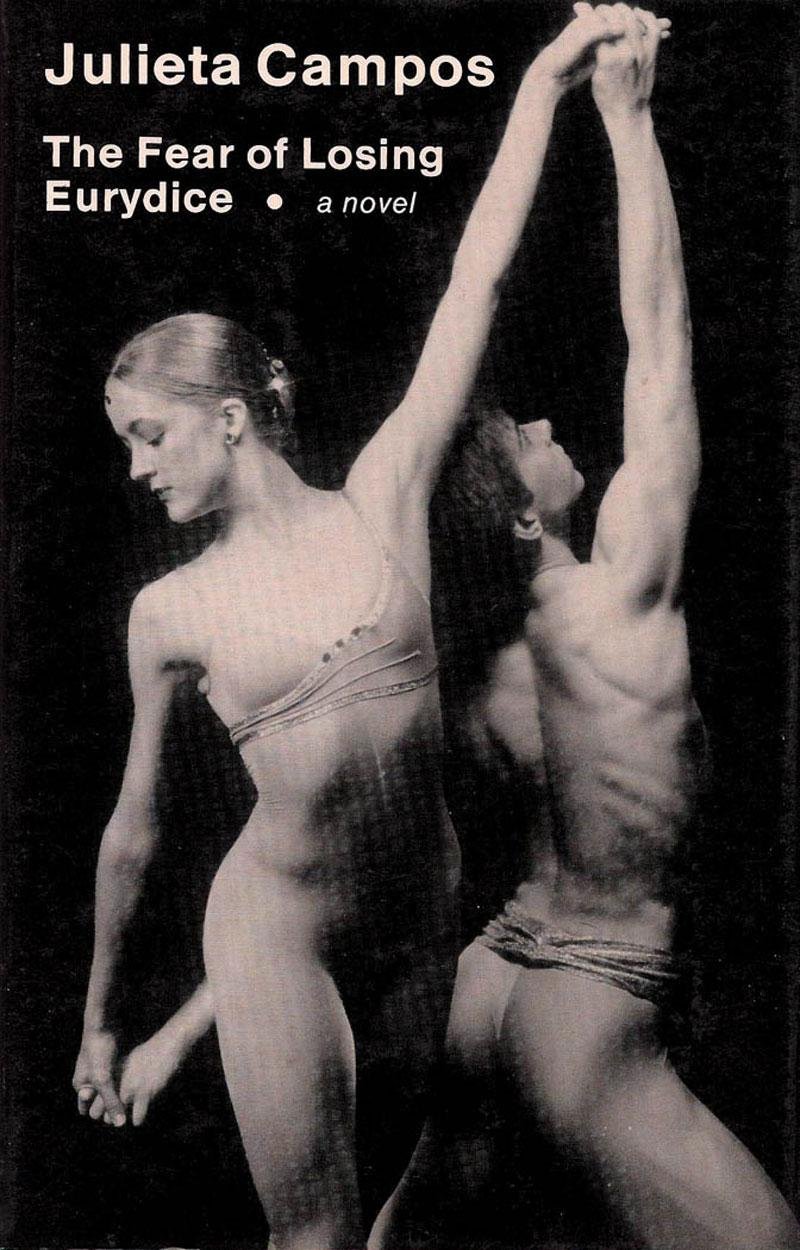

The Fear of Losing Eurydice (1979), as well as in her play,

Jardín de invierno (Winter garden) (1988), the word itself is the central object of a literature fascinated by its own image, absorbed in its own interior resonances: a literature that shies away from storyline in the canonical sense and is instead populated by indefinable characters, all situated in an ambiguous, almost abstract, space-time. Such concerns and interests were unusual for Latin American literature of the time, so wedded to realism or its derivatives. In any case, the essays and articles that Campos produced in this era speak from an awareness of the problems of writing, from a consciousness that explores the less formulated mechanisms of language, balancing many of its preoccupations with a critical eye. Later, distancing herself from these concerns, but without producing a break in the heart of her writing, a new horizon appears in Campos’s work: the analysis of ideas and the exploration of reality. Titles such as

Un heroísmo secreto (A secret heroism) (1988),

Tabasco: An Awakened Jaguar (1996), and

¿Qué hacemos con los pobres? (What Do We Do With the Poor?) (1995) testify to her ample interests. They testify, as well, to her yearning to deeply explore literature and to her determination to make Mexico one of the central axes of her reflection.

