Anne Boyer, Garments Against Women, Ahsahta Press, 2015.

www.anneboyer.com/GARMENTS AGAINST WOMEN is a book of mostly lyric prose about the conditions that make literature almost impossible. It holds a life story without a life, a lie spread across low-rent apartment complexes, dreamscapes, and information networks, tangled in chronology, landing in a heap of the future impossible. Available forms—like garments and literature—are made of the materials of history, of the hours of women's and children's lives, but they are mostly inadequate to the dimension, motion, and irregularity of what they contain. It's a book about seeking to find the forms in which to think the thoughts necessary to survival, then about seeking to find the forms necessary to survive survival and survival's requisite thoughts.

“Here Anne Boyer accounts for a form of life—form of life of a woman in this century living in Kansas City apartment complexes or duplexes with names like The Kingman or Colonial Gardens, form of life of a low-rent, cake-baking intellectual parenting a Socratic daughter, form of life of a person whose body refuses to become information or pornography, which are the same. These are the confessions of Anne Boyer, a political thinker who takes notes and invents movements, social and prosodic.

Ta gueule, Rousseau.”

—Lisa RobertsonAnne Boyer’s new book of poems,

Garments Against Women, is a subtle feat of poetic

mise en abyme. She conceptualizes the daily into the philosophical and, thankfully, collapses the philosophical into the quotidian. With her lyric prose, she does not spare words—there is no fear of that sort of economy here; and her language patterning is reflective of the template one might use for sewing: This is two-dimensional so that you may make of it something three-dimensional, something to walk away with, to cover you. These poems collapse her world perfectly onto the page, and in reading them, they become again the uncollapsed world—like a three-dimensional rendering of a mise en abyme painting, each frame falling into the next like an accordion: in and out, in and out (until it slips, beautifully); the music produced may not be perfectly in tune, but it is amazingly attuned.

Boyer’s work is a grand taxonomy, exploring not only what is and what is done, but also what is "not." Take, for instance, her poem "What is 'not writing'?" where she runs lists across the page, densely populating the spaces between with commas. She makes extraordinary the ordinary, and when proffering the obvious, makes us realize how often we miss it: "There are years, days, hours, minutes, weeks, moments, and other measures of time spent in the production of 'not writing'" (44). In her observance of the world, she makes visible what we often keep invisible: "Monuments are interesting mostly in how they diminish all other aspects of the landscape. Each highly perceptible thing makes something else almost imperceptible. This is so matter of fact, but I’ve been told I’m incomprehensible ..." (4).

And in her seeing, the very real world of women up against and among men, women writers among men, women seers among male logos, becomes even more frustrating, more poignant, surprisingly feels more unfair and unequal and angering than a feminist manifesto calling for radical action (okay, maybe that’s what certain of these poems are, but they are so beautifully quiet in their call). The naming of things, and the power therein, grows monstrous in its ability to, alone, validate things in their existence:

Despite the reality of the sky, that it is blue, a woman with an interior is trumped by a man with an exterior or that is what I read in the notes: even the color of the sky is stable only as long as it has a man’s proof [ ... ] I suspect, like many humans in this culture, I have seen more commands of men that I have seen the sky itself. (49, 50)

Boyer’s writing is eloquent in its matter-of-factness, though facticity here is bent, slanted, so that the solidity and confidence of the known sloughs off like skin, exposing the subcutaneous. It is here that we encounter "the problem of what-to-do-with-the-information-that-is-feeling" (3).

This book is evidence of escape. Escape in the sense that some constructs are built for leaving behind, while others may be rooms we cannot, without, be. Boyer, master builder, puts together words, and designs this:

One imagines that one can escape a category by collapsing it, but if one tries to collapse the category, the roof falls on one’s head. There a person is, then, having not escaped the category, but having only changed its architecture. Once it was a category with a roof, now it is a category in which everyone is buried in the rubble made of what once was a roof over their heads. (51)

The "what once was a roof" over our heads becomes new rocky terrain beneath our feet. Floors and ceilings are different and yet radically the same—it is about position and perception. Both are protective planes for the extremities that contain us. Yet what Boyer targets is the ways in which women, specifically, are even further contained.

"Everything in the world began with a yes," wrote Clarice Lispector (

The Hour of the Star, 1977). That was a very long time ago, however, and Boyer understands that things aren’t so uncomplicated anymore: she writes, "the subsubsubcategories of a whatever yes" (86). There is such depth to what is expected—if only it was mind boggling. What it seems to be is mind numbing: "Every morning I wake up with a renewed commitment to learning to be what I am not ... No more jumping ahead, rebellion, daydreaming" (26). And that the complicated nature of our universe and the social structures in our small world(s) are layered so that the strata cannot be exhibited and witnessed in a cross section alone—that too much is held in the spheres themselves; too much is potential-to-be, and that is fragile: "To refuse a bookkeeperly transparency is to protect the multiplicity of what we really want" (36).

Boyer’s poems are simultaneously building to expose and cracking mirrors and breaking pattern, and the things within the frames are being moved outside. Because that is where the world really is (even interiorly). Reading this collection put me in mind of a recent essay by Christine Koschmeider:

I refuse to talk about happiness, for happiness has far more powerful advocates at its disposal: Food industry, health industry, entertainment industry, each of them offering applicable products to carry us towards happiness [ ... ] No, I’m not jumping for the happiness-stick. I want to talk about freedom. The freedom to select and pursue one’s happiness. (

"Blame Me!," Christine Koschmieder)

Boyer and Koschmieder seem to understand that seeing beyond what has been built for us (this "us" means all humans), what we have advertently and inadvertently built, what we have consciously fought against building, and what we have failed to rail against—that this architecture of form and function needs to loosen into so much malleable, breathable mesh. Boyer writes,"a catalogue of whales that is a catalogue/ of whale bones inside a catalogue of garments/ against women that could never be a novel itself" (86). This Steinian moment offers the chance to break the boning in our corsets, to bust out of the constructed exoskeletons that have been sewn into our culture, our economics, our lives. It is a confinement that can feel like we have been placed into the abyss. There must be freedom to select and pursue an uprising.

Michaela MullinFew writers today feel as urgent as Anne Boyer. Who else toils so originally to open a futile door out of a room full of literature leading, impossibly, to a negative space? I feel as if I read her book at a poet-stuffed party and then looked up to find the door slamming in the wind, the cake vanished, the war happening live on TV, and the poets gone. She hadn’t done away with the poets, and I hadn’t forgotten about them. But something had changed with the architecture.

Beckett once spoke to an interviewer about art turning away from itself in disgust. “And preferring what?” the interviewer asked. “The expression that there is nothing to express, nothing with which to express, nothing from which to express, no power to express, no desire to express, together with the obligation to express.” Boyer’s concerns aren’t exactly Beckett’s, and yet she shares much of the same paradoxical impulse. In her new collection, one essay/prose poem is called ‘Not Writing’, another is ‘What Is “Not Writing”?’, another is ‘A Woman Shopping’, in which she imagines writing the book

A Woman Shopping—“this book would be a book also about the history of literature and literature’s uses against women, also against literature and for it, also against shopping and for it”—all part of an actually existing book called

Garments Against Women.

Garments are literature, and literature is garments. Both contain, both obscure, both are seemingly open and apparent, both are imprisoning and appealing, and both are against women. The problem is how to continue to operate within them. The book begins with two black pages and large white text demanding “WHO EATS IN A CAGE? OR WITH A CAGED MOUTH?” An epigraph from Mary Wollstonecraft follows, describing a bookish woman who writes “rhapsodies descriptive of her state of mind”, to “perhaps instruct her daughter, and shield her from the misery, the tyranny, that her mother knew not how to avoid”. The misery and tyranny, in part, is in the historical injustice of literature, and Wollstonecraft’s character tries pointing a direction out, while being aware that for her an escape is impossible. In the postscript, a similar note is struck—Boyer dedicates the book to her daughter, “who has allowed me the possibility of a literature that is not against us”.

