My Shadow Book by Maawaam, ed. by Jordan A. Rothacker, Spaceboy Books, 2017.

excerpt

www.jordanrothacker.com/

Percy Shelley once remarked, “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.”

What if Shelley was right, but his understanding didn’t go far enough? What if there was an ancient, interdimensional, supernatural cabal that strives to direct human progress, that has worked tirelessly in the darkness to save our world in spite of our enlightened penchant for destruction? Novelist and literary scholar Jordan A. Rothacker shares his discovery of the notebooks of Maawaam, a Shadow Man and member of the secret society of Shadow Men and Women. What does Rothacker’s discovery mean for our world? Will Maawaam’s cryptic fragments, like the Rosetta Stone, provide a key to understanding this ancient and powerful tradition?

Science fiction or memoir; poetry or prose; art manifesto or political call to action; wisdom or nonsense? What is Maawaam’s Shadow Book but what lies between, what lies in the shadows. – from the Spaceboy Books website

“My Shadow Book contains multitudes. It’s a fascinating collage of quotations, diaries, drawings, aphorisms, confessions, short fictions, and political manifestos. Concealed within is a clever Mobius strip narrative and an invitation to a secret society comprised of history’s most subversive artists. It’s many potential books in one, waiting only for a reader to bring it to life.” – Jeff Jackson

“Jordan Rothacker’s ebullient, entrancing, playful, linguistically sensuous My Shadow Book is a triumph of narrative and structural inventiveness. As the intrigues and mysteries unfold, Rothacker’s polyphonic storytelling becomes a journey of ever-increasing entrancement. Invoking the epic speculative works of Clarice Lispector, Milorad Pavic, Edmond Jabés, and Borges, My Shadow Book is a masterfully crafted kaleidoscopic reinvention of literary beauty: a fragmented, arcane, haunting, and deliciously luxurious complexity of shimmering light that illuminates the very edges of thought and language.” – Quintan Ana Wikswo

In the summer of 2011, novelist and scholar Jordan A. Rothacker discovered a box containing the journals of a being known as Maawaam. Thus begins My Shadow Book—part literary manifesto, part metafictional frame narrative. The novel itself is credited to Maawaam, while Rothacker gives himself the title of editor. This framing device, the found manuscript, is used throughout literature as a way of creating verisimilitude in the reading experience. By claiming to have found and compiled Maawaam’s papers, Rothacker gives the novel legitimacy as a real, authentic document, while also absolving himself of any blame for the contents: he simply discovered these writings, and so is not responsible for their creation.

Despite Rothacker’s apparent effort to distance himself from the fiction, in Maawaam we have the character of a struggling writer. He calls himself a Shadow Man, a “double agent” writing in the darkness while presenting himself as a functioning member of society in the light. Is “Shadow Man” another way of saying “artist,” or is Maawaam otherworldly? Perhaps both. In his journals, Maawaam quotes William S. Burroughs, Anna Kavan, and Guy Debord; he writes about his love life and his deepest anxieties; and he includes excerpts of stories, poems, and novels he’s trying to write. He is deeply human. And yet all of this takes place in the shadows, where he convenes with other Shadow Men and Women. Maawaam refers to regular people as “the people of the sun.” He fragments his journals with a series of black stars, both to indicate section breaks and to remind readers that he lives by the light of a different, darker sun.

As in his previous novel And Wind Will Wash Away, Rothacker here displays his wisdom, subversive influences, and literary prowess. He crafts a character better read than most of us, but also greatly troubled by his own psyche. Maawaam’s ruminations read like a love letter to suffering artists everywhere:

There are those nights when you get up to go to the bathroom—she remains there asleep—and you catch your reflection and you can see he is dying and you feel like you’re dying and you can feel it, the dying slowly and you wonder, is this how everyone feels all the time?

That question—is this how everyone feels all the time?—is fundamental to why we read. Literature gives us the opportunity to glimpse other lives and understand how other people think and feel, and the more we read, the more we realize that our feelings can be found reproduced in countless others.

Maawaam is obsessed with the phrase “give up the ghost,” which he interprets as a Shadow Man giving everything to the people of the sun. This sounds like both an unburdening of the soul and also a form of death. He says: “I have tried in my own way to be free… I have tried in my own way to give up the ghost. So many ghosts to give up before the final ghost.” These ghosts are the innumerable lives he’s created in the shadows, through fiction and poetry. For Maawaam to give up the ghost he must share his work with the world—a monumental task requiring him to finish the stories, poems, and novels he’s begun, or show them to us in their rough, unfinished state.