In 2003, Campos returned to the novel with

La forza del destino. A book of maturity, wisdom, and formal perfection, it is a continuum of histories and subhistories that aspire to span the world. The novel begins in 1492, in Toledo, Spain, and ends at one point in 1956 and at another in 1991: thus Campos covers the whole legend of the centuries that formed us and conform us as Latin Americans. A book that crosses territories,

La forza del destino is many books: the saga of a continent, a societal saga, a family saga and, finally, the saga of a self striving to spell out—patiently, sensuously—her own experience.

Danubio Torres Fierro Your most recent novel,

La Forza del destino, is a journey to the beginning: a return to your foundational myths, to that kind of personal “archaic sacred” that such diverse writers as Proust, Faulkner, and Juan Rulfo have also explored. It was an unusual return to the novel, after more than 20 years of narrative silence in which you only wrote essays and one play. What happened to you in those years? What does this book mean to you?

Julieta Campos This book is the sum of all that I have learned about life. I know very well that, although I began to imagine it more than 20 years ago, I would not have been able to write it then. It’s one of those books that can only grow inside a person when many experiences from life, and from death and from love, have long sedimented themselves in one’s memory. It is, moreover, a reconciliation with my origins, with the other part of my split identity that points me to Cuba. In the 1960s and ’70s I wrote avant-garde fiction that set up a certain “space and time,” avoided a linear plot, “deconstructed” its characters and avoided a specific storyline.

DTF People have talked about an affinity between those texts of yours and the French

nouveau roman. In effect, they share the same obsession with language and form, with building a certain structure, with a verbal object conceived as an “art object.”

JC You know that my first encounter with the world outside Cuba was when I went to study in Paris in the 1950s, making a short layover in New York. French literature undoubtedly left its mark on me; in that moment France was at the vanguard of literary experimentation. But the first books I read were written by English, American, and German authors: Virginia Woolf, Katherine Mansfield, Elizabeth Bowen. And, of course, Joyce and Rilke. And Thomas Mann. When I was 18 I read

The Magic Mountain, twice: first in English and immediately after in Spanish. Unfortunately I could not read the German. Mann deeply impressed me. I think that

La Forza del destino is reminiscent of

Buddenbrooks, Mann’s great family saga. But if you compare those books, you would likely say that they have nothing in common. Of course, I also remember having read the

Episodes nacionales (National episodes) of Benito Pérez Galdós, the great 19th-century Spanish novelist, during some long vacations in Havana. It was not a conscious influence when I was writing my Cuban saga, but I don’t doubt that every book read long ago is stored away somewhere, in one of those hidden veils between memory and oblivion. But returning to those two very different moments in my narrative work: they correspond to two completely different moments of my life.

The indefiniteness of space, time, and characterization in those first novels speaks of a difficult transition between Havana and Mexico City, and of the laborious elaboration of a link with Mexico. Inside, these spaces fought among themselves, and my perception of time tended to prolong the past into a perpetual present; in my texts, I found an imaginary space capable of sheltering me from the sense of loss, from the exile from Cuba, from the distance that separated me from my parents.

DTF You speak of exile, but your departure from Cuba wasn’t an exile, it was a voluntary choice. There still weren’t even any hints of revolution in Cuba at that time. But you speak of loss and exile. And I would ask you: what happened to the link with Cuba and with your family when the Revolution broke out?

JC I was an only daughter, born in a unique and marvelous city, Havana, which was neither Caribbean nor Mediterranean but had something of Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, and something of Alexandria and something of Cadiz. A city that looked out, from the turrets of innumerable balconies, toward the infinite horizon, keeping watch over the stiff crests of impetuous waves, the color of lapis lazuli. A barrier reef protected the city from the ocean.

Much later I found out that when I was born, there was a sort of dark energy running through the city, threatening and agitated. I went to sleep with the nine o’clock cannon and woke up to the bell from some trolley or the horn from some boat, without suspecting that political passions ran in the streets, passions that had already overthrown a tyrant in order to bring an ambitious sergeant to power: those were the 1930s in Havana.