Garments Against Women is a dispatch from a cage, but the possibility of an exit, of subverting the mock-eternity of literature’s historical conditions, is what gives Boyer’s book its urgency, its paradoxes and its shape.

Lisa Robertson, a poet from Canada, captures the oblique rigour of Boyer’s writing; on the back of the book, she calls Boyer a “political thinker who takes notes and invents movements, social and prosodic”. A political thinker who invents—what is foremost on display in her writing is logic. It’s a dream logic—displacements, condensations, reversals—and a Marxian one, in which things are always turning into other things. Happiness, pornography, literature, photography and information become scrambled concepts, and the rest of the world falls into a simile-d relational order: “writing is like literature is like the world of monsters is the production of culture is I hate culture is the world of wealthy women and of men”; “epics are the dance music of the people who love war”; “movies are the justice of the people who love war”; “information is the poetry of the people who love war”; “that feed is your poem”; “the flaneur is a poet is an agent free of purses, but a woman is not a woman without a strap over her shoulder or a clutch in her hand”; sleep is dreams is gossip, architecture or civic planning; shopping is a woman shopping; garments are literature; transparent accounts are literature; and “the fin is not a fin of a shark at all though it is a reproduction shark fin strapped on a boy’s back”. A political thinker who invents.

![Anne Boyer]()

Boyer’s is a political imagination, but aestheticised: “What at first kept me enthralled wasn’t justice, it was justice-like waves, and a set of personal issues, like the aestheticization of politics.” Sometimes her prose gives way to lists, as if only in minute specificity can meaning emerge, or as if only in specificity can she attain the right amount of vague complexity, channeling the aleatory, stringing together an unclear life. She claims she considered writing a treatise on happiness, “but only as a kind of anti-history”. “For,” she goes on, “who better to consider sleep than an insomniac?” Part of the anti-book negativity of Boyer’s project is how many shadows of unborn books keep flitting around. Included here is a memoir that’s not a memoir that is a memoir. (“Memoirs are for property owners.”) Included also are scenes from the unwritten book

A Woman Shopping: “Lavish descriptions of lavish descriptions of the perverse or decadently feminized marketplace, some long sentences concerning the shipping and distribution of alterity.” She doesn’t write

Leaving the Atocha Station by Anne Boyer or

The German Ideology by Anne Boyer but she would like to write

Debt by Anne Boyer. And she does write

many small books using methods and forms popular and unpopular with my contemporaries. Among these books was a book of my terrors, a book of my dreams, a book of imagined things, and a book about the rabbits in the yard. I wrote a book for computers with voices. I wrote a book based on euphonious sounds. I wrote a book that was a universal novel. I wrote a book for an avant-garde collective. I wrote a book of traumatic facts. … I wrote this memoir that you are reading, then I wrote a book that was a history of the future in advance of itself. I wrote a book that was the story of a prostitute who walked the streets of Google earth. I am now finishing a book: it is called ‘the innocent question’ or it is called ‘garments against women’ or it is called ‘this champion: life.’Eventually, so many books appear and vanish you lose track of where one stops and another begins.

Garments Against Women is a work in eternal progress, a physical book trapped by covers which nevertheless continues its proliferating self-sabotage. Meanwhile, any notion of books as physical objects collapses. Meanwhile, you forget what book you’re reading.

Some of the most wonderful writing I’ve read on happiness occurs in these pages. Boyer becomes sick, a misery remedied by mixing pills and adding Frost & Glow to her hair. She remembers misery and yet isn’t quite miserable anymore, and it’s in this narrow window that she glimpses happiness. “I dressed a young man in a leopard fur coat and sent him walking through the neighborhoods like that. There was a rising interest in tango dancing. I allowed myself to eat liberal amounts of fresh fruit.” This, I think, is where writing can really delight: a portrait of a miserable person in slightly happier times.

The pieces are short, the book is slim, and it becomes obvious that writing this book took a huge amount of life. There is, after all, a memoir,

Ma Vie En Bling: it takes up 30 mostly blank pages. In the memoir, life shows through movement, through drift. It’s a large, melancholy, poetic life—“the frame of poetry”—without any whiff of romanticism. (“The syntactical evidence of poetry without the frame of poetry is a crime which is much more criminal. Or rather, if it is not in the frame of poetry, poetic syntax is evidence, mostly, of having no sense.”) She lives in apartments named The Kingman and The Franklin Court; she has ideas; her daughter has ideas; she struggles against systems and geography; she works, writes, bakes, goes to China and many American states; she watches a dove die and seasons change and climate change progress and she stands at the edge of cities and economies. It’s a full life, ongoing and tied to politics, economy, history, and the book improvises around this chord. A Walserian trudge through the snow, but with the possibility of a new ending. (From the title piece: “To go to work and work all day and go home / to sleep to get up the next day to go to work / and then to think ‘that was walseresque.’”) Like in Beckett, the modesty and difficulty of carrying on becomes a major theme. A paragraph in the memoir ends like this: “You see I was a woman who took notes. Everyone was very kind and wanted to help, but in order to be clear about it, I will tell the story like this: it appears that she refused the ladder, but in truth she refused the rope.”

And yet this is just half a point: the book implies waves of lived experience through the continuation of life, yes, but also through the tightness of logic, the sharpness, the stunning stretched coherence of these brief pieces. The book reveals labour, but not necessarily the labour of writing: the labour of not writing, perhaps, of tranches of time spent thinking without a notepad—“the words of a restive me, sitting motionless for a year”. You can sense the pauses, the accumulations of ideas. Ideas distill into figurative parts, permutated together in logical relation, and then solidify back into ideas, all in the span of a few airy pages. ‘The Open Book’ employs as its figurative parts “transparent accounts,” kept transparent in the service of profit, along with the individual tallying the accounts, tallying also in the name of profit. The individual has two choices: to tally transparently, in the service of some larger corporate profit, or to steal, for her own individual profit. But maybe someone will discover a third option, Boyer imagines, outside of profit’s circumscriptions—what if she works not for some larger social logic but for herself? Here, at the piece’s end, the figurative parts sharpen: the transparent account becomes also literature, which likewise presents itself as openness and truth, its value supposedly clear, and which must be dealt with through negation, through denial and “conspiracy” and oblique independent motive. Here, in condensed figurative form, is Boyer’s project: the impossible possible revolutionary desire of undermining the smug transparent history of literature through a new literature, “off the books”. She’s given up literature to sew a garment that’s an anti-garment. Her tools? Logic, poetry, a sewing machine, and all of these things’ negations. -

William Harris

In this textual hybrid of rhythmic lyric prose and essayistic verse, visual artist and poet Boyer (The Romance of Happy Workers) faces the material and philosophical problems of writing—and by extension, living—in the contemporary world. Boyer attempts to abandon literature in the same moments that she forms it, turning to sources as diverse as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the acts of sewing and garment production, and a book on happiness that she finds in a thrift store. Her book, then, becomes filled with other books, imagined and resisted. "I am not writing a history of these times or of past times or of any future times and not even the history of these visions which are with me all day and all of the night," she declares, and concludes that "writing is like literature is like the world of monsters is the production of culture is I hate culture is the world of wealthy women and of men." This text is in constant upheaval, driven in equal measure by the poet's insistent questions and by her refusals, as she recalls "the days when we believed information." Of course, Boyer cannot resolve the problems she faces, but in providing new frameworks to think about them, her writing rewards readers with its challenges. -

Publishers WeeklyAnne Boyer’s Garments Against Women is a deeply intellectual book with purpose; it widens the boundaries of poetry and memoir as we know them, in ways that can be especially useful for people who distrust these genres. Boyer begins with a quote by Mary Wollstonecraft about a woman for whom reading, and more importantly, writing is “the only resource to escape from sorrow,” especially if she can create writing that “might perhaps instruct her daughter, and shield her from the misery, the tyranny her mother knew not how to avoid.” Can writing do this? Boyer begins to address this challenge in the collection’s first piece, “The Animal Model of Inescapable Shock,” which invites us to turn our attention to the social engineers of our time, with a hope to escape their tyranny:

“the animal model of inescapable shock explains why humans go to the movies, loves stay with those who don’t love them, the poor serve the rich, the soldiers continue to fight, and other, confused arousing things.”