In The Secret Name, one of the novels Maawaam is writing, the protagonist (named Landry Bread) is sent on a journey to discover his “secret name.” Landry is a hopeless guy living in Atlanta, and wants nothing more than to believe there’s something more to him, some secret other self waiting to be discovered. Instead, what Bread finds is a novel titled Amerika the Beautifuk by a mysterious and enigmatic author named Maawaam (a book within a book within a book). Here we have the character, Maawaam, discovering his own secret name inside the text he’s writing:

in finding that name, and writing that character, I was writing a role for myself. I could write the novel, The Secret Name, and I could stage it like I found it, a manuscript in a box somewhere, and I am just the editor of it, and the actual author is this MAAWAAM. He is the author of the inner and outer text. The story of Landry Bread just floats there in the middle.

The writer is essentially and irremediably tied to his work. Attempts to detach from the writing—through pseudonyms, frame narratives, and invented worlds—invariably lead the writer back to himself and his own anxieties and obsessions. But there is also pleasure in inhabiting this invented world. Maawaam’s mind is labyrinthine, and while it may contain some fictionalized elements of its creator, it is unique and compelling, and worthy of being explored in the closeness My Shadow Book achieves.Rothacker’s novel, disguised as a journal containing a novel (and so on), is at times dizzying. The form is challenging in its unyielding metafictional twists. Identities are nested one within the other. What makes the novel so impressive is how, through all of these experiments in storytelling, Maawaam’s vulnerability and desire are thoughtfully articulated and reiterated in various aphorisms, quotations, and poems, in a feedback loop of loneliness and longing.

This is a strange and ambitious novel. To invent a writer whose work is as bizarre as Maawaam’s and then to lead the reader into those works, is no easy task. Rothacker writes from the heart, but disguises that heart in shadows. Or maybe he truly has discovered a heart in a box of papers in a shadowy closet, and he is illuminating it for us here. Either way, My Shadow Book is sharp and singular and full of mystery. -

William Morris

William Morris

Jordan A. Rothacker,And Wind Will Wash Away, Deeds Publishing, 2016.

WHAT IS BELIEF? What is it to believe in something, anything? And how far are you willing to go for that belief? Atlanta Police Detective Jonathan Wind believes in truth, but otherwise he doesn t normally have time for questions like these; he has crimes to solve and killers to catch. But this case is different. This case will challenge everything he s ever thought or known. It s also personal. It s 2003 in Atlanta, and the jewel of the Southeastern United States is sprawling far and wide with new industry and burgeoning markets. The city is at once a remnant of the Old South and an international cosmopolis. However, in And Wind Will Wash Away Atlanta isn t just a setting, she is practically a character herself, a complicated character with many layers, layers that most people traverse every day but barely notice. Jordan A. Rothacker s thrilling first novel follows Detective Wind as he peels back the layers of his beloved city, pursuing the truth behind the strange death of his mistress, Flora Ross. This pursuit leads him ever deeper into a world of sex workers, goddess worshippers, Aztec revival cults, blood sacrifices, and spontaneous human combustion. Rothacker s book takes readers into the religious underbelly of Atlanta, yet is essentially a story of people and the ways in which they struggle to relate to one another and to the world in which they live. Part mystery, part police procedural, part theological treatise, and part love story, And Wind Will Wash Away is a debut novel like no other.

An Atlanta detective, hoping to explain his mistress’s fiery death, dives into a world rife with strange religious beliefs in Rothacker’s (The Pit, and No Other Stories, 2015, etc.) unconventional thriller. Police Detective Sgt. Jonathan Wind keeps his relationship with prostitute Flora Ross a secret from everyone, including his girlfriend, Monica. So he says nothing when he recognizes a crime scene: it’s Flora’s apartment, including what appear to be her charred remains. The fire seems to have been concentrated on her body, damaging little else, so Wind’s partner, Detective Sonny Ledbetter, suggests spontaneous combustion as the cause. The detectives first question psychic Tia Maite, whom Flora saw weekly, but once it’s clear that the investigation’s going nowhere, Sonny closes the case by marking the death as accidental. Wind, however, was in love with Flora and is determined to learn more about her “spiritual pursuits”—a part of her life she kept private. He cashes in his vacation days and initiates an unofficial inquiry. After he meets Flora’s friends and interacts with a group of Goddess worshippers, he ultimately examines his own views on various religions, identifying himself as an agnostic. He also becomes sure that a Goethe-quoting albino dwarf had something to do with Flora’s demise, which is seemingly confirmed when two other men accost Wind while citing Goethe passages. Answers may finally lie within a bizarre ritual—but not necessarily the answers Wind wants. Although a traditional detective story provides the foundation of this novel’s plot, the author zeroes in on his protagonist’s inner conflict. There’s a great deal of philosophizing, including a nearly 20-page dialogue on such subjects as philosopher Immanuel Kant and theism’s limitations. Wind, though, has many nuances, and his collection of myriad Pez dispensers (all of historical figures) sometimes sparks discourse or, in one case, flashbacks. Rothacker’s prose meticulously details the action and environment with typically exquisite results: “a solid one-story brick house...corresponded to a darker, ink-rendered version beneath the pen of Jonathan Wind.” Metaphors of fire and wind are in abundance in this story, which is more concerned with understanding than resolution. Readers may be disappointed by the ending, though, which eschews a nice, clean wrap-up and fully embraces lingering doubt. A penetrating, provocative tale of a detective who psychoanalyzes as often as he investigates. - Kirkus Reviews