My mother and my grandmother, extremely loving, isolated me from the commotion outside. Death had visited our house all too frequently: my grandfather and his two sons, my mother’s brothers, were already gone. My own arrival restored life to my grandmother, and for my mother it was almost a miracle to rock that little girl born of a late marriage: it had taken my father, adventurous and frequently lovestruck, 15 years to culminate their engagement.

But I’m not exactly answering your question. Or perhaps I am, because that childhood, overprotected, even a little suffocating, had another aspect to it: my father had transmitted to me his free temperament, his imagination, and his yearning to see the world—his father, also Andalusian, had been a captain in the Spanish merchant marine. All of this explains one of my ambivalences: the desire to travel, which took me to Spain when I was 20, and, at the same time, the desire to remain shut away forever from the noises and risks of the outside world. But beyond the smell of the jasmine and the night jessamine that my grandmother cultivated, the wide world beckoned with all of its attractions and dangers.

The lights of the ships that dropped anchor in Havana’s bay soon began to wink at me. The

Queen Elizabeth transported me, in the end, from New York to Cherbourg. And, in Paris, I came across the Mexican who is still my husband today.

DTF On your first trip away from home, your life changed forever. Could we also say that the Revolution, with its terrible destruction and heartache, further marked your distance from Cuba?

JC We were in Havana, spending Christmas with the family, when the dictator Batista fell. Fidel Castro then entered Havana in an apotheosis of enthusiasm. My two great-aunts compared him with Carlos Manuel de Céspedes and José Martí, the heroes of the fight for independence from Spain.

The enthusiasm was all too contagious, and a desire for freedom filled people’s spirits. But, little by little, daily life began to be filled with restrictions. My father and mother could not come to live in Mexico, as they had planned to: my mother was invaded by a lung cancer that killed her over the course of four terribly slow years, and a year later my father died of a heart attack. When I went to see them a year before my mother’s death, my passport was taken away when I arrived.

During the week I spent at my mother’s side, in her greatly deteriorated state, I was filled with the overwhelming sensation of confinement, of being trapped between walls of water that would keep me there forever. And there was something ominous in the very air we breathed. In mourning my mother’s loss, and my father’s soon after, I also mourned for a style of life and a time lost forever, for something deeply entwined inside myself that remained definitively behind.

DTF And this obviously influenced your literature.

JC While Cuba, in my first texts, became an abstract landscape, never directly mentioned, I was also converting that abrupt uprooting from Cuba into a slow and painstaking insertion into my new Mexican surroundings.

My life split in two: I believe that’s what accounts for the fragmentation of time and space in my fiction of the ’60s and ’70s, and for its fragmented characters that wander about like souls in pain, in search of a tale to find shelter in. It was a liminal fiction that framed the story without ever completing it. But it wasn’t an intellectual or imaginary game. It was a transit along a thin cord, where the right to survive was in jeopardy.

DTF Do you mean to suggest that in that refined literature—those “literary artifacts” that some have considered canonical texts of postmodernism, where lucidity, intelligence and even, I would say, a certain ironic distance, all prevail—that those texts in fact hide something deeper and therefore more elemental?

JC Of course. I experienced melancholy, heartache, and distress for the emptiness of the world in a way that was not precisely cerebral. Only writing allowed me to survive in those years, in the midst of a reality that sent me contradictory signals and seemed essentially chaotic to me. Only writing could impose an order onto that chaos.

DTF You have recurrent motifs and themes: cats, mirrors, Venice, ships, islands …

JC They are all signs with a double meaning: they have to do with the ambivalence between Eros and death. Venice is, or was, the quintessence of imaginary space: the site of the most splendid beauty. And her fascinating labyrinth is infiltrated throughout by the threat of death. Thomas Mann expressed it for all time in the exquisite story that is “Death in Venice.”

DTF Why don’t we talk about what happened to you in the 1980s and part of the ’90s? I asked you about it at the beginning and you haven’t answered me. I believe that the turn your life took at that moment was defining.