But before the reader has a chance to ask, “but is there any way to escape—or transform—this horrific dystopia,” Boyer answers by asking her own version of this innocent question:

“Also, how is capital not an infinite laboratory called “conditions? And where is the edge of the electrified grid?”

If that final question reminds you of The Truman Show, or the century long study of social engineering in the US (and UK), The Century Of The Self, you may not take it as merely a rhetorical, fatalistic, question. But in order to do this, you may also cross over the edge of what’s called “art” and elevate the ethical over the aesthetic that abstracts itself from it. “Some of us write because there are problems to be solved.” (3). She writes it so casually, but in many art contexts it’s defiant, even revolutionary, if its implications were taken seriously.

She troubles every frame she can find: “I think of all these things conferring authority and exclude them one by one, an experiment in erasing importance.” Yet Boyer is aware that there are those who need the assurance of convention, and tries not to speak down to them: “I’m an ordinary human who likes objects, too” as she theatrically tries on the conventions of self-help books and memoir with their bourgeois notions of individual happiness.

Yet Boyer excels when she grounds her vision in the class struggle, as Garments Against Women looks at this bourgeois world from the eyes of solitary, proletarian excluded from it (but also as someone battling with life-threatening cancer): “There are many things I do not like to read, mostly accounts of the lives of the free…” and “the constrainingly unconstrained literature of Capital produced aimlessness, alienation and boredom in me when I tried to read it.” Throughout the book’s first section, she exposes how this literature of Capital manifests itself through the non-professional, but at least as alienating, social media of the early 21st century:

“In the comment boxes of a popular fashion blog someone suggested any documentation of individual expression is in fact anti-social rather than pro-social, in that it is a record of individuation from the human mass.” (14)

This is, of course, a charming account of a wild party that brings people together! But how different is it from “people picking through the trash for their food.” Boyer doesn’t mean it merely as a metaphor—as she shows the social paralysis created by the people who brought you both instagram and the wealth gap:

“Taste is a weapon of class. Those guys have gotten together and agreed on their discourse: it will make them seem middling, casual like a sweater.” (14)

She diagnosis the problem and instructs, but does this offer escape? As the sequence winds to its end, she returns to the innocent questions that occasioned it: “Who dips in and out of it? What does it mean to give stuff up?”

Perhaps now she can start—to be “against information” (17) as well as against bourgeois art (even if one has to get tangled—or seem to get tangled—in its language to do so) and, last but not least, the culture created by the internet (which makes bourgeois poetry, for all its limits, seem potentially revolutionary by comparison): “We’re good—cheering content providers, boring despots—with a notebook in which to record the history of our stockpile of foods” (17)–and second hand, trash-picked foods at that.

In “No World But The World,” she turns her attention more thoroughly to the politics of the literary world, the insistent search for legitimacy as “poet” is another contemporary malady she diagnosis. How the aestheticization of poetry—especially heightened in the late 20th century’s “free verse” era has led to a culture—in America at least– in which:

The syntactical evidence of poetry without the frame of poetry is a crime that is much more criminal. Or, rather if it is not in the frame of poetry, poetic syntax is evidence, mostly, of having no sense. (18)

And in which poetry has become “the wrong art for people who love justice.” (19)

After this bold statement, she adds that poetry “was not like dance music.” This implies that dance music, almost categorically, loves justice more than what is called “poetry” today, but in a culture of free-verse literary or academic snobs for whom the fact that dance music has done more to bring people and communities together than even the most thoughtful, seemingly moral poetry, is of course “inadmissible evidence.” But Boyer, to her credit, sees through the ruse of that frame: “My favorite arts are the ones that can make you move your body or make a new world.” (19). Although you could say that in many ways her own writing is the opposite of dance music, its solidarity with that “non-poetic” form comes through clearest when expressed in the conventions of idea-driven prose syntax rather than “poetic syntax.”

This is a brilliant strategy that can unite the so-called “extremes” who have been divided (and conquered?) by an enemy that dresses up as moderation, as centrism, as middlemen’s rational golden mean (which can mean mean in both senses of the word)—as the choice between Democrats and Republicans, Coke and Pepsi or, in poetry, mainstream (say Helen Vendler) and experimental (say Marjorie Perloff); all the narrow choices that may suck us in as kids with their seeming breadth. And, by the way, I’d love to hear a performance of this sequence being read with otherwise instrumental dance music (old school R&B and funk, being my preference, but there could be several mixes)—especially the rhythmic list of “things” with which this sequence ends (page 20). With the right groove, it could become a track more popular than what’s called mainstream poetry without sacrificing any of its integrity.

Ultimately, Boyer hopes to change the ways we think about poetry, make it question its foundations, and reground itself at least as much as Blake, Laura (Riding) Jackson, or Amiri Baraka. If she can’t change the giant frame of the oligarchy, maybe her voice could at least have some say in changing the conversation that is literature. Is she can’t escape the cage, she can at least uncage her mouth!

***

In the long sequence, “Sewing,” the centerpiece to the book’s second section, she finds an alternative to the social media and high art of this consumer society that threatened to paralyze her (and us) in the book’s first section—to side with practical craft as a less alienated labor more analogous to dance music. As she points out how the invention of the sewing machine was threatening (and still is) to the captains of monopoly-capitalism:

“One of the inventors of the sewing machine didn’t patent it because of the way it would restructure labor. Another was almost killed by the mob”(29). Against this backdrop, it’s no mere fantasy to imagine oneself as the revolutionary Emma Goldman while sewing, even if capital has found a way to convince many to devalue this skill and buy overpriced garments made in sweat shops. Yet, if the first section of this book thinks globally, “Sewing” finds at least a foothold that can act locally. Even when she finds herself pressured by the needs of her daughter to by footwear, she is able to provide a heart-warming anecdote that can shield the young from the consumer “instincts” that social engineers from Alfred Bernays to Richard Berman (and the center for consumer freedom) have preyed on.

***

In Section three, “Not Writing” is a public list poem that calls attention to this refusal of the authority of any who wish to lock her up in poetry, or in memoir. The litany of negatives conjures a space away from commodified space to uncover the changing weather of creation. The follow-up piece “What is ‘Not Writing’” could be considered a manifesto against bourgeois notions of art as “play” rather than work, as she fleshes out her definition of work in more convincing ways than the proponents of the “free time” theory. If I’m ever able to start that “MFA In Non-Poetry” program (which would include everything currently called poetry, but yet be more capacious to include what Thomas Sayers Ellis calls “Perform-a-Forms”), I’d be more than honored to include this piece in its reading list.

With “Venge-Text” and “Twilight Revery,” the book takes on the tradition of the patriarchal love poem; as the speaker studies the dynamics of a romantic relationship with an intellectual, yet dissembling, control freak of a lover, she reminds herself. “This is just one available story. I have so far been able to construct 22.” This Petruchio-like male who fights for control on the level of language becomes representative of the “philosophical” male mode of the Euro-enlightenment tradition.

***

The 4th, and final, section consists mostly of a poor woman’s “memoir,” for those who distrust that genre and understand that memoirs are traditionally written by “property owners” (71). Yet, amidst all the horrors she recounts here of the inhumanity of the literary world, she manages to find some escape that may yet lead to genuine transformation:

I was poor, I was solitary, and I undertook to devote myself to literature in a community in which the interest in literature was, as yet, of the smallest. I believed that autodidacts were here to teach decency. I believed I’d lost my front.” (80)

I can absolutely relate to what she speaks here, as I see this in terms of my own shift to teaching foundational skills classes at a community college after teaching in an MFA program at a college with tuition so high it’s able to pay for—among other things—a million dollar bronze statue of the man who founded the school to help feed and educate poor people in “Let Them Eat Cake” France (he’d be rolling over in his grave if he knew).