Rothacker’s debut novel is a rambling narrative that’s missing a plot and is instead overstuffed with dense, arcane knowledge . Atlanta Det. Sgt. Jonathan Wind lands a new case that triggers an obsessive and bewildering quest for truth. Upon investigating charred remains, Wind discovers the victim to be his mistress, Flora Ross. The cause of death: spontaneous human combustion. Disagreeing with the final verdict of “accidental death,” Wind decides to search on his own, to make sense of Flora’s death and learn who or what was really the cause. Digging deep into Atlanta’s religions, spiritualities, histories, and cultures, Wind confronts questions without answers, testing his core beliefs. Wind’s mental meanderings throw the plot out of sync, forcing readers to decipher the connections between the mystery and the tangential moments of insight into character . Wind seems hollow despite copious descriptions, flashbacks, and inner monologues; his Pez collection comes across as Rothacker’s unsuccessful attempt to give him some quirky humanity. His perspective on his own relationships remain shallow, isolating him from the other characters and, unfortunately, the reader. - Publishers Weekly

Reviews of the book:

Cleaver Magazine

As It Ought to Be

Cultured Vultures

Interviews about the book:

Cease, Cows

Great Writers Steal

The How The Why

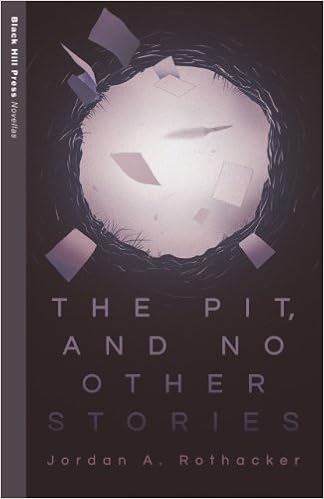

Jordan A. Rothacker,The Pit, and No Other Stories, Black Hill Press, 2015.

excerpt (pdf)

As a micro-epic The Pit has a little of everything: small town American gothic, detective fiction, spy thriller, Hollywood drama, folklore, science fiction, historical fiction, surrealism, horror gore, punk romance, and satire of American capitalism and consumerism. The Pit, and No Other Stories, might be a familiar reading experience to that of viewing the ABC television program, Lost. Many characters, different story lines, obvious points of connection, some less obvious, and many fun, stage-setting red herrings. The Pit has deep important themes about the failings of the American dream, exploitation, and objectification of humans, but it also expresses a deep veneration for storytelling, narrative, and the triumph of the human spirit through art.

“The Pit is a journey in itself, a ride with flashes of life and an ending in a place, in a world, you didn’t quite anticipate.”

Rothacker opens his novella with a vivid image of a small community in which all inhabitants eventually are hurled into, well, a pit. Just as the title suggests, the Pit is our central location. In a town, aptly named Pittsville, our narrator who remains as mysterious as the Pit itself has ventured down below in search of a watch promised to him by his grandfather upon his deathbed. The first chapter pulls the reader into a world where the inevitable is a focal point, and hints at it as something to strive towards. This is not a world of traditional burials and ash scattering; once someone has expired they are given to the Pit in a funereal fashion. After the narrator witnesses his grandfather “going over” with this promised watch still secured to his cold wrist, he sneaks out to see just how far he can reach to get back what was meant for him. As soon as he falls in, Rothacker changes the channel.We land in 1959 New York City, inside the office of a private investigator in conversation with a potential client who has no more information on his target than a nickname, The Speckled Hen. Not only have the time and place transformed, the way of talking and character’s tones are completely new. There is a hardboiled feeling added to the plot–yet a dark curiosity felt with our first character remains within this American Noir portion of the novella. This curiosity, along with the Pit, continues to rise, fall, and rebuild itself throughout the remainder of the novella.