JC That’s true. Until that moment I had accompanied my writing with other activities that, in one way or another, were closely related. I translated many books: for years I was a passenger in transit among history and psychoanalysis, sociology, philosophy, even economics. I ended up translating more than 30 books. I also lived the academic life, teaching in the National University, and I wrote for cultural supplements and magazines, like

Plural,

Vuelta, and the university’s own

Revista, which I began to direct in 1980. Octavio Paz convinced me to coordinate activities for the PEN Club, and it occurred to me to put together a bulletin recording the numerous attacks against freedom of expression, including imprisonment and worse, suffered by men and women of letters all over the world. I traveled extensively throughout Latin America, the United States, and Europe. We always returned to Paris, the only city where, after Mexico City, we felt at home. In 1975 I returned to Havana. I didn’t like what I saw, what I heard—and what I didn’t hear. The island had become ostensibly silent.

DTF You still haven’t answered my question.

JC I’m about to. In 1982 another dilemma began to disturb me. A book of a different nature began to insinuate itself in my mind, and it didn’t have anything to do with my previous fiction. I had my first draft and I felt that I should have another look at

Buddenbrooks. This new book, while it was still scarcely a distant melody that came closer and closer, would end up invading me and overflowing me. But this would occur many years later. At that moment the idea both tempted me and scared me. As if some arcane prohibition forbade me to attempt a narration as ambitious as the one I began to glimpse, one that, moreover, had to do with the other part of my identity that I had guarded under lock and key for years, in an impenetrable corner of my memory.

Well, just as my writing was about to take a leap toward another dimension, it was my life that took the leap. My husband announced that he was going to run for the governor’s seat in his state, and I grew pale. What did the writer inside me have to do with a political campaign? Before my husband had entered academia (he directed the School of Political Science at the National University), he had served in the Senate for 10 years, but that had not altered my daily life. This, on the other hand, meant spending six years in Tabasco, in the southeast of Mexico, on the outskirts of everything: friends, the literary scene, the magazine, the PEN Club. My deep-rooted distrust of power foretold an uncomfortable stay in the humid tropics. But there was no time for doubts. Once again I was uprooted, this time from Mexico City, where I had come to feel a sense of belonging.

DTF As editor in chief of

Revista after you left, I brought materials to you in Tabasco, where you also participated in cultural activities. But Tabasco was something completely new, a real shock for you.

JC Yes, it was the unexpected. That untimely circumstance changed my life.

I had explored, almost obsessively, the motives of the desire to write. I yearned to observe myself in the process of gestation that leads to a book’s birth. It was even the theme of my award-winning novel

She Has Reddish Hair and Her Name Is Sabina. My own experience had suggested to me that one writes novels in order to impose an order on life’s chaos, in order to satisfy in the imagination what cannot be satisfied in our always insufficient realities. Novels are written because we need to fill in the empty spaces. The writer only trusts in the alchemy of writing in order to recompose reality. She or he doesn’t believe in the possibility of transforming it in any other manner. Nor does the writer aspire to do it another way.

What happened to me in Tabasco was a strange discovery:

doing can be intoxicating. I was discovering, at the same time,

the other Mexico: the country of extreme poverty, of absolute scarcity, of the inability to satisfy the most basic of necessities.

From town to town, in scorching treks through the countryside, I suddenly came across the faces of the other: the dispossessed. I began to learn to read reality in another way.

DTF And the urgency to write began to fade away.

JC You’re right. That’s what happened. I allowed myself to become trapped in another story: I stopped hearing only my own desire to substitute the world’s emptiness with a parallel world, the imaginary one, and I threw myself into a risky but fascinating enterprise: to better the conditions and lives of the poorest of the poor in Mexico, the indigenous. Doing, as I said to you a moment ago, can be intoxicating, above all when one begins to understand that one’s own action also involves the capacity to induce action in others, in those who, deprived of so much, have arrived at the saddest of conditions: that of losing confidence in themselves. Then these people begin to have names and faces; they stop being statistical data registered on some document or in some book.

DTF What happened to you in the ’80s was that you discovered another Julieta.