As she accounts being rejected by, and or rejecting the conditional love of the literary world (the poetry “community”), she finds a kind of solace: “It appears she refused the ladder, but in truth she refused the rope.” To liberty, then, not banishment! Garments Against Women does speak the language MFA or Poetics sophisticates could appreciate, and perhaps this may yet help change the conversation, if not exactly “from within” at least close enough (as if she’s giving it one last chance to be real, even if she’s saying goodbye).

“Bon Pour Bruler” is a strong ending to anchor this collection, once again exposing the inhumanity of the European patriarchal voice as seen in Rousseau. Rousseau’s sexist account of why a young girl decided to stop writing brings us full circle, back to the quote from his contemporary, Mary Wollstonecraft, with which Boyer began her book. Like Wollstonecraft, Boyer refuses to be silent. By the end of this book, Boyer seems to have found a possibility beyond escape toward transformation in solidarity with a ragtag group of autodidacts, sewers and the “anti-literature” of catalogues, as she emerges as a woman who is able to use the various “garments” of her time (from “high-literature” to today’s “social media”) against themselves. - Chris Stroffolino

I tried to write an essay but failed. My essay failed because I couldn’t figure out how to weave the threads together in any wearable way. I kept getting stuck on something, especially at work: the edge of the cash register drawer, the lock on the rare books case. The essay that failed was mostly about the sticky substances suspended on the surface of social life, the kinds of feelings I’ve become obsessed with examining because of what they tell us about power relations: aimlessness, alienation, boredom, illness, depression, anxiety, shame.

These are the feelings Anne Boyer draws out in

Garments Against Women, a book of mostly lyric prose that pushes up against the boundaries of genre. “Her misery doesn’t require acts. Her misery requires conditions,” Anne writes in the opening pages, and even before she tells us, we already know: “How is capital not an infinite laboratory called ‘conditions’? And where is the end of the electrified grid?” It’s so ordinary it should be obvious, but this is the public secret Anne Boyer insists on talking about, what everybody knows but nobody admits.

Drifting through thrift stores and garage sales and shopping malls,

Garments Against Women registers the low-level alienation and depression that pervade the contemporary affective landscape. It’s the inconspicuous, the intimate, the quotidian forms of violence this book tracks relentlessly — the kind that demand the reproduction of life while simultaneously rendering life impossible. Shifting how we talk about the most common means of suffering,

Garments Against Women reconstitutes individual suffering as social. It’s a perspective that interrupts the numbness generated by a grueling system of exploitation by allowing us to see personal problems as structural.

In these small fragments of everyday life we get something between theory and memoir, between poetry and newsfeed. Moving between the analytical and aphoristic,

Garments Against Women gives us rigorous critique alongside wry humor, “The Animal Model of Inescapable Shock” alongside “

Ma Vie En Bling: A Memoir.” When Anne Boyer is not writing she is not writing

Leaving The Atocha Station by Anne Boyer, but she is also not writing a memoir because memoirs are for property owners: “I will leave no memoir, just a bitch’s

Maldoror.” There is trauma, which is the cause of so much not writing. There is spam from Versailles. Anne is at her sewing machine, like Emma Goldman, setting sleeves, waking up each morning to attempt a wearable garment. She is waking up with the desire to read everything. She is fastidiously taking notes.

A treatise on happiness which is actually a record of its opposite,

Garments Against Women is what confession looks like when language “prefers to live on the internet,” when “there is no such thing, really, as the public ever again.” The personal leaks into and out of the formal.

“There is a risk inherent in sliding all over the place. As if the language of poets is the language of property owners. As if the language of poets is not the language of machines,” but I keep sliding all over the place. My memory is shaky, my grasp of history uneven. I need to keep checking my notes. When Anne imagines writing a book called

A Woman Shopping (“If a woman has no purse, we will imagine one for her”) I think of Barbara Loden as Wanda, fumbling with her purse, drifting through rural Pennsylvania, leaving everything for nothing, or with the kind of desperation of a woman just trying to survive. A woman drifting through the street will still look like a woman shopping, though a flâneur is free of purses. “Why don’t you do something about your hair?” Mr. Dennis bullies Wanda, “It looks terrible.” So she goes shopping and buys a hat that looks more like a wedding veil.

What’s the difference between wide hope and desperation? I was trying to hold everything together, all at once. When I say my essay failed, I say it failed because I didn’t listen to my horoscope: “Feeling on the fence about something? Well, pick a side. You can’t be wish-washy.” I am wishy-washy, which means I want it both ways. I keep sliding all over the place, looking for better language.

There are at least two types of people in the world, Anne writes in the early pages

Garments Against Women: The first feels at home in the world, the second seems to be made of a different type of substance, one that repels the world at every moment. Do I really need to tell you which type of person I am? Wanda too, I imagine, is made of this second type of substance, which is maybe just a second kind of fortune.

The truth is I was sick, I was bedridden, I had no desire to get better. I did not want to talk about it, so I did not talk about it. Didn’t my exhaustion, my depression, my inability to walk down the stairs of my apartment and into the sunlight, point to all the ways capital exploits our inner reserves? I have been through enough schooling to know how to ask a smart question, but saying capitalism is the problem doesn’t help me get out of bed in the morning.

I mean I was sad and thought that was okay, even though I knew better than to let the difference between “I feel terrible” and “This feels terrible” become an immobilizing refrain. I was irresponsible, or maybe not. I read a lot. I sought intellectual refuge in the work of Sarah Ahemd, who has become a kind of patron saint of bad feelings. I saw myself as part of the tradition she delineates: the feminist killjoy, the unhappy queer, the angry black woman, the melancholy migrant. But “even heroic refusals often aren’t that heroic,”

Garments Against Women reminded me. I felt my sadness to be in me, deeply, at the same time as I understood it to be outside of me, generated by the world. There is no easy absorption.

It’s in recognizing this inability to cohere to the world — this inability or refusal to adapt to the conditions that make both life and literature nearly impossible — that

Garments Against Women is indispensible to my ability to actually believe in it. “After all,” writes Fanny Howe, “the point of art is to show that life is worth living by showing that it isn’t.” It’s at the precise moment of their impossibility, or failure, that both life and literature become possible again.

It’s Anne’s daughter who asks us to imagine what would happen if the world had no things in it — no cars, chairs, or cars. “People would make things,” she decides. “We would make things with trees and dirt,” which is another way of talking about the difference between being and doing, when surviving is, in and of itself, a form of accomplishment.

What do we need to survive? is one version of the question. “I feel like I read some, but still there are so many things of such importance about which I have never found a book,” is another. Reading helps, but communing with ghosts is deeply exhausting.

Garments Against Women may not offer us a way out, but it does enable a possible horizon. I mean: Things change. When the forms available to us — garments or literature — are not enough to fashion our survival, we need to find new ways of being alive. Rousseau’s little girl throws down her needle. “Everyone was very kind and wanted to help, but in order to be clear about it, I will tell the story like this: it appears that she refused the ladder, but in truth she refused the rope.” -

Anna Zalokostas Anne Boyer's Garments Against Women is a dress you've had for a long time that carries with it a life you remember well—it is the dress you are afraid of wearing again for all the burdens it housed during the time it was worn, for the history its manufacturing carries—it is the dress, it is no ordinary thing.

The book takes many shapes. At first it is an account, a diary, a kind of inventory for the speakers' happiness, her labor, her stress, her whim, and her peace.

It is both prose poem and pattern—

And then the book is also a garment, strips of fabric patterned with a language of searching, a language which is itself an accumulation of cloth.

A cloth which resists adornment and demands to have time taken with its seams, a kind of attention like "writing," like love and depression and sickness and motherhood.