From the P.I.’s office, we are taken on a wild ride through rainy Shanghai in 1945, fast forward to a Hollywood in 1982, drop down to Chicago in 1956, eventually falling further back in time to 1812 West Africa. There is a natural attempt to piece together the characters encountered in these various time periods and locations but Rothacker turns the corner so rapidly that the threads seem to unravel quicker than they’re sewn. This isn’t a jab at Rothacker as his chapters are packed with enough life to quickly settle you into your new environment. He’s done the research and taken the time to carefully craft the people we experience within a limited space. Many of the voices we find in The Pit are as varied as the stories we find them in. There are moments of West African Islamic Law, Mao’s takeover, and UFO sightings. Some characters return while others make a single yet impactful appearance such as an American Indian grandmother from 180 BC who begins a journey from which she may not return. However, everyone we encounter eventually meets a very similar fate that is difficult to ignore.

The Pit is an existential take on the after-life, the talk of where we go afterwards except modeled by an almost tangible place. The Pit, And No Other Stories is exactly what is presents itself as, it may seem at first as if the first six chapters serve as seven different stories all beginning with our unnamed character who falls into the Pit accidently, but slowly they begin to intertwine and unwind until we realize that there is indeed, only one story here. It is a novella full of histories and ideas. It is a story about the trials and obstacles that fall into our path as we desperately try to unearth the genius within something we deeply care for.

The Pit is a journey in it self, a ride with flashes of life and an ending in a place, in a world, you didn’t anticipate but because of Rothacker’s craftsmanship, you find yourself wholeheartedly accepting.

An Interview With Jordan Rothacker:

M: The Pit, And No Other Stories is just that, what a brilliant title, it takes place within many time periods and places, with a variety of voices. When did you stumble upon this idea? Did you fear for your reader? (Meaning, because there were so many sub plots though they all tied into a bigger portrait…)

J: Thank you. I worry that the title is cumbersome, especially when people ask, “So you wrote a novel, what’s it called?” and I tell them and then they ask, “Is it a story collection?” and I say, “No, it’s a novel. It’s The Pit, and No Other Stories.” I occasionally feared for my reader, but ultimately I trust my reader. Due to television shows like Lost or really so much in film and television and literature, people handle far more non-linear narrative than they realize. And of course it’s linear when it comes down to it. You start at the beginning of the book or film and you read and watch to the end, a straight line. William S. Burroughs used to talk about, in the 50’s and 60’s, how literature was behind visual mediums, but ultimately it is the way humans naturally tell stories, we jump all over the place, we digress, we give flashbacks and even flash forwards as we hint to the punch line of the story before we get there. In some ways I see The Pit as a more accessible or dumbed-down version of what Burroughs has done in so many novels in regards to form or what Italo Calvino had a good time playing with.

M: I’ve studied many religions myself though not to your degree or level. What influence would you say your M.A. in Religion had on this novel? What about the ideas of death within the religions you’ve studied?

J: The first novel I wrote, about ten years ago, is very much a religious novel. I actually took on the M.A. in Religion as research for the book (which is set in Atlanta and the reason why I did the MA in Georgia) and my M.A. thesis was comprised of two chapters from the book followed by an exegesis and annotations. I specialized in religion and literature in my coursework. It’s a discipline mostly coming out of Chicago and it is often said to begin with a text like The Heart of Darkness. Horror and horror in the face of the Modern is explored in this study. I also got into post-colonial studies and now combine that with romanticism in my PhD work and dissertation. Both Romanticism and Post-Colonialism are a reaction to the Enlightenment in their own ways. They seek to return a voice—and power—to those marginalized by the Enlightenment Project, so that includes the feminine, the indigenous, the non-white, the pagan, and often merely the religious, for religions are irrational, like the arts. All the “Others” of the often male, rational, white, Euro-American “Self.” While writing The Pit these thoughts certainly got in there. I thought about Burroughs a lot as I wrote this book and I often think of him in a religious context, as a mythmaker like Borges, Faulkner, Danilo Kis, and Amos Tutuola, like Hesiod, or Snorri Sturluson who wrote the Eddas. The Pit for me is a roundup of how I see different American myths. As far as a religious connection with death, I mean, it’s right there in the first chapter, The Pit is a funereal site. This weird small town gothic setting has a secret from the outside world that involves how it handles death. There is a lot of death and religion in the book, come to think of it. I think you’re on to something…

M: Reading through the novel, I couldn’t help but feel similarities within other greats that I’ve read, particularly Slaughter House Five by Vonnegut. Was this an inspiration for you? What other inspirations did you have writing this?