JC I discovered

fraternity—but not as an intellectual concept; not like a statement of some declaration, prefixed but still abstract, about the rights of man. It was an impassioned existence that lasted almost six years. Learning to listen is a fabulous education in sensitivity. I learned the value of all that we have and take for granted without realizing that, in such an unequal and unjust world, having these things is a true privilege: the possibility of nourishing ourselves, of curing ourselves when we fall ill, of living in a comfortable environment, of educating ourselves, of having access to culture. By a stroke of fate, the misfortune of the poorest didn’t befall us. And, by another stroke of fate, in a given moment I was in a situation where I could ameliorate some of that dissonance, some of the moral scandal that has accentuated itself so greatly in our days: the enormous distance that separates a few isles of prosperity, where scant numbers of us live, from the ocean of need where the vast majority scarcely survive.

DTF You stopped writing during those years, but the writer was still there, crouched in waiting all the while. Observing, and something more than that, because you promoted the unique experiment that was the Laboratory of Peasant and Indigenous Theatre.

JC And it was fantastic to see how, in those communities hanging from the sierra, the people knew García Lorca’s

Blood Wedding by memory, and one could find a young woman, with her child in her arms, or an enthusiastic grandmother, reciting in low voices, as if they were praying, the actors’ lines; there in the open air, in the midst of the hills and the jungles, in an unbelievable natural stage, they relived the Granadine poet’s tragedy, making it their own, and they confirmed once more that art, true art, has no boundaries, but is universal.

DTF And that was clearly demonstrated when the Laboratory came to New York, and then to Granada and later Madrid.

JC So it was. I remember the reaction of Joseph Papp, that man who was himself an institution of the New York theater world. As part of the Latino Festival, which Papp sponsored, the 140 Tabascan Indians were invited to New York. It was their first time abroad. Papp had tears in his eyes when he declared, “It is one of the best groups that I have ever seen.”

The following year, in Oxolotán, he was more explicit. Look, I have the press clipping: “It is a superior work, comparable to that of any theatrical work in the rest of the world. And, at the same time, it is something exceptional in the world, it has an enormous reach, because it breaks the boundaries of theater by creating the feeling that there is a future to people’s lives, without resorting to any political discourse.” And he said more. He said that surely a spectator in the Globe of Shakespeare’s day would have felt something very similar to what he was feeling: “One can feel that he is contemplating the totality of a nation,” he said. What do you think of that?

DTF I think that I missed something very special.

JC You missed it because you left Mexico, just then, to go and live in Buenos Aires.

DTF I remember the commentaries that appeared in the Spanish press; you know that I read

El País no matter what part of the world I happen to be in. The group presented

Blood Weddingin the Casa de Campo in Madrid, also in open air, after passing through Granada, where García Lorca lived and died. I haven’t forgotten that they described how, when the piece ended, the audience—an audience that included Isabel García Lorca—waited a few moments in expectant silence and then gave a standing ovation.

JC Remembering all that makes me very nostalgic. Trying to measure the time that has passed since then makes me feel a little dizzy. It’s been almost 20 years. I don’t dwell on it frequently. I almost prefer to forget it. As if that part of me had to die a little in order to continue forward, in order to live what came afterward.

DTF You live each era with a rare intensity. You live your ambivalences in the same way.

JC Perhaps what has saved me is that the dilemmas of my ambivalences have not been irreconcilable. After Tabasco it took me a while to recover the use of the word, the practice of writing. For one year, in 1990, I had to play a very different role: that of the wife of the Mexican Ambassador to Spain. It was not pleasant. I lost a lot of time in receptions and other innocuous frivolities—not all frivolities are such, I must add.

But I also took advantage of that distance in order to take up the thread of that old project that had been lying in a drawer for 10 years. The idea needed some time to mature, and I cooked up another two books in the meantime.

DTF One was

What Do We Do With the Poor?, a tome of almost a thousand pages, where you carry out a thorough investigation of how poverty is passed down from generation to generation in Mexico, since before the Conquest up to the present day. You also wrote another book, much shorter, where you describe your experiences in Tabasco; it seems to complement the first.

JC It does. It was my way of reconciling, in this case, one of my ambivalences. I had to articulate all of that and also establish some distance from it, in order to take what had emotionally happened to me—and then had left me with a void in its wake—and turn it into reflection and analysis.