These are some of the seams that attach the larger garment, Boyer's shame, with her culture—a culture I do not want to wear, a culture exposed in the poem "What is 'Not Writing'?" (and many others): "writing is like literature is like the world of monsters is the production of culture is I hate culture is the world of wealthy women and of men" (46).

One of the most compelling conflicts in the narrative is the speaker's shame of writing and her inclination toward sewing because "it is probably more meaningful to sew a dress than to write a poem" (29), as she writes in her poem "At Least Two Types of People."

Sewing becomes a kind of replacement for writing in which Boyer sees more value.

Boyer writes, "'writing steals from my life and gives me nothing but pain and worry and what I can't have' or 'writing steals from my already empty bank account' or 'writing gives me ideas I do not need or want' or 'writing is the manufacture of impossible desire" (29).

Writing generates blame for the speaker. It is a cause for her physical ailments: "When I was writing I had many symptoms including back spasms and ocular migraines, and then when I was not writing I spend one month feverish, infected in many places, weak, coughing, voiceless, allergic, itchy, with swollen joints, hands, and feet" (29). Here the speaker struggles to form a logic around the question of how one answers to pain.

There are moments in which I think of the garment as a kind of geography along whose landmarks we watch the speaker's world collect and unravel.

"There is no superiority in making things or in re-making things," (20) she writes in "No World but the World."

Writing for the speaker inhabits a false existence, it makes reality dreary by comparison—it is a burden, or a prison of sorts.

It is a privilege, but it is also ordinary.

I am not special.

Anne Boyer is not special.

She writes: "It's like everything else, old men who go fishing, hair extensions, nail art, individual false eyelashes" (20).

Boyer spans unusual possibilities which are oftentimes humorous, as the combinations are so surprising: "flowers that might even be marigold and petunias" and "perfume that smells like party girls…perfume that does not smell like flowers or more like flowers mixed with the urine of jungle animals and some tobacco smoke" (20). As the language here is "making things" or "re-making things," I begin to see these moments of raw imagery as monuments along a map.

These patterns are as otherworldly in their syntax as they are familiar in their bleakness: "the cracked dirty swimming pools of low-rent apartment complexes, bleach-haired boys smoking dope along a chain-linked fence" (20).

The speaker pulls from different parts of her memory to create a schema, a method for the reader to navigate her world as though sewing a garment.

Boyer is as much a cartographer as she is a seamstress and a poet.

But she is an activist more than any of these things.

Boyer's probing of Western culture is at the forefront of Garments, and her tone devotes itself to the lives that suffer to create a garment. It is a tone that does not to show itself off, it prefers to inform, to create details and categories.

And then the garment becomes a rupture in routine, a subversion of logic and language: "the stateless state of contract labor, the invisible IV also the invisible catheter, everyone hugging the duct tape replica like starving little rhesus monkeys,

everything in the everything like 'there is no world but the world!'"(20)—Which sounds like a subversion of something along the lines of that's just the way it is—a way to avoid addressing the problem.

We see the speaker's own poverty, "I make anywhere from 10 to 15 dollars an hour at any of my three jobs" (20) as she diagrams her guilt, "The fabric still contains the hours of the lives, those of the farmers and shepherds and chemists and factory workers and truckers and salespeople and the first purchases, the givers-away, who were probably women who sewed" (20).

The garment, in addition to everything else, is evidence.

The lives on the other side of the garment suffer, and you are wearing it as an ornament.

Accumulating more cloth, Boyer writes in her poem, "Sewing": "I sew and the historical of sewing becomes a feeling just as when I used to be a poet, when I used to write poetry, used to write poetry and that thing—culture—began tendrilling out in me" (29).

Writing becomes a term, "writing," which has its own context and rules for Boyer. It is most often understood in terms of its antithesis, a term Boyer calls "Not Writing."

In her poem "Not Writing," she states, "It is easy to imagine not writing, both accidentally and intentionally. It is easy because there have been years and months and days I have thought the way to live was not writing have known what writing consisted of and have thought 'I do not want to do that' and 'writing steals me from my loved ones'" (46).

Like writing, "not writing" produces a very specific pattern of problems and consequences: "I thought it was my writing that was making me sick," (6) she writes in "The Innocent Question."

Boyer continues, "when I was writing I had many symptoms including back spasms and ocular migraines, and then when I was not writing I spend one month feverish, infected in many places, weak, coughing, voiceless, allergic, itchy, with swollen joints, hands, and feet" (6).

Writing is against not writing; negations form the speaker's orientation.

A garment is understood as what it is "against."

Against the speaker, against women whose identities are informed by clothing in the eyes of the world, against women who are overworked in factories, against children who are forced into labor.

I found myself frequently returning to Anne Boyer's Garments Against Women during this slow summer. It was something that I believe I wore, that I am still wearing.

I pull some of the loose frays carefully—

I make sure to iron it—

it is a book I felt at home with.

It is a book that told me I am not important,

that Anne Boyer is not important—

it is a book I want to preserve, to take care of. - Isabel Balée

It was in September I totally fucked with chronology. I thought memoirs were written by property owners. I was about to fall in love with younger men. When I went back to work at my former employer, offices had been established inside of elevators, and I was asked by my boss “Well do you want to go to the dinner because that would make it 102? Too many, don’t you think?” His daughter was dressed as a witch. I taught her to say Maximus.

In auditoriums, cheerleaders practiced their dances, different squads in different colors with different choreography dancing to the same song. Outside, climate change had caused the environment to become a disaster movie called “Ice Age.” This meant if you stepped off the veranda you would be engulfed by an icy, hard-driving flood, and there would be a soundtrack and voiceover for this. (“Ma Vie en Bling: A Memoir”)

I’ve been struck by Kansas poet and visual artist Anne Boyer’s remarkable collection of prose poems, Garments Against Women (Boise ID: Ahsahta Press, 2015). Her second full-length poetry collection, Garments Against Women follows The Romance of Happy Workers (Coffee House Press, 2008) and numerous chapbooks, including Anne Boyer’s Good Apocalypse (Effing Press, 2006), Selected Dreams with a Note on Phrenology (dusie, 2007), The 2000s (2009), My Common Heart (2011) and A Form of Sabotage (2013), as well as a book of conceptual work, Art is War (Mitzvah, Lawrence, 2008). Organized in four groupings, each containing a small handful of poems, the pieces in Garments Against Women are incredibly compact, and move through a series and sequence of thoughtfully compact and restless meditations on boredom, philosophy, sewing, reading and innocence (real and otherwise): “What is the difference between happiness and pornography? I mean what is the difference between literature and photography?” she writes, as part of the extended sequence “The Innocent Question.” There are repeated references within the collection of a writer who isn’t writing, whether through choice or circumstance: “Having given up literature, it was easy to become fixed on the idea of a single shirt, one with two pieces, no facings, not even set in sleeves.” (“Sewing”). When I originally read her “Not Writing,” I had presumed I was reading the work of an older, and far more established writer; suggesting a wisdom gained through hard-won experience, resulting even in a bit of wear. As the poem opens: When I am not writing I am not writing a novel called 1994 about a young woman in an office park in a provincial town who has a job cutting and pasting time. I am not writing a novel called Nero about the world’s richest art star in space. I am not writing a book called Kansas City Spleen. I am not writing a sequel to Kansas City Spleen called Bitch’s Maldoror. I am not writing a book of political philosophy called Questions for Poets. I am not writing a scandalous memoir. I am not writing a pathetic memoir. I am not writing a memoir about poetry or love. I am not writing a memoir about poverty, debt collection, or bankruptcy. I am not writing about family court. I am not writing a memoir because memoirs are for property owners and not writing a memoir about prohibition of memoirs.

When I am not writing a memoir I am also not writing any kind of poetry, not prose poems contemporary or otherwise, not poems made of fragments, not tightened and compressed poems, not loosened and conversational poems, not conceptual poems, not virtuosic poems employing many different types of euphonious devices, not poems with epiphanies and not poems without, not documentary poems about recent political moments, not poems heavy with allusions to critical theory and popular song.