J: I hadn’t thought of that Vonnegut book, but without giving anything away for someone who hasn’t read The Pit yet, I can kind of see it in the “outside of time” stuff. I do like that book though; I re-read it a few years ago on the plane over on a visit to Dresden. It certainly enhanced my Dresden trip. As for other inspirations, I got to meet Margret Atwood at a reading a few years ago and I was so giddy, she’s so great. One of her books that had a great effect on me I read back when I was like 19. It was a slim collection called, Murder in the Dark. It was the perfect book for that age, too. It showed me how ok it was to break down form in a really interesting way and how much can be done with so little space. The Pit was about me returning to that youthful excitement of playing with form. For some reason in my twenties I couldn’t feel legit without writing a long naturalistic novel. That novel has yet to be published, but direct inspirations for The Pit would be Burroughs’ Cities of the Red Night and Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night A Traveler.

Romanticism and Post-Colonialism are a reaction to the Enlightenment in their own ways. They seek to return a voice—and power—to those marginalized by the Enlightenment Project, so that includes the feminine, the indigenous, the non-white, the pagan, and often merely the religious, for religions are irrational, like the arts. All the “Others” of the often male, rational, white, Euro-American “Self.” While writing The Pit these thoughts certainly got in there.

M: What about some subconscious inspirations, who are your favorite writers?

J: That’s always a tough question, but I guess it’s a bit easier than asking what my favorite book is. For that question I’d give you a list of books, most likely categorized. Of living writers I have a deep love and appreciation for William T. Vollmann. His brilliance, breadth, and proficiency is really seen in an artist, as well as the heart and social conscience he brings to his work. Reading him makes me a better writer, thinker, and person. Some times I say he is our Tolstoy and Dostoevsky wrapped up in one. He is one of the great living American writers and for skill and importance I put him up with Toni Morrison, John Edgar Wideman, Cormac McCarthy, and Thomas Pynchon of our country today. As far as other favorites go, Maggie Nelson is brilliant and the way her mind is able to harness great thoughts and deliver them with such style gets me really excited. I really love Steve Erickson and look forward to a new book from him next year and Cesar Aira blows me away. Writers of the past who get me super excited—just the first few that spring to mind—are William S. Burroughs, Anna Akhmatova, Hesiod, Ovid, Ousmane Sembene, Frantz Fanon.

M: This novel really ignites existential thought, not only through the construction but the ideas presented, ideas many people avoid. I found myself, while reading the novel, constantly thinking and venturing into deeper places. Was this the intention you wanted for your reader? Or did you envision the reader at all?

J: I love that you read it as existential. I mean I finished it after really loving what a perfect creation the first season of True Detective was. That show brought me back to reading Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, E.M. Cioran, as well as the Ligotti and Chapman that inspired it; and Vollmann had just published his gothic masterpiece, Last Stories and Other Stories. Delving into that infectious darkness, letting the pessimism wash all over you can be an engaging journey. I have to live in the world and get up every day and experience the joy and beauty of life and the people I love, but I never stop thinking about how humans are the worst species, that ultimately we are doomed. People love going to these places, the fantasy of darkness, horror movies, and literature. The arts let us tour these dark places. That’s why I think of this as an entertainment or a jive book. I’m glad it made you think and I hope it makes others think and value life in regards to death, but there are a lot of people in this world, this country and abroad, who don’t have the luxury of dabbling in darkness because they live some pretty awful situations. There’s one book that I read last year, which still haunts me deeply entitled The Corpse Exhibition, by Hassan Blasim. He is an Iraqi who now lives in Finland. The book is a collection of stories all set in contemporary war-torn Iraq. They are masterful and horrific, sometimes even surreal, and very hard to characterize. I’ve called them “war-zone gothic” for lack of a better term. Though the stories are macabre and might feel like horror writing, the thing that hits you the hardest is to know that they are based in an awful, awful reality that is part of daily life for so many people.

M: Where does death come into all of this? Does it? You seem to bring a metaphorical sense of death and sit it next to concrete examples.