I had to reconcile my yearning for tangible action with my vocation as a writer. And I had to submerge myself in the depths of the Mexican part of my identity, to finish paying off that debt. Only then could I fully assume the other part, the Cuban, and write the book that was awaiting me.

DTF I believe that your life has been marked by a constant alternation between reason and passion.

JC I would say that I have spent my life trying to reconcile the one with the other.

DTF And succeeding.

JC At times.

DTF In the prologue to

Family Reunion, the 1997 book that compiled all of your fiction from those earlier decades, as well as your play,

Winter Garden, you consider the cycle finished: you speak of a completed trajectory and, at the same time, of a starting point. You announce that you have begun a long “legend of the centuries” that you started 15 years earlier, and that was insistently knocking on your door. It took you seven years to write that book,

La Forza del destino.

JC More than 20 years ago that long story began to sketch itself out like a vague object of desire. Or rather, a melody started to configure itself that would later become a novel. An endless stream of Cuban voices, from memory’s past and from the present, began to besiege me. I consulted genealogies. I resorted to archives.

DTF But the book isn’t, properly speaking, a historic novel.

JC Fiction is nourished by an unforeseeable link between what was and what could have been, and history indirectly influences the characters. A book of genealogies opened the door for me to the field, immensely open and immensely hermetic, of the past. To my astonishment and curiosity, faces began to accompany me, the voices and gestures of the 14 generations that would eventually produce my mother and that, in the most recent index, were nothing more than names and surnames, dates and offices.

DTF In your novel, the family that settles in Cuba with other founding families at the beginning of the 16th century gradually becomes linked to the history of the island. The references to a History with a capital

H are impeccable, but what matters to you is finding that place of intersection where a collective destiny and the destiny of one or more individuals coincide.

JC “Tomorrow began a thousand years ago,” as Faulkner once suggested. By writing I suddenly discovered that I had as many memories as if I had just turned 500. Everything that has been, in one form or another, continues to exist. The rumors locked in the archives are not rumors of death but of life. Sometimes listening to the dead permits us to better understand the living. As the novel began to take shape, all of these discourses, or voices, started to come to the surface, voices that had once inhabited the island: the voices that one authoritarian voice—the voice of a dictator—had tried to silence. Because in Cuba they have attempted to cancel the past, as if history had begun on February 1, 1959.

DTF The book begins with a great chorus, a wall of discordant voices making their way through the fog: the voices of the living are mixed with the voices of the dead. This overture follows a choppy, almost panting rhythm. I can’t avoid musical analogies, especially when the title refers to an opera by Verdi.

JC Only when I had finished the novel and was writing the 70-page overture—a section that seemed to impose itself upon me and almost write itself—did I realize that that was the only possible title for the book. Over the course of seven years many titles occurred to me, but suddenly, among that tide of voices, one swelled up that jokingly alluded to a fantasy that, starting in the 19th century, many Cubans entertained: the fantasy of being the Island of Utopia, that privileged space for a transcendent vision. There, they would construct a democratic republic that would be an example for the rest of Latin America.

That fantasy, nourished especially by Martí at the end of the 19th century, became fertile ground for another Messianic figure in the middle of the 20th century, who would embark the island on a perilous adventure that would end in a great wreck. I refer to Fidel Castro, of course.

DTF But fate has many other implications in your book. It is one of its great themes and, in one way or another, it acts upon the lives of your characters.

JC Without doubt. Fate is something that we humans feel without having to ever rationalize it: fate—wretched and senseless fate, capricious fate—makes and unmakes the lives of individuals and nations.

DTF Would you consider time to be the other great theme, the other melody that unfolds throughout the book?

JC Time, fleeting and irreversible, is what allows fate to become master of the stage. Everything in this novel, or almost everything, occurs on board an island that sails at the whim of the wind, courted or besieged by the sea. Cycles repeat themselves in the births, lives, and deaths of many characters. There is always the incessant melody of time: time that is extinguished, time that is reborn. In a brief lapse between birth and death, every human fulfills his or her destiny—or attempts to refute it.

DTF La Forza del destino is diametrically opposed to your earlier novels. It is situated in what we could call the classical canon of the novel, which we as readers most enjoy: a continuum of plots and subplots that aspire to include the whole world, so that one book becomes many books.