Some of this wear can even be seen in her 2006 interview with Kate Greenstreet: “I stopped writing poetry for years. / I expected nothing from poetry. / I wrote expecting nothing. / I tried for nothing. I wrote a book. / I still expected nothing.” What is it that wears her down, and what is it that continually brings her back around? - Rob McLennan

In the first pages of his Confessions, Jean-Jacques Rousseau recounts the death of his mother during childbirth, concluding melodramatically: “So my birth was the first of my misfortunes.” Maternal death, not uncommon in Rousseau’s time (and, appallingly, to this day), is, perhaps, a stark metonym for the dark side of reproductive labor; its full spectrum forms a constitutive thread—alongside illness, information, happiness, pornography-as-literature, and the broader relation of persons to Capital (“an infinite laboratory called ‘conditions’”)—of Anne Boyer’s Garments Against Women. The book of (mostly) prose, divided into unnamed sections and dedicated to Boyer’s daughter, bears an epigraph from Maria: or the Wrongs of Woman, in which Rousseau’s contemporary Mary Wollstonecraft details her protagonist Maria’s reasoning for writing about the events of her past: “They might perhaps instruct her daughter, and shield her from the misery, the tyranny, her mother knew not how to avoid.” The distinction between these two impulses toward autobiography—one that recasts the trauma of others into a personal misfortune, and one that makes of personal trauma an heirloom weaponized against injustice—may be the distinction between conventional (even brilliant, even political) memoir and Boyer’s achievement in Garments, in that the former is concerned with the question How did I become who I am today?, the latter with the question Why am I not not writing? The double negative isn’t decorative; it mimics forms of desire and of politics that run throughout the book: Not writing is working, and when not working at paid work working at unpaid work like caring for others, and when not at unpaid work like caring, caring also for a human body, and when not caring for a human body many hours, weeks, years, and other measures of time spent caring for the mind in a way like reading or learning and when not reading and learning also making things (like garments, food, plants, artworks, decorative items) and when not reading and learning and working and making and carrying and worrying also politics, and when not politics also the kind of medication which is consumption, of sex mostly or drunkenness, cigarettes, drugs, passionate love affairs, cultural products, the internet also, then time spent staring into space that is not a screen, also all the time spent driving, particularly here where it is very long to get anywhere, and then to work and back, to take her to school and back, too. Desire both for and against writing, both for and against desire: “There is envy which is also mixed with repulsion at those who do not have a long list of not writing to do.” Given that we are reading the result of it, what, or whom, is this not-not writing for? That question—of literature and the literary—troubles the whole of this book, not in the psychological sense of being troubled (there is embarrassment, shame, fury and worry here, but the energy isn’t that of anxiety) but in the sense of “she’s trouble.” It can be approached through humor, as when, of a Pulitzer Prize winning novelist who “believed that the mind had two places, the conscious and subconscious, and that literature could only come out of the subconscious mind, but that language preferred to live in the conscious one” Boyer concludes “This is wrong. Language prefers to live on the Internet.” But the question is addressed most explicitly (though not transparently—no names are named) in “Ma Vie en Bling: A Memoir,” in which Boyer recounts moving through a particular moment in the (poetry) world as a woman who in addition to “devoting [herself] to literature” also took men as lovers, and whom men threatened publicly and privately to destroy while others insisted the blue sky she has seen is not actually blue. It was a moment in which “people wrote on machines that connected to machines that connected to machines that connected to people who wrote on machines” and when “we believed in information.” But, Boyer writes, “I did not believe in information. I liked to imagine the interfaces that would make the public private and make the private okay.” Garments Against Women is such an interface, updated for a more fractured moment where “we can barely remember what once formed us, and the last and first thing any of us thinks about is poetry.” One of the most laborious and necessary forms of care may be not to make things okay, but to make making things okay, whether the shameful (because hidden) sloppy seams of a home-sewn skirt or the stark formulations of a child. It has something to do with not not writing and with the way Boyer interrupts the roman-a-clèf trajectory of “Ma Vie en Bling” to give us this scene:

Around that time my daughter and I had this exchange:

Anne, imagine if the world had nothing in it.

Do you mean nothing at all—just darkness—or a world without objects?

I mean a world without things: no houses, chairs, or cars. A world with only people and trees and dirt.

What do you think would happen?

People would make things. We would make things with trees and dirt.

—Anna Moschovakis

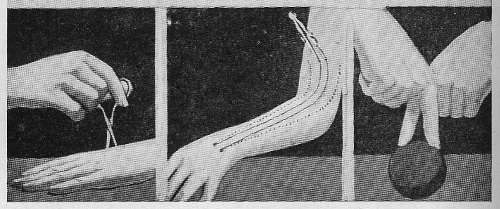

Image: Loomshuttles / Warpaths, Ines Doujak, 2013

Madame Tlank digresses from and back to Anne Boyer’s Garments Against Women, which is many things. A memoir written by someone without a history. A garment made for no-body. A reproduction fin in a great fleet of sharksDown With Supreme Whateverness: On Anne Boyer's Garments Against Womena catalogue of whales that is a catalogue

of whale bones inside a catalogue of garments

against women that could never be a novel itself.

‘Who eats in a cage? Or with a caged mouth?’ This question leaps in white out of the first two black pages of Anne Boyer’s

Garments Against Women. In it, the need to eat is shouted out loud. In it, the cage is seen and felt. And it’s made clear that in order ‘to survive survival’, to eat without a cage, it’s not enough to shift the cage (from mouth to just around the body, say): it needs to be ripped away. And fangs regrown.

Kafka’s

Hungerkünstler refused the terms of survival that were laid out for him: he put himself deliberately into a cage, on public display, and refused to eat; the worst for him was to be force-fed once every 40 days; the sheer effort of lifting himself up to have food poured down his throat was already too much, so little interest did he have in survival. And why? Because, as the Hunger Artist confesses just before he perishes, ‘I could not find a food that tasted good to me.’ Because he could see no point in surviving survival. It was all just so much pale grub.

![]()

In Boyer’s writing, of course, the cage is no protection from present conditions, it

is the present conditions, as embodied for example in garments and literature: ‘Literature, like garments, had so often been against so many of us, enforcing and sustaining the hostilities of a world with the unequal distribution of resources and the corresponding unequal distribution of suffering.’ Survival itself requires assenting to those conditions, eating at least, if with a caged mouth. Refusing this survival means not-writing: not (in writing) (re)producing the conditions that would call such survival ‘life’. But accepting this survival

also requires not-writing: paid and unpaid work, reproduction, etc. – things necessary for survival produce not-writing too. So that surviving survival, the will to want to live, to write, requires a world turned inside-out. And in

Garments Against Women Boyer attempts to ‘imagine, foreshadow, call forth or negatively invoke a [writing] incommensurable with Things As They Are.’ (MH) It is a labour of love & rage.

But who would publish this book and who, also, would shop for it? And how could it be literature if it is not coyly against literature but sincerely against it, as it is also against ourselves?(p.48)

One version of Things As They Are:

If an animal is inescapably shocked once, then the second time that she is shocked she is dragged across the electrified grid to some non-shocking space, she will be happier than if she isn’t dragged across the electrified grid. The next time she is shocked, she will be happier because she will know there is a place that isn’t an electrified grid. […] She will go to the shocking condition – ‘science’ – and there in this condition she will flood with endogenous opioids, along with cortisol and other arousing inner substances. […] how is Capital not an infinite laboratory called ‘conditions’? And where is the edge of the electrified grid? (pp.1-2)

Boyer tests these conditions, putting their accidents on the page because others will have to go on doing so. She probes and tests, flinching, letting go and pushing on, up and downward. Made sick by ‘the supreme whateverness of upward moving depths’(p.53) – by the ‘unconstrained constraints’ (p.12), the bullshit choice between happiness or infirmity – she senses what lies between the pages of the closed book (‘another veracity that includes conspiracy, corners, shadows, slantwise, evasion, unsayingness, negation, and under-the-beds?’(p.36)) With her mind as the deadpan-logical mouse in this laboratory, Boyer tries to invert and hollow out the conditions, to lift the real from its carefully constructed frame.