J: The pit of the title is a funereal site for many who encounter it in the book. For others it involves new life in a weird way—but I’ll give no spoilers. There is a real cyclicality about life and death that flows through this book. It’s hard for me to imagine this giant deep Pit that is described in the first chapter without thinking of Ouroboros. That ancient Greek symbol loved by alchemists. It is the “tail-eater” and like many great serpents of myth—the Midgard serpent comes to mind—it is often associated with beginnings and ends. So, it is all about death but also new life, kind of how the Death card in the tarot just represents change. In some ways, and I don’t want to give too much away, but it seems like, in the book, that inside the Pit is a sort of liminal space, or a bardo, as mentioned in some Buddhist teachings. A between life and death, a place of becoming and potency, the place where the shaman or the artist goes in their practice. Hemingway was asked once what he thought about death, and he replied that it was “just another whore.” Maybe in The Pit it’s “just another trope” or “just another metaphor.”

M: You bring life to characters from many different walks of life (Black Muslims, American Indians, Chinese, even a man who sees a UFO), what sort of research was involved with this?

J: That’s the fun of a book like this and the restrictions I had upon myself: each section and plot line involved its own problem solving. Some sections required research by studying maps, digging through histories and chronologies, and some sections were just pure imagination pouring forth. I’ve taught an African Diaspora Literature class at UGA I think 20 different times over six years and yet still I went in to telling my own original slave narrative from a cautiously researched place. The device of that narrative voice in those sections worked out pretty well.

M: Why did you choose the particular backgrounds and stories you chose?

J: The whole book began for me with that first story and writing it to try my hand at this American trope of the small town gothic, a Shirley Jackson or even Mark Twain type thing. And then it became for me all about exploring all the different American tropes I like, the detective noir, the sc-fi, the southern slave narrative, a nautical/pirate story, Native American folklore, a desert roadtrip, aliens sightings over a cornfield, the tragic Hollywood fall of an actor, and even corporate business. Some are, of course, more serious than others and I spent the most labor and worry over the Native American and the African American slave portions.

M: I took note of some sentences that stood out to me, would you mind elaborating or explaining your thought behind two of them for fun?

J: Sure!

M: “With his father gone, Quentin stopped even pretending to hide how free Amadou really was, or how integral he was to the business… The African-American experience is the most important lens by which to understand America itself.” I was really intrigued by this.

J: In Steve Erickson’s last novel, These Dreams of You, a great book about race in America—so good that I even taught it despite the fact that he is white—he mentions that the American Dream belongs most to the African-American because it was betrayed for them (their ancestors) en route and yet they have stayed for generations and made America home despite the betrayal.

M: “I watched the black bile sparkle and pour from my mouth like stars from a pitcher in the sky… But to her my front was an appetizer. And she was the most frightening and real woman I’d ever met.” The imagery in of a pitcher filled with stars is very poetic.

J: That image just came to me; I think I was picturing something astrological, like a medieval drawing of Aquarius maybe. I guess I also pictured how activated charcoal would look if one were to vomit it. I’ve never tried ayahuasca actually. - Melissa Ximena Golebiowski asitoughttobe.com/2015/10/05/jordan-a-rothackers-the-pit-and-no-other-stories/

More reviews:

Athens Banner-Herald

Flagpole Magazine

Jordan A. Rothacker is a poet, novelist, and essayist living in Athens, Georgia where he earned a Masters in Religion and a PhD in Comparative Literature at the University of Georgia. Rothacker majored in Philosophy at Manhattanville College in Purchase, New York and his life has been split between Georgia and New York (where he was born); he dreams of going west. His journalism has appeared in periodicals as diverse as Vegetarian Times and International Wristwatch, while his fiction, poetry, reviews, and essays can be found in such illustrious venues as Red River Review, Dark Matter, Dead Flowers, Stone Highway Review, May Day, As It Ought to Be, The Exquisite Corpse, The Believer, Bomb Magazine, and Guernica. For book length work check out Rothacker's The Pit, and No Other Stories (Black Hill Press, 2015), and novella (or "micro-epic" as he calls it) and his first full-length novel, And Wind Will Wash Away (Deeds Publishing, 2016). His fiction can also be found in The Cost of Paper: II (2015), The Cost of Paper: III (2016), and The Cost of Paper: IV (2017), anthologies from Black Hill Press edited by William M. Brandon III. He loves sandwiches (a category in which he classifies pizza and tacos) and debating taxonomy almost as much as he loves his wife, his son, his dogs, and his cat, Whiskey.