JC I like to think of it as a sort of

A Thousand and One Nights of the largest of the Antilles.

DTF Do you like to picture yourself as a sort of Scheherazade?

JC A little Cuban Scheherazade? The truth is that all of us who write repeat the ritual of Scheherazade: by telling stories, we seek to delay death another day. But I know very well that this is just another fantasy. -

Danubio Torres Fierro https://bombmagazine.org/articles/julieta-campos/

Connelly is a former British diplomat who is now a literature professor. Extravagant Stranger is a slim book – 100ish pages – but it offers a thorough-seeming look into this non-unexceptional life. From birth to school to the death of parents to narrowly-avoided terrorist attacks to a return to education to fatherhood to the collapse of a relationship and then onward to a fantasised death, this is a “memoir” in both a fresh AND traditional sense – even though the writer is still alive and still writing, he maintains the cradle-to-grave narrative that autobiographic writing usually – by necessity – lacks. (See Christine Brooke-Rose’s Life, End Of as another example of a book attempting to write ones death while alive.)

The book, to me, felt more familiar than its description led me to expect, and I would comfortably slot it alongside other educated, literary, flaneur writers of the now such as Teju Cole and Ben Lerner, and I mean that as a compliment. Though both of these writers have their fair share of detractors, they’ve both won many plaudits and awards, and this inner-literary-male trope is something many people love. We slip in and out of Connelly’s life, into and out of his personal history and his present, and we learn lots about him, but we also learn lots about the world he sees. He speaks about Shakespeare at length, and there is also a gorgeous piece about Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne, which I unexpectedly found deeply moving, and emphasised the comparison with Lerner (who writes a great deal about art, if you don’t know his work). That piece is called ‘Let’s go to Bernini for this one, 2010’. But is it a piece, is it a chapter, is it a poem? It’s difficult to know (like Pond by Claire-Louise Bennett).

Almost all of these pieces work on their own, without context – this could be a collection as well as a singular piece. Everything here is connected to a life, but due to the strange, international, twists and turns of Connelly’s existence, they could be taken from several. Most people don’t do as many things as Connelly has done in his life, and nor are most people as able to write as lyrically (within prose) on so many different topics. King Lear seeps into many pieces, as does Julius Caesar (especially in the parts set in Rome), but despite these recurring, weighty, references, at no point are we asked to read Connelly’s life as tragic.

Some highlights:

- ‘To all the mothers who weren’t’ is a moving piece about being slapped by ones mother when an adult;

- ‘A Walk in the Park, 2012’ is a heartbreaking break-up piece (my repetition intended);

- ‘Dentro’ is a disgusting and hilarious piece about being a buy-to-let landlord taken for a ride.

These are prose poems about growing up then about growing old, they are about the pains of physical decline (including incontinence) and the joys of physical pleasure; there is gluttony and sex and adventure here, there is wit and sadness and avoidance and guilt. Extravagant Stranger is not a long book, but it is an intriguing and exciting memoir offering a window into the life of someone who has not lived a conventional life.There are some absences if considering this as a memoir, chiefly how Connelly shifts from an ordinary lower middle class childhood to an international life of intellect, admin and travel, but I don’t suppose it matters much. This book isn’t being sold off the back of who Connelly is, but rather how he expresses what he has done. I have not come here to learn about a man, but to read an evocation of a life, and in that regard this collection of short, prose, pieces achieves everything it sets out to do. I laughed, I cried, I felt transported, I want to visit Rome (again) and India (never been), too. These travelogue snapshots are deeply evocative, and very exciting, and ignoring Connelly’s troublesome decision to self-identify as a “global scalliwag” (sic and vom), I’d be keen to read more of his work.

The comparisons with both Rimbaud and Ian Fleming make sense, though neither of these emphasise the point I inelegantly make above – Extravagant Stranger is a book that feels very contemporary, very now. It is between genres and styles and in a space where a lot of attention is being paid. Connelly has lived an interesting life, and evokes it in an interesting way. Worth a look. - scottmanleyhadley

https://triumphofthenow.com/2017/05/21/extravagant-stranger-a-memoir-by-daniel-roy-connelly/