![]()

Among components of the frame are:

1. The violence underlying everything, or ‘how money and bodies meet’ (p.9).

2. The need to make money (and to ‘

Be MONEY

like the universe!’)*. Transparent accounts and profitable desires.** The aspiring self itself and its cheaply bought mutations***.

*‘Be MONEY’ (p.69): in a hilarious half-page of the section called ‘Ma Vie en Bling: A Memoir’, Boyer corrects bits of high-serious canonical bluster (Char, Pasternak, Pessoa, Auden) by replacing the words ‘poetry’, ‘art’, ‘plural’, ‘inspiration’ with ‘MONEY’. In the line quoted above, Pessoa originally cried out: ‘Be plural […]!’ Auden, who thought he was talking about ‘inspiration’, is discovered by the same method to have said: ‘Such an act of judgement, distinguishing between Chance and Providence, deserves, surely, to be called MONEY’. Do try this at home.

**‘Profitable desires’ (pp. 34/35): ‘It’s only necessary to make a transparent account if it’s necessary to have accounting, and it’s only necessary to have accounting in the service of a profitable outcome. To account in the service of profit is to assume the desirability of profit […] To steal is to behave as a natural extension and reinforcement of a desire that everyone knows is what’s real.’

***Cheaply bought mutations: ‘as if the smallest bit of drugstore blonde could alter a person’s person’ (p.6). ‘On how many of my hours are gone now because I have had to shop / On how I wish I could shop for hours instead’ (p.47) – for hours or for hours? ‘On whether it is better to want nothing or steal everything’ (p.47).

3. The body: the need to eat, the (impersonal) illness resulting from poverty*

, infirmity**, our wants ‘made out of what is done to us’, the subsistence that goes on after power defangs us.

*‘Poverty’: ‘I was too sad to slug in the face. I was stoned and inconsolable. I was a weary rocket engineer looking at the twisted remains of a bad shot-defined astronautics. I wanted to be addendum free’. (p.63)

**‘Infirmity’: ‘I am not a fan of infirmity, though it does supply the opportunity for some relief.’ (p.13)

Fangs – we need them!

Literary convention established to make knowing what we needed to impossible

By continuing to write after having failed to refuse to write, by writing, Boyer wills literature to stop (re)producing these conditions, stop functioning within or creating a frame (as do garments, encasing bodies which might flail their arms uncontrollably) that disguises the violence on which it is built.

![]()

Just one example of Boyer’s expert frame-shifting: ‘

The classic example of a positive contrast is produced by hitting yourself on the head with a hammer. The pain produced is part of the ordered dimension and so the more of it the more you get adapted to. Thus, when you stop you “feel great”.’ (p.14). And, later in the book: ‘Things were great after that. They really got better. I wrote words in great paragraphs. There were great acorns. I had a great toothache. There was the great noise of the great leaving geese.’ (p.70).

An impulse to action sings of a semblance [...] The measure [...] congealed [...] things keep no resemblance [...] Like night is like us [...] mentors [...] hardly enter [...] our centers do not [...] our value estranges.

– LZ

Writing (or its product, literature) needs to be wrenched from its place in the given conditions (as literature

against women, just as sewing must know its material, re-grounding the garment as use value (as opposed to a form wrenched out of and imposed on women). And: how to make a seam?

Poetry and clothes are made of the same stuff: the history contained in the fabric or language; the hours of labour embodied in that material and its transformation into garment or poetry. The history of those who wrote and sewed the stuff: the present tense of those who read and wore it, those who heard and saw them. Dead labour walking whenever you wear that dress. Each time you recite that poem to protect you in the violent rain you bring forth the zombies.

Writing needs to expose its threads, garments need to bring back their dead bodie

s.

I kept checking the social fabric for the hole I'd burned. (p.80)

Uprooting the history of the Now entails ‘resistance to the present and its versions of the past’ (MH). Elsewhere, in a sequence of ‘Questions for Poets’ published by

Mute, Boyer asks, ‘What is the direct trial that is today? This text is not only a catalogue of questions, it is also a bibliography of the writing that gave rise to the questions, and as such a history of questions. The first reference in the first of many footnotes rings out: ‘The direct trial of him who would be the greatest poet is today.’(WW).

Poetry is history writing, a history of and in the now, ‘everything in the everything’ (p.20). And then, after many questions Brecht could not have asked better, comes this: ‘Is it all of that and how it is against ourselves? Is it to burst, to ruin / to disrupt our continuity with history? Is it to never have history again? Is it the enclosing of tears?’

![]()

A poem is (or can be) a split second, a century, re-written as condensed NOW; a quake in continuity. Can it work into a present-tense nervous system the ‘actual heaving everything of the human everyone’ (p.51)?

I shall be a charming, utterly spherical zero.

– RW

Maybe the little girl’s 0s (as described by Rousseau in

Emile, the only thing this girl would write and write and write)

, shaped backward, using a needle, constitute writing towards surviving survival.

Boyer lists some things the girl might have enclosed into her 0s, ‘a planet, a ring, a word, a query, a grammar’(p.84). Or maybe the 0 was just a NO: endless repetition of a symbol devoid of meaning without a context. Refusing to signify. And drawn backward at that. With a needle (not making garments), not a pen (not writing language). The possible worlds contained in the negation. Rousseau claims the girl stopped writing because she saw herself writing and hated what she looked like (but maybe she just thought that her 0s were too beautiful for this world?). ‘Afterwards’, he writes, ‘she was only persuaded to write again in order to mark what was hers.’ The refusal failed, the girl adapts but

not quite. She never wrote again, only

marked what was hers. Her territory. Objects delineate her world. But Boyer sees it otherwise: the girl stops because she is done with her work: ‘The little girl in Rousseau needed only to write down her own name now: she had written, already, her revolutionary letters in the code of 0’s.’(p.85) Revolutionary letters, decoded in Rousseau’s head: an impulse stalled. In Boyer’s writing: an impulse continued – – – – –

Negative alphabets.

I am nothing and I should be everything.– KM

-

Madame Tlank The Virus Reader

I offered his virus to the mechanized virus reader. It had many functions, among these the one that translated “virus” into “sick room architectures.” Thus the design specs for his recovery: a 15 × 15 outdoor room with a perimeter of medium-height pines, inside of these pines a hospital bed and an eight-foot flat-screen T V.

“at first it appeared that she was weeping so that I might change my mind and buy the $44 shoes, but soon she was unable to stop weeping. she refused to try on other shoes in other stores even though the shoes she wore were too small and had recently been in a mud puddle. she could see how even not-the-best-shoes-ever not-the-shoes-that-looked-like-art would be better than dirty ill-fitting shoes, but she could not stop weeping. we walked through stores while she wept. we sat in the middle of the mall while she wept. we went to a discount store, and I told her I would just pick out shoes for her because she wept too much to try on shoes. she wept in the discount store. she wasn’t weeping by design. she couldn’t stop weeping, then she stopped weeping a little and we found some brown sneakers for $44 on clearance. in the car I wanted to weep, too, but she said to me ‘I am still a child and am learning to control my impulses and emotions. you have had many years of dreams and realities to learn from so there is no excuse for you to cry.’ she paused. ‘do you have enough dreams?’ she finally asked.”

The Animal Model of Inescapable ShockIf an animal has previously suffered escapable shock, and then she suffers inescapable shock, she will be happier than if she has previously not suffered escapable shock — for if she hasn’t, she will only know about being shocked inescapably.

But if she has been inescapably shocked before, and she is put in the conditions where she was inescapably shocked before, she will behave as if being shocked, mostly. Her misery doesn’t require acts. Her misery requires conditions.

If an animal is inescapably shocked once, and then the second time she is dragged across the electrified grid to some non-shocking space, she will be happier than if she isn’t dragged across the electrified grid. The next time she is shocked, she will be happier because she will know there is a place that isn’t an electrified grid. She will be happier because rather than just being dragged onto an electrified grid by a human who then hurts her, the human can then drag her off of it.

If an animal is shocked, escapably or inescapably, she will manifest deep reactions of attachment for whoever has shocked her. If she has manifested deep reactions of attachment for whoever has shocked her, she will manifest deeper reactions of attachment for whoever has shocked her and then dragged her off the electrified grid. Perhaps she will develop deep feelings of attachment for electrified grids. Perhaps she will develop deep feelings of attachment for what is not the electrified grid. Perhaps she will develop deep feelings of attachment for dragging. She may also develop deep feelings of attachment for science, laboratories, experimentation, electricity, and informative forms of torture.

If an animal is shocked, she will manufacture an analgesic response. These will be incredible levels of endogenous opioids. This will be better than anything. Then later, there will be no opioids, and she will go back to the human who has shocked her looking for more opioids. She will go to the shocking condition — called “science” — and there in the condition she will flood with endogenous opioids, along with cortisol and other things which feel arousing.

Eventually all arousal will feel like shock. She will not be steady, though, in her self-supply of analgesic. She will not always be able to dwell in science, as much as she now believes she loves it.

That humans are animals means it is possible that the animal model of inescapable shock explains why humans go to movies, lovers stay with those who don’t love them, the poor serve the rich, the soldiers continue to fight, and other confused, arousing things. Also, how is capitalism not an infinite laboratory called “conditions”? And where is the edge of the electrified grid?

At Least Two Types of People

There are at least two types of people, the first for whom the ordinary

worldliness is easy. The regular social routines and material cares are

nothing too external to them and easily absorbed. They are not alien from

the creation and maintenance of the world, and the world does not treat

them as alien. And also, from them, the efforts toward the world, and to

them, the fulfillment of the world's moderate desires, flow. They are ef-

fortless at eating, moving, arranging their arms as they sit or stand, being

hired, being paid, cleaning up, spending, playing, mating. They are in an

ease and comfort. The world is for the world and for them.

Then there are those over whom the events and opportunities of the every-

day world wash over. There is rarely, in this second type, any easy kind

of absorption. There is only a visible evidence of having been made of a

different substance, one that repels. Also, from them, it is almost impos-

sible to give to the world what it will welcome or reward. For how does

this second type hold their arms? Across their chest? Behind their back?

And how do they find food to eat and then prepare this food? And how

do they receive a check or endorse it? And what also of the difficulties of

love or being loved, its expansiveness, the way it is used for markets and

indentured moods?

And what is this second substance? And how does it come to have as one

of its qualities the resistance of the world as it is? And also, what is the

person made of the second substance? Is this a human or more or less

than one? Where is the true impermeable community of the second human

whose arms do not easily arrange themselves and for whom the salaries

and weddings and garages do not come?

These are, perhaps, not two sorts of persons, but two kinds of fortune. The

first is soft and regular. The second is a baffled kind, and magnetic only to

the second substance, and made itself out of a different, second, substance,

and having, at its end, a second, and almost blank-faced, reward.

‘Literature is against us': In Conversation with Anne BoyerIf you don’t know

Anne Boyer’s work, you should. She’s a fierce intellect, tremendous poet, and laudable person. I’m grateful she spent time untangling my meandering questions. Her new book,

Garments Against Women, is just out from Ahsahta Press, a perfect fit for Boyer’s words. We talk politics, protest, the personal and poetry. Boyer’s strength and insights make me hopeful, and that is worth everything.

![Portrait with Mel Chin’s “revised post soviet tools to be used against the unslakable thirst of 21st century capitalism”]()

Portrait with Mel Chin’s “revised post soviet tools to be used against the unslakable thirst of 21st century capitalism”

Hi Anne Boyer—I’m reading

Garments Against Women, your latest that has been described by Chris Stroffolino as “widening the boundaries of poetry and memoir” (

The Rumpus). It is for me something of a memoir of the mind in real time. That is, the persona (you?) explores the things she is considering, weighing, analyzing, on the page. This resonates with the ways in which social media posts so often deal with the social and current happenings, except in this case,

Garments isn’t so much responsive to current events but perhaps to what the persona is thinking through, the ideas of social order she is interrogating, how a person navigates many mediums, etc. Do you think the ways in which we interact through social media influenced your approach? (Have the mechanisms and conditionings of social media affected your writing for the page?)

Anne Boyer: Hi Amy King—Thank you for taking the time to read my book and to ask me questions about it. When you say “a memoir of the mind in real time” I think you must be a very astute reader: that’s most likely the way any book would come out if anyone was reading what I was reading at the time I wrote it, I think.

The scene of the book then is a scene of the struggle to be a person who could think and write, the account of a person who isn’t supposed to be spending much time in intellectual activity yet does despite, even if she thinks it makes her sick, even if she has to do in the negative, even if the only territory in which to think is that of the terrifying and too-generally-articulated

not-.Aaron Kunin had recommended I read Jean Jacques Rousseau and Hannah Arendt, so I went to the library and checked some stuff out, and everything followed from there. Rousseau met me at the problems of confession, of gender, of “freedom,” and Arendt at the problem of appearances, of the object world, of reason and of will, of the question of survival itself as the grounds for freedom. Arendt, though, never answers what we are supposed to do when anything beyond survival is scarce. Rousseau can’t answer much of anything, only seduce and mislead and really hurt our feelings, writing such terrible things about us (women and girls). Neither of them were writing for a reader like me, at least as I was living at that time.

And yeah, social media lends certain structures the thoughts and feelings of everyone who uses it, but much of this book was written during periods of refusal—refusal of the blogs, times I’d turn off the internet, refusal of poetry’s available socialities and structures. I wanted to figure out some way to live as something more than information. I wanted to figure out some way to write what we need that wasn’t going to turn it into a pornography of particularization. That we are alienated, that we are unsure, that our next month is so regularly worse than our this one, are things common to many of us, are these hard and ordinary things of life as it is now which an algorithmic display of affect can’t soften. The feeds could weep all day long, and it wouldn’t mean they won’t also be crying harder tomorrow. So what are we supposed to do?

Amy: “…even if the only territory in which to think is that of the terrifying and too-generally-articulated

not-” Is this writing, even if it is making you sick, happening around the time you were diagnosed with breast cancer? Is the articulated not- heightened by this experience? Or are you referring to the less specific but common human condition of being aware of our mortality, our inevitable nothingness, and how writing, with all of its promise of immortality, cannot redeem this inevitability that already exists?

Anne: This book was written a while ago, mostly in 2010 and some years before. My daughter and I were struggling, then, in the kind of poverty in which you are always getting sick from stress and overwork and shitty food then having no insurance or money or time to treat the problems caused by having no insurance or money or time. I began to believe that it was the extra burden I put on myself to be a writer that was making me sick and that we would be a lot happier and healthier if I could give it up. Things changed for us in 2011, fortunately, and as soon as I got a full-time job with health insurance and enough income to cover the rent, I stopped getting sick until I was diagnosed with breast cancer in September of 2014. The “not” in the book, then, is quite general. The “not” I learned about last year is a whole other story.

Amy: My partner,

Melissa Studdard, is also a single mom, rarely gets sleep, takes on extra work and gets sick regularly from overworking and pushing herself to write. Can you talk a little bit about what it means to be a woman in this country, raising a child single-handedly, often with little to no financial help from the other parent, and the impact of that on you as a writer? Has that situation—and the relief from the full time job–directly impacted your writing in terms of content or even simply productivity?

Anne: I didn’t know how to do it. I still don’t. My daughter is fifteen now—that means I am very close to having “done it”—that is, “raised her”—and I still don’t know how anyone does. I was desperate for models of how to be a single mother and still get a chance to write, to have an intellectual and creative life, how to do it without it bringing real harm to one’s child or children. The search for models led me to some of my favorite poets, people like

Alice Notley and